The Iowa poet-priest who mastered haiku

Raymond Roseliep quietly became one of the most highly regarded haiku poets in the English language.

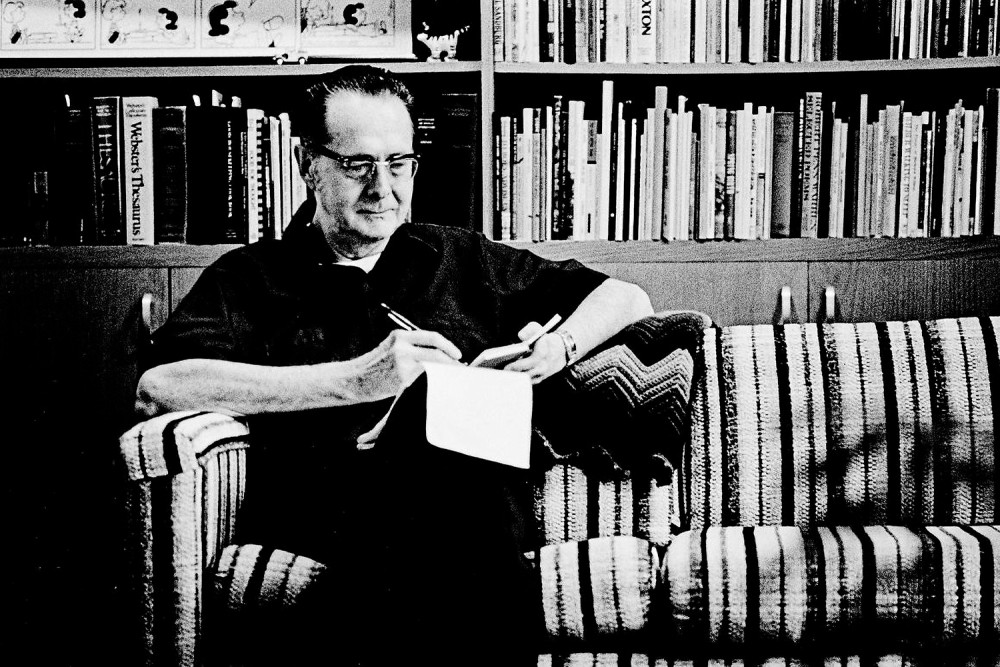

Poet and priest Raymond Roseliep (Reprinted with permission of the Telegraph Herald)

Mother, why is

Father dying on the cross

in our cornfield?

The image startles the way many of Raymond Roseliep’s images startle. His association between the figure and the cornfield underscores Ezra Pound’s poetic dictum, “Make it new.” As dark and as stark as that image is, a Roseliep haiku can also be unapologetically whimsical:

hole in my sock

letting spring

in

Roseliep was born in Farley, Iowa, in 1917 and died in 1983. A Catholic priest based in Dubuque, he was also one of the most highly regarded haiku poets in the English language.

A contemporary of poet-priests Daniel Berrigan and Thomas Merton, he lacked the attention they got. Haiku poets get less attention even than ordinary poets, if that’s possible to imagine. And he was not a social activist like Berrigan or Merton. He did not make headlines for burning draft files or writing a best-selling memoir. His sedentary life as a priest in Iowa was more distancing even than being a hermit in Kentucky.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

His link, as a priest, to poetry was classically spiritual: “When I look into the mirror of visible creation,” he told poets Mark and Ruth Doty in an interview that appears in A Roseliep Retrospective, “I see the Invisible—the world is the overflow of God’s mind—and however imperfectly, I make the things of earth and sky into poems. When I give back these gifts to Beauty’s Self and Giver, you can say I’m offering sacrifice. The incarnation of the word, then, is the reincarnation of the Word.”

To many of his readers, Roseliep’s priestly vocation was unknown. He signed his haiku simply Raymond Roseliep, and he didn’t wear vestments for author photos.

In the early ’70s, when his poems first began appearing in Modern Haiku, he informed its first editor, Kay Titus Mormino: “I do what I do deliberately—‘breaking rules.’” Roseliep didn’t begin writing haiku until he was in his 40s, when he had been a priest for years. He found another institution of rules. Haiku insists on concrete sense images, of which there are many in the priest’s poetry. It emphasizes the object itself rather than any metaphoric potential the image has, and it marks time with kigo—seasonal references, the fulcrum of traditional haiku.

Roseliep joined forces with haiku but insisted on breaking its rules. He had difficulty separating himself from metaphor, and he belittled kigo as merely symbolic. He was not shy about airing out mystical imagery:

time

is what

is still

He was criticized for this kind of move. In The Modern English Haiku, acclaimed haiku poet and editor George Swede commented: “Here is a haiku that fails to communicate because it involves abstract ideas rather than tangible things.” From a Hindu or Buddhist mystical standpoint, time would perhaps be considered a gem. But from the haiku standpoint, the mystical is made up of tangible things cradled in empty space.

Other observers of Roseliep’s work were not as dismissive of his use of the abstract. Lucien Stryk, renowned haiku translator and Zen scholar, said, “Roseliep would be appreciated as a fine haiku poet anywhere, especially in Japan. He’s the American Issa.” Haiku and long-form poet Colette Inez lauded Roseliep as “a natural resource of Iowa.” Chuck Brickley, an associate editor at Modern Haiku, called Roseliep the “John Donne of Western haiku.”

