Ivan the gorilla’s smart-mouthed sidekick gets his own sequel

Katherine Applegate’s books for children are just as engaging for grown-ups.

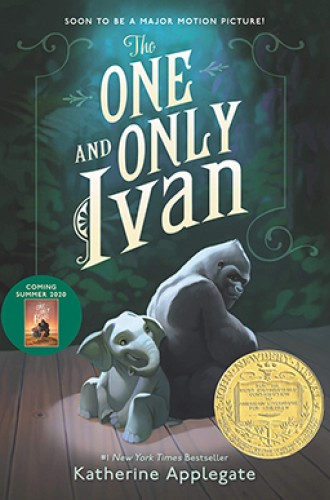

I recently asked my 11-year-old grandson, Nicholas, who is a serious reader, what his favorite book is. Without hesitation, he said The One and Only Ivan. Ivan, who is a gorilla, has “real emotions,” he explained. When I pressed for more, he paused a moment, then added, “Ivan knows how it feels when a friend dies.” Katherine Applegate may not be America’s greatest living writer, but countless children and parents would say that she is one of them. She has authored or coauthored more than 150 best-selling children’s books. Ivan alone sold more than half a million copies within a year of its publication. The following year it won the Newbery Medal, and since then it has chalked up another half million sales. This summer, Disney+ released a full-length movie version.

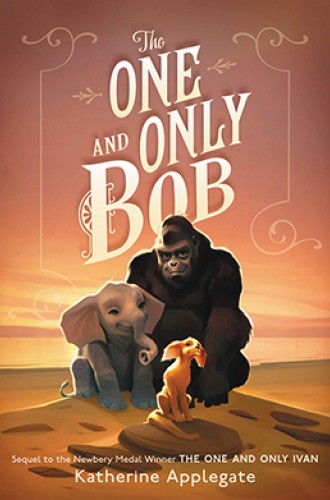

Now Applegate has published a sequel, The One and Only Bob, which has already started to win the kind of acclaim bestowed on Ivan.

Ivan is told through the eyes of a fictional gorilla whose life parallels that of an actual gorilla. The real Ivan, born in Africa, “spent the first 27 years of his life in a shopping mall in Washington State,” Applegate notes. In 1994, Ivan was moved to a wildlife preserve, where he enjoyed good care and relative freedom until his death in 2012.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Bob, in turn, is told through the eyes of a character based on Applegate’s dog, a “sassy little guy” named Stan who spends hours sitting on her lap as she writes, bestowing inspiration and bad breath.

The books feature a mostly overlapping cast of characters. There’s Ivan, a 400-pound silverback who would have been king of the jungle if big-game hunters hadn’t killed his parents and kidnapped him to sell in America. Locked in a glass cage at the Big Top Mall, Ivan spends his days watching a flickering black-and-white TV, dining on bananas, munching an occasional insect, and drawing with crayons on scraps of paper that his human pal, ten-year-old Julia, slips him.

Stella, an elderly elephant, occupies the cage next door. Until coming to the mall, she lived most of her long life as a performer in a traveling circus. The drill was simple: stand on a stool while a little dog runs up and down on your back. Stella longs for freedom from the ropes that still strangle her ankles.

Ruby, a young elephant, just starting to learn circus stunts, joins Ivan and Stella at the mall. Her naïveté about the harsh discipline ahead prompts her friends to try to dream up a way to get her out.

Finally, there is Bob, a small mutt with an attitude. In the first volume, Bob serves as a smart-mouthed sidekick for Ivan. In the second, he becomes the leading actor. One sunny day, without warning, Bob finds himself in the front end of a tornado. In the resulting mayhem, he discovers emotional resources he never knew he had.

The books make a nice package. Bob picks up where Ivan leaves off. Ivan’s pace is leisurely, reflective, and very funny. Bob starts slow but soon becomes a page-turner, and it is also very funny. (“Peeing without a potential audience is like talking to yourself.”) Yet Bob is deeper, deftly hinting at what a second chance in life might look like.

Ivan fancies “colorful tales with black beginnings and stormy middles and cloudless blue-sky endings.” So it is not surprising that both books offer complex narratives with unexpected twists, memorable outcomes, and characters marked by remarkably nuanced feelings. Both consist of taut, versified sentences, usually three or four to a page. Yet the brevity is deceptive. Applegate wastes no words.

Like all children’s classics—one thinks especially of Charlotte’s Web—Ivan and Bob can be read at multiple levels. On one level, these books are sure to grip the imaginations of eight- to 12-year-old kids. On another, they will engage adults (particularly older ones, I suspect, who are prone to look back and wonder what the journey has been all about). Multiple themes flow through both volumes, including the joys of a life well lived, the sorrows of a life squandered, the power of art to turn imagination into reality, and the gnawing pain of loneliness.

There are several other significant recurring themes. Inexplicable cruelty, encapsulated in the way humans treat animals, may be the point that children will notice first. To be sure, both Ivan and Bob are sometimes pleasantly surprised by humans who are willing to save animals from danger. But more often they are not. Ivan wonders about a “cluttered, musty store” near his cage. “They sell an ashtray there. It is made from the hand of a gorilla.” Bob notes that gorillas and elephants have no natural predators. “So humans step in to fill the void.”

The absurdity of racial stereotypes arises often, and in this sense Ivan isn’t innocent. Chimps are ridiculous—there really is no excuse for them, he says. Deep down, however, he knows they are all part of the same primate family (as is little Julia). The differences are superficial. Bob explains it well. He would just as soon play with a Dalmatian with its spots, or a Shar-Pei with its wrinkles, as with any other dog. Why not? “Constantly seeing differences where none exist. All those things like skin color? Dogs could care less.”

Ivan and Bob notice that life is filled with ambiguities, like the one revealed by cowboy movies. “In a Western, you can tell who the good guys are and who the bad guys are, and the good guys always win,” Ivan observes. “Bob says Westerns are nothing like real life.”

Another recurring theme is forgiveness. This theme emerges most poignantly in a conversation between Bob and his sister, Boss. A fugitive of the streets, Boss bares her soul. “All I know is, I’ve done lots of bad stuff in my life, Bob. I’ve had to forgive myself plenty, just, you know, to get through the day. . . . And I figure if I’m going to forgive myself, I’d better be ready to cut everyone else some slack, too.”

The sweetness of first love isn’t exactly a recurring theme, but when it appears it is so exquisite that many readers are likely to remember it. Ivan meets Kinyani at the zoo. “I admire her intact canines from afar,” he shyly admits. “She is faster than I am, spry and probably smarter, although I am twice her size and that, too, is important. She is terrifying. And beautiful, like a painting that moves.”

Figuring out how to win Kinyani’s affection isn’t easy. “Make eye contact. Show your form. Strut. Grunt. Throw a stick. Grunt some more. Make some moves.” Ivan concludes that “romance is hard work.” But the pain is worth the effort. After all, “is there anything sweeter than the touch of another as she pulls a dead bug from your fur?”

Applegate’s genius lies in her ability to use reversal as a lens for seeing the world in new and more truthful ways. We don’t expect an insect to be a dessert, or an intact canine tooth to be alluring, or a Dalmatian’s spot to be a stab of conscience. Even laugh-out-loud humor, which pops up everywhere, opens a pause, another twist of the lens.

But then readers of the Century should not be surprised by the transformative power of reversal, simply told, without ado. More than once, incongruities scooped from the soil of daily experience fell from the lips of a carpenter from Galilee.