Majority of White Christians see no pattern in killings

Two days before Rusten Sheskey, a White police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin, fired seven shots into the back of Jacob Blake, a Black man, at close range while three of Blake’s young children watched, the Public Religion Research Institute published its latest report on racism and police brutality.

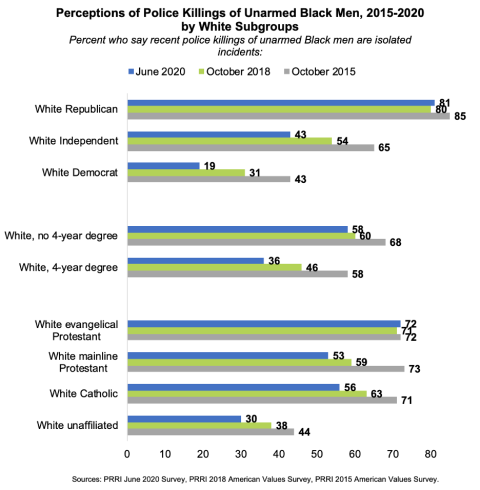

During a summer punctuated by White police officers gunning down Black body after Black body, PRRI found that most White Christians—across denominations—continued to see such shootings as isolated incidents.

Based on polling done in June, the majority of White mainline Protestants (53 percent), White Catholics (56 percent), and White evangelicals (72 percent) believe that when the police kill a Black man, it is not representative of a pattern in the way law enforcement treats Black people.