During Holy Week, I devoted a surprising number of hours to drafting a note to place in my church’s Good Friday bulletin—a note about the Johannine passion, its anti-Jewish vitriol, and the history of violence the text carries in its train. It was hard to find the right thing to say.

I thought a lot about the Good Friday ritual, begun in Toulouse in 1020, in which a Jew was made to stand in front of the cathedral and be slapped by a Christian; about John Chrysostom’s homiletical description of Jews as beasts fit for slaughter; about the various church carvings (in the cathedral in Magdeburg, and nestled among the gargoyles of a church in Wimpfen im Tal) that depict Jews suckling on sows’ teats. I thought about Marc Chagall’s White Crucifixion and about Art Spiegelman’s Maus, a book I have long considered one of the greatest works of postwar American nonfiction—and which received renewed attention recently when Tennessee’s McMinn County School Board banned it from its curricula.

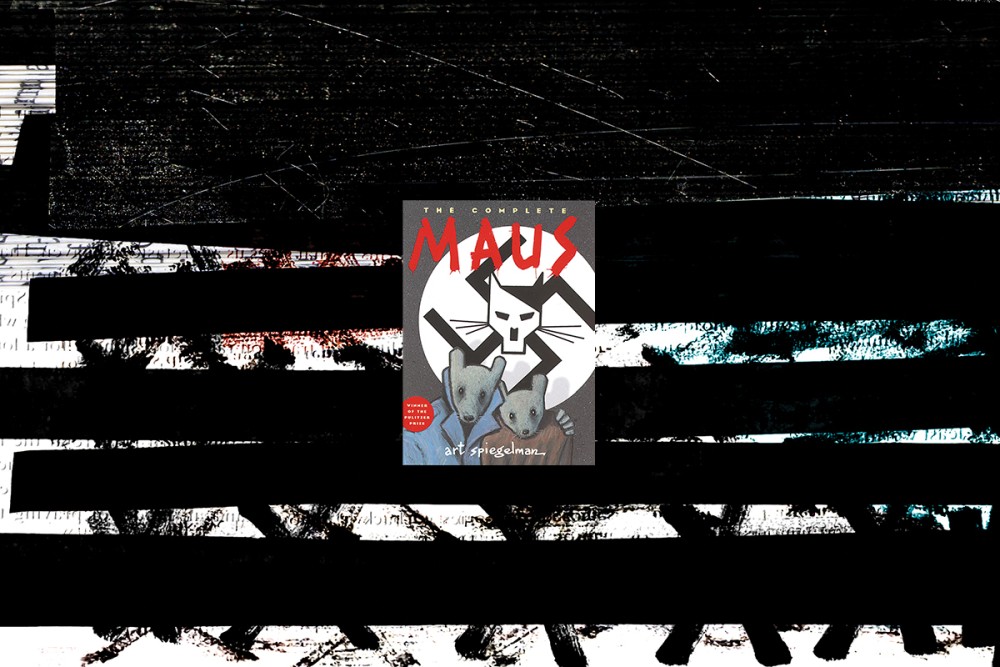

Maus is two stories at once—the story of Spiegelman’s father’s experience as a Polish Jew during the Holocaust, and the story of Spiegelman’s own experience as an artist and a son desperate to capture his father’s experience on paper. When the first volume of Maus was published in 1986, its most distinctive feature seemed to be the medium. This was before the average reader knew there was such a thing as a graphic novel, though the term had been in circulation since 1964. What was Spiegelman doing, treating such a serious topic in a medium commonly associated with the exploits of Betty and Archie and Charlie Brown?