Climate change is a symptom of deeper planetary dysfunction

Five ideas for treating the greater disease

The rain had let up, and the fallen oak leaves shimmered in the dawn light. Just beyond us, the road to the park was closed. Fourche Creek was beyond its banks, and the water covered the pavement—an ever more familiar sight. David was there waiting, his clipboard ready with the list of possible species for the day. Bill and I joined him, noted the time, and began counting. “White-throated sparrow—three.” “Hear that, a hermit thrush over there in the privet.” “Yellow-bellied sapsucker.” “Downy woodpecker.”

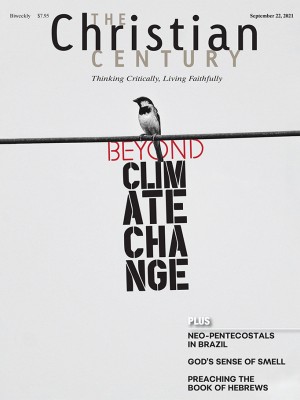

This was the beginning of the Christmas Bird Count, an annual tradition for 120 years. Teams like ours would be traveling through count circles around the country to gather data about American birds. Data from counts like these are what led scientists to deliver a startling headline in 2019: we now have 3 billion fewer birds in North America than we did before 1970, a 29 percent decline.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

For us birders, the news was disturbing but not surprising. There is an increasing sense of bio-paucity, a realization that our encounters with the natural world are impoverished. While watching birds can still yield exciting finds and abundant beauty, what I see in this part of Arkansas is only a fragment of what the Quapaw people saw when they lived here at the time of colonial encounter. Nationwide, the birds we see today are a fragment of what ornithologist Frank Chapman saw when he first proposed the Christmas Bird Count in 1900.

This decline is caused by a wide variety of factors, all born from the industrial domination of life on the planet. Habitat degradation and loss is the largest one. Many of the most threatened species are grassland birds that had a more comfortable coexistence with the smaller farms of past generations than with the megafarms that have dominated since the 1970s. Forests have suffered declines, too, both from logging and from urban sprawl. Domestic cats allowed to roam freely are another major threat to birds, one closely linked to habitat loss; they kill more than 2.6 billion birds in North America each year. Windows, cars, and collisions with industrial structures combine to kill another billion. Hanging over all of these causes is the climate crisis, with its raging wildfires, eroding shorelines, droughts, and floods—all of which harm already fragile ecosystems.

Now that I’ve brought up the term climate, it would be easy to pivot to a prescribed course of action that involves solar panels, electric cars, and enacting the Green New Deal. But while the climate crisis is a real and existential threat to the flourishing life of the planet, the problem birds face points us to a deeper crisis—one that won’t be solved by a transition to clean energy. To borrow a concept from family therapy, the climate crisis is the identified patient of our planetary dysfunction.

The identified patient is the sign of a larger problem beneath, what psychiatrist R. D. Laing calls “a wider network of extremely disturbed and disturbing patterns.” Diagnosing this patient and solving their presenting problem is important, but it won’t alleviate the underlying systems of dysfunction. Addressing the climate crisis is critical—but it won’t end the dysfunction of industrial civilization, the assault of human avarice on the diverse life of the planet.

Birders look at a concrete aspect of the whole. In some ways, this provides a better grasp of our situation than those interested only in carbon counts. It’s hard to pay attention to birds without beginning to pay attention as well to plants, insects, water, and other components in the many webs of life. I once received an email from the American Bird Conservancy urging action to stop a particular plan to develop clean energy projects on public lands because the plan bypassed environmental review and failed to address the impact on habitats. Birders know that to fix the climate crisis under the current industrial model will not end threats to the wild world we hold dear so much as alter them.