In her biography of her former teacher, Donna Bauerly begins with these words: “The central question for discovering Raymond Roseliep the man has always been simply ‘who is he?’” Roseliep, as a person, was difficult to know. Along with maintaining strictly separate identities and safeguarding his mysteries, he assumed a haiku alter ego: Sobi-Shi, which like Roseliep means “rose lover.” And he could be confrontational in approaching far more experienced and knowledgeable haiku poets and editors about haiku. One was the venerated Modern Haiku editor Robert Spiess, about whom he said in a letter to friend and fellow haiku poet Elizabeth Searle Lamb, “Robert must remember that I too have my own concept of what haiku is and what it isn’t.”

In the mid-1960s, Roseliep was humbled by a serious nervous breakdown that cost him his teaching post at Loras College in Dubuque. He spent the final 18 years of his life as chaplain to retired Franciscan sisters at Holy Family Hall in Dubuque. He became a vulnerable priest caring for vulnerable sisters, comforting them when they were sick and dying, as well as celebrating mass for them. It was work that would have resonated with Bashō, the 17th-century Zen monk who played a crucial role in haiku’s development—some of his best haiku depict life elements reduced to their bare bones.

In their interview, Mark and Ruth Doty asked Roseliep what drew him to haiku. “Well I’ve always admired reduction, brevity, Greek Anthology terseness, Emily Dickinson’s gnomic compression,” he said. “And I like the asymmetry of the three lines, the challenge of getting the right thing in the right place. I was beginning to experiment with haiku in my second book, The Small Rain, and became more and more caught up in them.”

Before Roseliep’s turn to haiku, he was a long-form poet, with rolling cadences. His first volume, The Linen Bands, was published in 1961 and has echoes of Gerard Manley Hopkins:

It would be poetry to open up

my store of feelings and play a prank

with them, by saying I was wholly drunk

as an apostle on a flowing cup

of recent grape, as James perhaps or Paul

It was not long, however, before Roseliep’s spiritual poems were stripped bare as haiku—or nearly so, as in this poem titled “Priest, to Inquirer” (haiku are traditionally untitled):

This cassock whips my

legs through the four seasons so

I’ll know who I am

“Flee,” an early work, resembles the vertically experimental offerings of Christian mystic Robert Lax:

I

run

from

me;Puff;

Step

out

of

(lord)foot

step:

soled

souledsold.

It’s the poem of a man in spiritual flight from himself. A loose, alliterative ribbon of language that is visually like a stumble.

In 1976, Roseliep published his first haiku-only volume, Flute over Walden. The poet was almost 60. His path had progressed slowly over many years. In most of his previous volumes haiku was mixed in with his long-form poems, among them many sonnets. His themes ranged from spiritual outpourings to literary musings to amorous imaginings (for which he would sometimes feel the heat of his church superiors’ disapproval):

waiting for my love.

the incurled

apple bud

Despite his range of subjects and his increasing attention to haiku, he was surely the most catholic of poets, catholic in the sense of “universal.” He published in Catholic magazines like America and the Tablet (London) but also in esteemed literary journals like Prairie Schooner and Beloit Poetry Journal, as well as in the aforementioned Modern Haiku, pinnacle of haiku periodicals.

In his work, we find mention of literary luminaries such as William Faulkner, E. E. Cummings, Flannery O’Connor, Marianne Moore, and Ezra Pound. He embarked on correspondences with Cummings and Moore, and briefly with Merton, from whom he requested an autographed picture that never came.

Bauerly recalls, “There was a kind of satisfaction for him to be in touch with particularly famous writers as well as others.” He also conducted lengthy correspondences with former students. One former student, Thomas J. Reiter, offered a critique of Roseliep’s work in his very first letter, citing, among other things, his habit of literary name-dropping. Apparently miffed, Roseliep never responded to that letter, but he kept up a correspondence with Reiter that lasted until he died.

In a poem that appeared posthumously in Modern Haiku, the poet writes:

the child called

a wrong number:

we talked all spring.

The child could have been himself. When the Dotys asked Roseliep who he saw as his audience, he answered, “Anyone! Anyone who will love me, love my poem. Love me, oh definitely. And through my words, I am loving an unseen someone in turn.”

Like Merton, Roseliep became more and more interested in Zen as he grew older. If Merton’s big influence was Japanese scholar D. T. Suzuki, Roseliep’s was Nobuo Hirasawa, his Japanese publisher and bestower of his haiku name. Roseliep took to heart Hirasawa’s teaching of mu, which in Hirasawa’s parlance boiled down to “nothing, none, empty,” Zen’s summation of the mysterious mulch of existence.

Integrating mu into his haiku led ultimately to his writing The Still Point, a weave of Zen and Catholicism that is perhaps the closest approximation of a spiritual self-portrait that we have of Roseliep.

In his introduction to the volume, he outlines its essence: “Like old Bashō’s frog, we must keep plunging. Eastern and Western frogs do, of course, and not all of them make the same sound.” The plunge of this particular frog into Zen-inspired haiku is exhilarating in part because it conforms to the poet’s fascination with our quirky manhandling of the naturally sanctified:

tape

recording

mountain silence

His haiku depict oneness, the absence of self, the far journey from “love me” to the unshadowed entity beyond duality.

a frog to sit with

and not

say a word

Along this journey, there is a crossing point from Bashō’s frog to the Eucharist. Roseliep returns to his home ground.

the Mass priest

holds up bread

the still pointholding bread

hands

are empty

Roseliep remained to the end a Catholic frog who made his own sound.