11 adverbs for good preaching

The best preachers, says Russell Mitman, preach liturgically, eschatologically, multi-sensorily, and eight more ways that end in -ly.

United Church of Christ minister F. Russell Mitman transfigures the pulpit with his conviction that preaching is more than a seated activity within the walls of the local church. Because “there is one Word, Jesus Christ, who is proclaimed and who is present in an assembly through the Holy Spirit in the actions of Word and Sacrament,” preaching is an event that can only be understood in relationship to the fullness of the liturgy, the presence of the worshiping body, and the illumination of the Spirit.

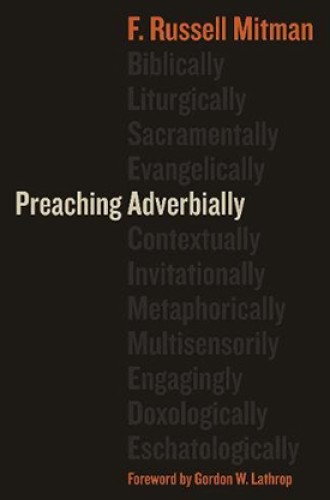

In other words, preaching is more than a noun. It’s a verb. Mitman also uses gospel as a verb, claiming that a person who proclaims the good news of Jesus Christ “gospels.” Because “preaching is more than a sermon and is the intent of the whole liturgical action,” Mitman writes, “this action is best captured in adverbs.” The preacher who gospels is one who preaches biblically, liturgically, sacramentally, evangelically, contextually, invitationally, metaphorically, multisensorily, engagingly, doxologically, and eschatologically. Mitman devotes a chapter to each of these adverbs, illuminating 11 ways preachers can enhance their work.

Mitman portrays preaching most dynamically in the chapters that explore preaching engagingly and doxologically. Here he intentionally removes preaching from a stagnant script, opening it up as a platform for communication between the Holy Spirit, the preacher, and the assembled body of worshipers. Not only is preaching a verb, it’s a conversation that takes place within the liturgy. On preaching doxologically, Mitman notes that “assemblies easily can detect whether the various elements of the service—including the sermon—blend harmoniously or, on the other hand, worshipers are being forced into a discordant maze.” Drawing on a traditional metaphor for the church, Mitman claims that the many parts of a worship service are akin to the different parts of the body of Christ. Without all components in harmony, the liturgy is lacking.

Mitman is consistent in his claim that preaching must come from a place of authenticity. The wise preacher offers a sermon not simply for the sermon’s sake but rather to create a space for the spoken scripture “to gospel.” This type of preaching is “an art of engaging the assembly: imaginatively, inclusively, believably, carefully, and gracefully.” Healthy personal relationships can’t be founded on conversations that are forced. Likewise, a forced sermon is less able to allow space for the Holy Spirit’s action among the listeners and the preacher. Authentic preaching, in this view, transfigures the pulpit into a congregationally shared space.

Preaching metaphorically encompasses only one chapter explicitly, but it is evident in each chapter. Mitman continually draws on the imagery of the Old Testament, the New Testament, liturgical practices ancient and modern, and even the occasional heady theologian to create a rich metaphorical world. In this world, the sermon is not merely the reading of a text or the giving of a speech. It is a thousand pictures, histories, and voices being collected into one and ordered through the triune God.

Although Mitman asserts strong opinions about what God is doing through preaching, he does so with enough humility to keep his arguments from coming across as a prescription for all preachers. It’s primarily the Spirit who is at work in any preaching act. He writes:

It took some deep soul searching for me to be able to affirm to myself that mortal words somehow by sacramental grace through the Holy Spirit can become the word of God for those who have ears to hear, and even, that God will give ears to those who claim they have no ears or even do not want ears to hear what God is saying.

As the early chapters demonstrate, the book sits solidly within a liturgical and sacramental understanding of the church. Yet Mitman is fairly open in his interpretation of those characteristics. He critiques some worship practices and liturgical styles without labeling any particular denomination right or wrong.

As he investigates the adverbs that encompass the journey from scripture to pulpit to listeners, Mitman includes stories from his own life as a preacher and quotations from sermons he has preached. But he also addresses a variety of topics beyond preaching, including social media, hymnody, theological history, the meaning of evangelism (as opposed to proselytizing), and personal stories of people who found radical welcome in the church. Imagination, mystery, art, and relationship are also important to the author, as they distinguish the living Word from something lifeless on the page. This multifaceted understanding of how to gospel offers both preachers and hearers new ways to taste and see God’s presence in the act and art of the sermon.