The United Methodist meeting offered no clear way forward. What now?

The UMC, a global church, prides itself on its democratic and decentralized polity. All this shapes its response to LGBTQ couples and clergy.

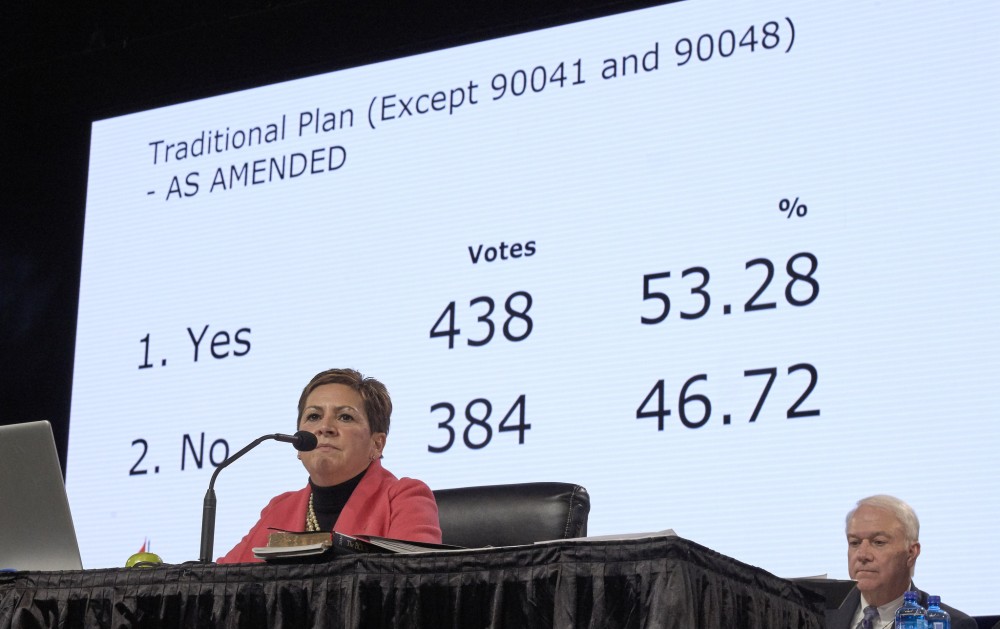

The special General Conference of the United Methodist Church in February was more of a pivot point than the finale in the denomination’s long debate about the inclusion of LGBTQ persons in the life of congregations and ordained leadership. The assembly adopted by a 438–384 vote the so-called Traditional Plan, which excludes LGBTQ persons from ordained leadership and prohibits ministers from officiating at same-sex marriages. But the plan’s major enforcement provisions were ruled unconstitutional by the church’s Judicial Council, making the results of the vote far from decisive. Furthermore, the UMC has another general conference looming in May 2020 at which this year’s vote could be overturned and another approach could emerge.

The UMC prides itself on its democratic, decentralized structure, and its deliberations on this issue have revealed the several interworking dimensions of UMC governance. The first of the church’s three largest decision-making bodies is the Council of Bishops, made up of all UMC bishops throughout the world. The church’s legislative body is the General Conference, which meets every four years and is made up of elected delegates (half clergy, half lay) from each regional body (what Methodists call an annual conference). A third body, the Judicial Council, determines the constitutionality of matters referred to it by the COB and the GC.

The debate is also shaped by the fact that the UMC is a global church. It includes not only the 54 annual conferences in the United States—clustered into five jurisdictions—with a total of about 7 million members, but also 75 conferences—clustered into seven bodies known as “central conferences”—in Europe, Eurasia, the Philippines, and Africa, with about 5.7 million members. Many General Conference delegates come from countries where being gay is illegal or where gays are persecuted. In the United States, support for LGBTQ inclusion has gained steadily since 2014, when the Pew Research study found that 60 percent of United Methodists in the country supported same-sex marriage.