A Job who’s read Job

Poet Michael Shewmaker imagines a suffering Christian in Kilgore, Texas, with three unhelpful friends.

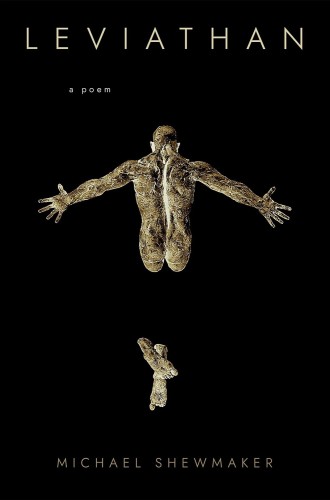

The title of this book-length poetic drama is Leviathan rather than Job, although it tells the story of J (Joiner) as he lies covered with sores on his stinking bed, in dialogue with his three unhelpful friends. His children have been killed in a horrific auto accident, his wife has left, and a storm is always brewing with thunder and funnel clouds, darkness and abandonment, and never life-giving rain. God is silent.

Leviathan is, traditionally, the king of chaos. But in scripture it is also a sign of God’s power and might. Michael Shewmaker explores this paradox. Other writers have tried it—Archibald MacLeish, for one, in his classic play, J.B. But I’m not aware of anyone else who has written of a post-incarnation Job, a Christian Job experiencing the devastation of loss, illness, loneliness, and the distance of a crucified God who might be Leviathan himself.

In the book of Job, the devil wagers with God. In Shewmaker’s book, the devil may well be God. This is poetry that questions sharply and asks for impossible answers, using stunning language which is, impossibly, both unusual and familiar.