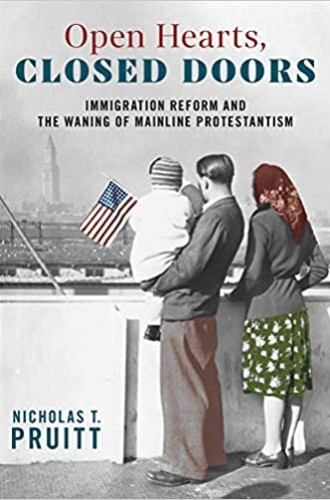

How 20th-century mainline Protestants shaped immigration policy

And how that policy shaped the 21st-century mainline church

In the standard account of immigration politics in the 20th-century United States, Protestants played a key role in pushing for the Immigration Act of 1924, which severely restricted entry by predominantly Catholic, Jewish, and Eastern Orthodox people from southern and eastern Europe. Historians sometimes depict that legislation as continuing a long-standing effort to preserve what many native-born Americans saw as the nation’s Protestant character.

Nicholas Pruitt demonstrates that this traditional narrative is at best incomplete. Open Hearts, Closed Doors details how key mainline Protestant institutions pushed for more open immigration policies in 1924 and in the four decades of subsequent debate that culminated in the Hart-Celler Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. As the book’s subtitle ominously implies, Pruitt argues further that one unintended consequence of this Protestant liberalism has been the admission of large numbers of new residents with diverse religious traditions that, in the end, contributed to the diminished influence of mainline Protestantism in American society.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Pruitt, who teaches history at Eastern Nazarene College, provides reams of evidence from religious periodicals, “home missions” reports, and testimony on pending legislation to document the transformation in attitudes of leading Protestants. For example, a Methodist bishop thundered in 1926 that “America is a Protestant nation and always will remain so,” while a later Methodist leader, in 1960, endorsed legislation that would open America’s gates to people of many religions and regions, “commensurate with our national ideals and international long term interests.”

While many leading Protestants welcomed the new “national origins” quotas for Europeans in the 1924 legislation, the Federal Council of Churches of Christ and others protested vigorously against that law’s ever more complete exclusion of Asian immigrants, this time directed against Japanese people. Former missionary Sidney Gulick led these efforts for the Federal Council, writing in the aftermath of legislative debate—in words just as applicable to today—that “the world has suddenly become very small,” with the question wide open as to “whether this is to be a glorious era of brotherhood and good-will . . . or an era of enmity, aggression and strife.” Many Protestant denominations were concerned in the 1920s that their missionary efforts in Asia would suffer because of this further extension of American racism into the international arena.

For the next 20 years, there was no political will in the nation to change the European quotas, and Protestant institutions focused on opening up cracks in that solid anti-Asian barrier. The first break came with the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, followed three years later with a law allowing the admission of a small number of Indians and Filipinos. At the time, Protestant Reformers engaged in such efforts were satisfied even with token numbers, 100 per year per nation.

Only gradually would national origins quotas be challenged, first under the pressure of displaced persons from Europe as World War II ended, then of refugees from Soviet control. Jewish and Catholic organizations in the late 1940s and 1950s pushed against discriminatory provisions, and mainline Protestant institutions joined them. From Pruitt’s evidence, Methodist Federation for Social Action representative Alson Smith was the first Protestant leader to challenge these quotas in congressional testimony, likening them in 1948 to Hitler’s odious “doctrine of racial difference.”

The widening diversity of immigrants—begun during World War II and culminating after 1965’s Hart-Celler Act—led to waning power for mainline Protestantism for three main reasons, writes Pruitt. Demographically, there was simply a greater percentage and visibility in the nation of Catholics, Jews, and, after 1965, Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists. Ideologically, mainline Protestant leaders no longer insisted that their religious traditions were the only acceptable basis for American society. And a gap widened between the attitudes of liberal Protestant leaders and those of conservative evangelicals and local churchgoers generally. Pruitt’s investigation parallels studies by David Hollinger and William Hutchison of the correlation between the growing theological and political liberalism of mainline White Protestants and their diminished status in American society.

Readers of this magazine will take special interest in Pruitt’s discussion of its role, which ranges from a 1917 editorial expressing fear of the high birth rate of “foreigners,” especially Catholics, to a 2004 analysis suggesting that “the new immigrants represent not the de-Christianization of American society but the de-Europeanization of American Christianity.” In between, the Century offered an eloquent voice against Asian exclusion, even if it took some time before the editors recognized that token national origins quotas still embodied what we now call structural racism. Two blistering 1964 editorials favoring the Hart-Celler bill focused mainly on the need to end discrimination in immigration against Asians, Africans, and Caribbean peoples. These editorials exemplify Pruitt’s themes of interconnections between immigration reform, civil rights activism, and liberal anti-communism, as well as mainline Protestantism’s abandonment of its earlier fear of Catholic immigration.

A number of errors appear in this otherwise well-researched study. Immigrants who become US citizens remain immigrants; they do not become “former immigrants,” as Pruitt labels them several times. Protestant institutions were integral to the movement which ended Chinese exclusion, but Pruitt overstates their leadership role. Among the more significant omissions is that Pruitt all but overlooks Prohibition, an obsession for many mainline Protestant institutions in the 1920s and 1930s which colored their views of Catholic and Jewish immigration.

While some readers may find Pruitt’s narrative repetitive, the story he recounts, step by step, is an important one, with clear contemporary implications. While right-wing Christian nationalism today includes anti-immigrant fervor as a bedrock principle, even a diminished liberal Protestantism can find a prophetic path through welcoming racial, ethnic, and religious diversity. Pruitt concludes by quoting Presbyterian theologian Robert McAfee Brown, who in 1962 argued that much-needed immigration reform would mean “accepting the role of tenants in a land we thought we owned, but being ‘strangers and pilgrims on earth’ is a role we should gladly embrace.”

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Immigration and the mainline.”