Christians worship a God who cares for the fall of each sparrow. We should be concerned that there are now far fewer sparrows in North America than in 1970, that the beautiful, orange-faced saltmarsh sparrow is vulnerable to extinction because of habitat loss from coastal development and climate-driven sea level rise. We should be concerned about the fall of a white-throated sparrow that collided with a glassy skyscraper or a song sparrow that fell victim to a loose cat, prowling the woodland edge of a new suburban neighborhood. In our concern, we should recognize the systemic pathology of industrial civilization that has brought us to a crisis with the climate. We need reconciliation with the whole, not just a solution for the identified patient.

It isn’t an either/or question. When a teenager is addicted to drugs, we can send them to rehab while also acknowledging that they might not be the source of family dysfunction. We should seek to end fossil fuel use, divest our assets from companies that promote it, and invest in clean energy. We should replace our gas guzzlers with more efficient vehicles. We should quit flying whenever we have the whim to go someplace—we should make long-distance travel rare. We should do many of the things that have been promoted as responses to our climate crisis.

But in all of this we must be under no illusions that this will mean the reconciliation of human life with the whole of creation. Solar panels on every church rooftop will not be the healing we need.

Instead, as with so many aspects of our broken world, the real healing of injustice comes through a long walk of humble mercy and the repentance that means changed hearts and lives. If the church is going to take seriously the fall of three billion birds and all that means, then we must seek the life of conversion that our discipleship demands of us.

This can be overwhelming. It is far easier to simply drive an electric car and hope Amazon figures out a better way to ship packages. But this will not move us toward the reality of God’s reign, in which each sparrow is cared for and counted. We need practices that we can begin now, in our homes and churches and communities—practices that, when enacted with grace and imagination, open the way for a different reality to begin to grow within the ruins of the world as it is.

“We will not be saved by our money, our weapons, or our technological virtuosity,” writes Eugene McCarraher. “We might be rescued by the joyful and unprofitable pursuits of love, beauty, and contemplation.” Here are five groups of practices that I hope will invite us into such love, beauty, and contemplation—and cultivate the possibility for the healing of the earth to begin in our parishes and neighborhoods.

Withdrawal. Writer Paul Kingsnorth has been one of the leading critics of what passes for environmentalism these days. In his essay “Dark Ecology,” he argues for withdrawal as a better stance than engagement in wrongheaded action. “Withdraw not with cynicism,” he writes. “Withdraw so that you can allow yourself to sit back quietly and feel, intuit, work out what is right for you and what nature might need from you. . . . Withdraw because action is not always more effective than inaction. . . . All real change starts with withdrawal.”

The call to withdraw should be a familiar one to Christians. Ours is a faith formed by wandering in the wilderness, guided by a Savior who often withdrew from the crowds to listen to God in the desert. The theology and practice of the church were formed in the wilderness experience of early monastics, who left behind the troubles of a failing empire to hear again the truth of what God was doing in the world. We need withdrawal in order to develop the reservoirs for action and to get the perspective necessary to see the right action to take.

In this time of unknowing in the face of ecological crisis, we should recover the ancient practices of silence and stillness, sabbath and solitude. Many of us have engaged with these practices in the space offered by the COVID-19 pandemic, but the pull to “return to normal” is strong. The church should be a place of resistance to the normal, a space where action is not prized over stillness, where the appropriate response is always grounded in the quiet of discernment and prayer. We need to become a people who act from the assurance of God’s love and sovereignty rather than from the anxiety of the failing powers of the world.

We also have to recognize the peril of action that is not coupled with the reservoirs of contemplation. Ivan Illich has been one of the church’s best teachers on this. In his speech “To Hell with Good Intentions,” he offered the following warning to Catholic young adults who had come to Latin America to improve the lives of the poor. It can also serve as a challenge to those of us set on “solving” the climate crisis:

I am here to suggest that you voluntarily renounce exercising the power which being an American gives you. I am here to entreat you to freely, consciously, and humbly give up the legal right you have to impose your benevolence. . . . I am here to challenge you to recognize your inability, your powerlessness, and your incapacity to do the good which you intended to do. . . . Come to look, come to climb our mountains, to enjoy our flowers. Come to study. But do not come to help.

