What wondrous poems are these

James Crews's poetry is at once ecstatic, skeptical, and hopeful.

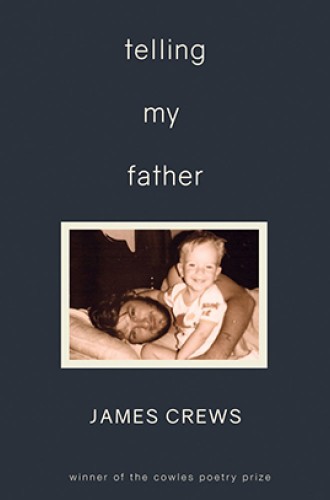

Occasionally, I read a debut poetry book and want to grab everyone I know and tell them to read it, too. Vermont poet James Crews’s collection is one such book. These poems react to the world both ecstatically and skeptically, revealing a longing for permanence—of life, of love—in a life marked by transience. The book skips back and forth between spirit and body, eternity and the ever-shifting nature of time and the moment, dwelling on relationships—especially with the poet’s father, but also with his husband, former lovers, God, and the earth. Readers who enjoy the work of Richard Wilbur, Robert Frost, John Donne, Ted Kooser, Mary Oliver, and W. H. Auden will find a kindred voice in Crews’s work.

Crews’s touchstone poem, “Human Being,” introduces themes of lightness and heaviness, contained within the “human” and “being” aspects of a person:

The human part of us

wants and needs and breaks,

but the being part sees

beyond the body’s aching

joints and joyful noises

to the open road ahead.

The energy of the sounds in these lines—the repetition of vowels and consonants in aching and breaks, in joints and joyful—typifies Crews’s pleasurable play with language throughout the collection. Thematically, the poem posits the existence of the divine in “being,” in “the source” and “the light,” a divine presence toward which humans must trudge “forward, step by step / in our heavy boots.”

Throughout the collection, divinity appears slantwise and symbolically: in “fine mist” (“Chore”), in the sky (“What Goes On”), in the smoke of marijuana (“God Bud”), and in all the tiny floating bits of the world (“God Particles”). The challenge for us all is to find eternity, despite our doubts.

Among Crews’s many gorgeous examinations of divine purpose and death, one of my favorites is “Midnight Snow,” in which the narrator watches an otter peacefully drifting into his den as the animal “floats on a faith / we wish could carry us the same.” After watching the otter’s placid acceptance of the current, the speaker wishes

to be that slick body

sliding into the lake without so much

as a shiver, no doubt about where

I’m going or how to get there.

The repeated “s” and “I” sounds of the line briefly transmute the reader into the passive otter, meditatively allowing the currents of our destiny to move us forward through life into the warm and “deep” sleep of the den without useless splashing.

Similarly, Crews holds out hope for God’s presence in “For Those Weary of Prayer,” an absolutely magical poem that begins with fireflies, cicadas, and children playing in sprinklers and ends with a profound question:

Aren’t you always

calling the name of what you love most

back to you, over and over, holding

the door open and pleading, Please don’t

make me ask again—and then asking again

until he comes?

Crews’s evocation of a parent calling his or her child to come inside at night ingeniously undercuts the familiar trope of God as Father, turning God into the impatient but ultimately faithful child who will return when called in love.

Occasionally, though, Crews’s poetry echoes John Donne’s impatience with God’s gentleness, as in the ending of “God Bud,” a poem about smoking marijuana: “when God / enters me, I thought, I want it to burn.” Crews’s poems mix a placid tone with an edgier, harsher complement.

Much of the roughness of the poems stems from Crews’s examination of masculinity, mainly in poems about his father. Masculinity in the poems is often associated with the tangible, specifically with manual labor. What do men do in these poems? They work hard. They “hack,” “dig,” and “chip” at taproots (“Chore”). They learn the “language of manhood”: “Phillips head, needle-nose, catalytic converter.” They fix cars, hunt, and mow the lawn, and their faces “scratch” with “stubble” (“Halfway-Heaven”). The men in the poems—working, drinking, threatening a gay man with a switch knife—aren’t caricatures. Yes, they pull up their “green- / striped tube socks” (one of my favorite little images in the book) and mow the lawn, like thousands of men do in the summer. They can be tough, and even mean, but they also repair what needs to be repaired, and they’re capable of profound love.

In “Telling My Father,” the speaker comes out to his father through silence (another theme in the book), not announcing that he’s gay but merely keeping on his eyeliner. Rather than with anger, the speaker’s father responds with a smile, rubs his son’s back, and leaves him a glass of orange juice, a simple object turned into radiant peace offering. And when the father is dying, the speaker cares for him tenderly, feeding him nutritious food, massaging him, and kissing his dead body. Even after death, the father returns to the son during a car accident and anchors him to life, holding his damaged body together until the paramedics return and the father can disappear back into death.

There is so much love in this book—love between parents, love for the world, romantic love. Another of the book’s most wondrous poems, “Waiting for Love,” compares waiting for love to hoarding honey, ending with the glorious lines

pry off the lid

of every jar and scoop what is now

crystallized, shining in his hands, somehow

still delicious after all that time.

Love is delicious. It appears in the form of a lover’s arm heavy in bed, watching a group of elk, or biting into a juicy apple. Crews’s poems, even when exploring grief, never lose that essential wonder and amazement at the world that comprise the best of poetry. Reading his poems is a joyful experience, and one that speaks deeply to what is deepest in the reader: the need to belong here, in the dazzling moment, and in whatever transcends the moment.

Crews’s poems don’t just speak to those well versed in poetry, but to all thoughtful readers—and to all of us who wonder about the purpose of this maddening, thrilling life. As he concludes in “As You Label It, So It Appears to You,”

Call it holy,

holy is what you will taste.