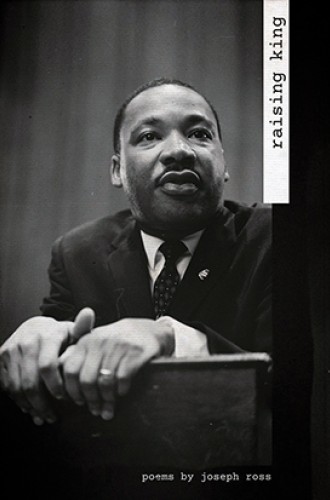

Dr. King’s voice in verse

Joseph Ross’s poems are an elegy for the civil rights movement’s martyrs.

Raising King is hauntingly prophetic. Published this month, it comes after the horrific killing of George Floyd, marches across the country protesting police brutality, assaults on the Black Lives Matter movement, billy-clubbing paramilitary police’s abrogation of civil rights, the continual undermining of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the tyranny of Lafayette Square, and the deaths of iconic civil rights leaders John Lewis, Joseph Lowery, and C. T. Vivian. Many of today’s civil rights struggles look back to the 1950s and ’60s—an era that Joseph Ross writes about so tellingly, so powerfully.

Echoing Maya Angelou’s and Michelle Obama’s affirmations, the book’s final poem declares of Martin Luther King Jr.: “Using time with love / is our revolution. // This is how we raise him. / This is how // we rise.” At their best, Ross’s poems raise King’s soul and spirit to give us the sustenance of hope that America sorely needs now.

The book’s 78 poems are divided into three sections, each based on one of King’s political autobiographies: Stride toward Freedom (1958), by the 28-year-old pastor writing about the Montgomery bus boycott; Why We Can’t Wait (1964), which bewails the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing and other violence; and Where Do We Go from Here? (1967), written during the last year of King’s life. Each poem carries a sentence or two from one of these books as an epigraph.