To study, to look and pay attention, to climb mountains and enjoy flowers— these are among the key activities of our withdrawal. When we engage them, we will begin to pay attention, at least, to what we are losing. And when we do act, it will not be from the heights of abstract power but from the ground of humble grace.

Geography. There has been a growing conversation, cultivated by scholar and activist Ched Myers, about a set of disciplines called watershed discipleship. This is a way of placing our faith, incarnating it within the “basin of relations” that is our local watershed.

A watershed is an ecological space linked by a fundamental requirement of life: water. Each of us lives in a watershed, and turning our attention to the relationships born from our streams and rivers and lakes could be a way for us to begin to care for our nonhuman neighbors, providing them safe harbor.

As churches, when we begin to become disciples of our watersheds, we ask the question: Where are we? This is a question of geography but also ecology. While the placement of solar panels on a rooftop requires some knowledge of the orientation of our buildings, the questions of watershed discipleship ask us to journey much farther into the depths of our place.

Cornerstone United Methodist Church in Naples, Florida, asked the question of where they are and discovered that they are in the Corkscrew Swamp watershed, a critical area for wading birds. Their youth group began to make regular visits to a local Audubon preserve to learn about the ecosystems that make up the area. This guided the congregation into a different relationship with their place and a different way of being the presence of Christ in their community than any abstracted carbon-reducing activity would. And if they were to get solar panels, it would change the reason for such action—away from decontextualized carbon cutting and toward the love of their particular ecological neighbors.

In my Episcopal diocese, several churches have sent church members to undergo our local master naturalist training program. The aim is that these parishioners will then bring that knowledge back to the community and help guide us into living in our ecological neighborhood.

Sanctuary. The idea of sanctuary has a rich tradition in the church and has found new life in the practice of providing safe harbor for immigrants. This concept can be extended to the nonhuman world through the creation of micro refuges for our wild neighbors. Entomologist Douglas Tallamy’s books Bringing Nature Home and Nature’s Best Hope are compelling guides to how we can transform our human landscapes to become better hosts for wildlife. Fundamental to this is replanting our landscapes with native plants that host diverse insect populations. (Many insects, especially caterpillars, cannot eat non-native plants.) Insects are foundational to our ecosystems, and much of the loss of wildlife such as birds is a result of the drastic loss of insects.

What if churches ripped out their lawns and parking lots, replanting their landscapes with native plants? Not only would these plants be more resilient to the climatic changes upon us, they would also provide habitat and food to creatures squeezed by development and the pressures of our changing climate. (The Audubon Society’s Plants for Birds resource includes a helpful tool for finding beneficial native plants for your zip code.)

The provision of refuges for the creatures that live in our watersheds can extend well beyond our churchyards. Coffee is an unofficial sacrament in most churches, and with the right coffee we could be preserving the lives of many species, including the neotropical birds that nest in North America during the summer and spend their winters in the coffee-growing regions of Latin America. When coffee is grown under native shade trees it preserves the multistory structures of tropical forests and provides important habitat. The Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center has a certified bird-friendly coffee program, with a number of roasters to choose from. What if churches in North America partnered with churches in Latin America to preserve the habitat of the birds they share? It could be an important ecclesial and ecological connection.

Skill sharing. Our church communities have the opportunity to do more than simply preserve habitats or become refuges for the wildlife of our watersheds. We can also get our hands dirty by becoming centers where we learn practices and skills for the world ahead of us.

“We must achieve the character and acquire the skills to live much poorer than we do,” writes Wendell Berry. “We must waste less. We must do more for ourselves and each other.” Our churches could be places to acquire both the character and the practical skills for our time of ecological crisis. Such skill learning is a wonderful opportunity for intergenerational exchange. I was once a part of a series of workshops on canning vegetables that was filled with young people and taught by a woman in her 80s with a lifetime of practice. As we recover the arts of mending and repairing, of growing and cooking, we can turn again to the wisdom of our elders.

