Seeking justice for a 19th-century rape survivor

In 1894, Baylor University covered up the rape of a 14-year-old girl on campus. Two Baylor professors make the case against the university.

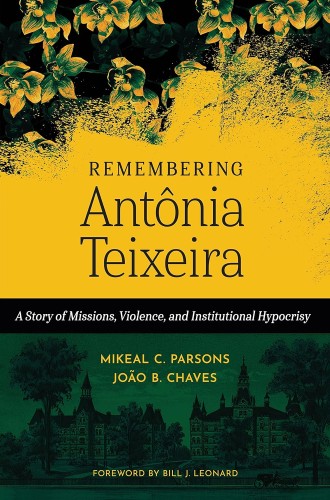

The God of Amos despised the people’s festivals and fatted animal sacrifices, and he cared not for their solemn assemblies. Much less did God care for the material wealth and abundance of Baylor University in 1894, when Steen Morris, a guest of the university president, repeatedly raped a 14-year-old student named Antônia Teixeira. The character of God has not changed since the time of the prophets, and what God wanted then is what God wants now: learn to do good, seek justice, correct oppression, bring justice to the fatherless, plead the widow’s cause. Nearly 130 years after Baylor’s disgraceful mimicry of the chastised people of the Old Testament, Mikeal C. Parsons and João B. Chaves attempt to do just that.

Remembering Antônia Teixeira reads more like a dissertation than a beach read. The authors relitigate the charges brought against Morris when Teixeira gave birth to his child, and they deliver their own damning verdict. Though the book begins with an unnecessarily long backstory about Teixeira’s father and generally appeals to a more academic readership, Parsons and Chaves succeed mightily in their efforts at retroactive condemnation. In keeping with the communal experience of justice established in the Old Testament, the authors convict not only Morris but also Baylor University and, by extension, the entire Baptist community.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Like a first-rate legal team, the authors leave no stone unturned in their case against the defendants. To make an airtight case, Parsons and Chaves chronicle the life and influence of Teixeira’s father, Antônio, a Baptist leader in Brazil, to set a precedent for the church’s propensity to rewrite unsavory history. While such exhaustive accounting might lend itself to a courtroom, it is gratuitous in this context—56 pages of a 143-page text—and bogs down the narrative. The authors might have accomplished their aim in a succinct handful of pages, especially given that Antônio played no part in his daughter’s life in Texas (let alone the case she brought against her alleged rapist), having died years earlier.

As a woman believing she had picked up a book about another woman and the trauma that countless other women have endured from time immemorial, I felt dismayed that my first encounter with the eponymous character came through her paternity. The authors take pains throughout to champion Teixeira and to acknowledge the legacy of sexual trauma so many women inherit. But the book’s opening—not to mention the authors’ choice to refer to Teixeira by her first name, which research suggests may contribute to gender bias against women—misses the sensitivity mark by a hair.

Though the authors tarry in getting to Teixeira’s narrative, when they do arrive, they spring into action. Not for a second does the reader doubt their devotion to Teixeira’s cause, or the gravity with which they undertook their ex post facto defense. Even their word choices play a role in the book’s defense of Teixeira, emphasizing her credibility as a witness: she makes her case with “specificity and nuance,” she responds to her detractors with “brilliance,” and her testimony reveals a “clear consciousness of degree.”

Parsons and Chaves also recruit contemporary experts to review case evidence, and their findings double down on the authors’ implications. Two doctors, Ann Sims and Craig Keathley, diagnose Teixeira’s injuries as “consistent with sexual assault/sexual abuse” and confirm a gestational timeline supportive of her reports. As any good defense lawyer would do, they also set about discrediting the accused and his advocates. They illustrate “attempts at intimidation” by Baylor’s president, Rufus Burleson, remark on Morris’s “sketchy memory,” and point to inconsistencies in the testimony of Georgia Burleson, Rufus’s wife, who testified in defense of Morris. My criticism above notwithstanding, the book’s mission could not be more clear.

The authors excel at seeking justice for Teixeira, and they do not stop there. The book sets Morris and his cadre in its crosshairs, but the true target is the system that empowered their duplicity: the Baptist community. In these times of mass exodus from the church and loss of faith in faith, it is vital to hold accountable the powers that be, present and past, for their sacrilege. How can anyone trust a church body that profanes its responsibility to “give justice to the weak and the fatherless; maintain the right of the afflicted and the destitute,” and “deliver [the weak and the needy] from the hand of the wicked” (Ps. 82:3–4)?

Parsons and Chaves, themselves employed by Baylor, ultimately contextualize Teixeira’s tragedy as one injustice among many, one chapter in the tome of ecclesiastical oppression. With one example after another, they detail “a host of other concerns beyond sexual scandals,” including “intentional violation of immigration legislation, missionaries using their passports to import cars and other equipment for sale on the black market, [and] aggressive support of dictatorships and explicit demonstration of racial and cultural snobbery.” The book is a call for repentance and change. In putting the church on trial, they hold up a mirror to hypocrisy and help restore the faith of the disillusioned. What could be more Christlike?

Though set largely in the past, Remembering Antônia Teixeira is a lesson for today. Teixeira was vulnerable to injustice on multiple levels, given her nationality, gender, and lack of community in Texas, and not much has changed in 130 years in terms of sexual assault. Women in today’s United States enjoy far more freedom and equality than our predecessors, but 90 percent of rape victims are female. Scripture doggedly insists upon protection of the sojourner, the fatherless, and the poor for good reason. They more than anyone are open to attack, and biblical lessons are as timeless as the brokenness of humanity. We can and should appreciate the acute restoration of justice for Teixeira, but we would do well to stave off any catharsis that lulls us into a false sense of completion. Quoting the words of a newspaper editor from the time of Morris’s trial, the authors warn, “The challenge of redemption remains: ‘Beyond the grave, Antônia Teixeira still cries out for justice. Who will answer?’”