Skill sharing can also be a wonderful opportunity for outreach. In many communities skill swaps are regular events, and churches could easily become sites for local skill swaps that need space. Another concept along these lines is the old idea of the grange. Granges were once community centers in agricultural places where people could share resources and tools. What if churches could be granges that provide tools and resources for communities transitioning into a more sustainable way of life?

The church itself also has the potential to share and cultivate soft skills that will be critical for the age of ecological crisis into which we are moving. In a world where food may be scarce and tribalism rampant, the church should be a place that preserves the skills of humane conversation and community. As C. Christopher Smith writes in How the Body of Christ Talks, “conversation is at the very heart of our being, as humans created in the image of the Triune God, who exists as a conversational community.” Churches, which embody and teach this truth, should be places where substantive and critical conversation takes place in a context guided by silence and listening, open always to the insight of the other. Such careful conversation, built in the context of our common life, could offer real hope and help to a world that does not know how to be together but will need to be united in order to maintain the goods of humane and creaturely life into the future.

Mercy. A world in the midst of ecological crisis is a world in need of mercy and compassion. The tradition of the corporal works of mercy, based on Matthew 25, offers an important set of actions for any church that hopes to respond faithfully to its neighbors, human and otherwise, in a time of climate chaos. The work of feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, clothing the naked, caring for the sick, housing the homeless, visiting the prisoner, and burying the dead should be engaged with a renewed imagination as we move into the time now upon us.

What, for instance, does offering water mean in a time of drought and polluted streams? What does housing the homeless mean for both climate refugees and wild creatures who are left without habitat? These are questions we should ask as we engage in the works of mercy in a time of planetary crisis. The Ekklesia Project has created a helpful resource (which I coauthored) to begin this work with its pamphlet “Embodying Care: The Works of Mercy and Care of Creation.”

The years ahead will be critical to the future of the life we have known on our planet. We need energy transitions, infrastructure changes, and much of what has become the standard response to the climate crisis. But that crisis is only a symptom of a disease that goes to the heart of the human relationship with creation. We must cut all of the carbon we can as quickly as we can. But we should seek to do so within a frame of healing the whole, of exorcising the demons of our dominion made manifest in industrial civilization. We should not build windmills at the expense of migrating birds. We should not trade carbon pollution for lithium waste. The world should suffer no more from human life beyond its creaturely limits.

The church has a unique and important role to play in the cultivation of a different way of living as creatures within the whole of creation. Such work carried out humbly, on a humane scale, can be meaningful and rich, even if it does not solve all the problems we’ve wrought. The world, after all, is God’s to save, and our own attempts to play God have been part of our problem. Our call is to love and care for our neighbors within our limits. This is work enough for those who engage it fully—and for some corners of creation, it can make all the difference.

A few weeks after the Christmas Bird Count that wet winter, I went birding with Bill from my bird count team. Bill is in his 80s and has been birding since he was a teen. He has seen the decline of many species, the changing range maps of others; he has witnessed the impoverishment of the natural world as well as its grace.

That day we hoped to find a whooping crane that had been spotted at a nearby wildlife refuge. Whooping cranes once numbered in the tens of thousands in this country, but through hunting and habitat loss their population had dropped to about 22 birds by 1941. Through the care and love of a few people and the community support to make it possible, as of 2011 there were more than 400 whooping cranes in the wild.

In the midst of the refuge, we found the bird as promised—elegant with white plumes and long legs, towering over the nearby great blue herons. Here was a bird that almost became extinct, wading in a pond beside a gravel road, witness to another way for humans to live in the world. In seeing it I had some hope that even in the face of ecological crisis there are things we can do, actions we can take that will help heal the damage we have done. We can, if we come together, save one species, one fragment of woodland, one place from the march of the machine. We can learn to take care of each other, even into our deaths. We can welcome strangers and share what we have with those in need. These are practices in which the church has long been engaged, practices that must be renewed as we move with the hope of the resurrection into this world gripped by death and its powers.