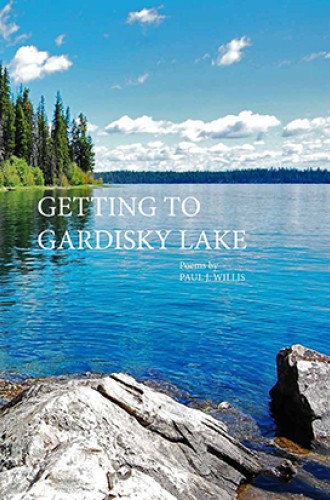

Not surprisingly, this book of poems by outdoorsman Paul Willis encourages us to dive deeply into nature. However, it is—even more so—a book about getting somewhere: getting to the lake, getting past obstacles and excuses, getting through day-to-day obligations to where we most want to be. Or not getting there, not arriving yet at that other world that calls us to “the incantation of incense cedar and sugar pine,” to “more there / than you have ever been in your life . . . / To join them, to take root.”

The opening section, “Gatherings,” focuses on epiphany. In the gatherings of this world, the narrator exclaims after watching a softball game from the sidelines, “I could have played . . . . There is room for me in this world.” In the poet’s memories of childhood and young loves and in his hikes across mountains and the rough terrain of aging, there is space for each reader to ponder, explore, and say: “Me, too. There is room for me.”

Other epiphanies combine the spiritual and the physical:

It happens in the slow light

of December dawn, the waking

of clouds, the acknowledgment

of a long presence. The roadgathers under your feet, the roughness

of it felt, not seen. Too cold

for snakes, but a palm frond

blown to the ground can rakeyour soles and spear your toes

straight through with thorns.

Crucifixion happens daily, just

like that, on the heels of triumphal entry.

Willis also examines the public roles of political servant—“above the creaking pews of the public”—and professor, offering the type of advice that makes us laugh while encouraging us to look inward. Those in academia will recognize too well the truths and tensions in “The Assistant Professor Tells All,” “Guest Lecture,” “Course Schedule,” and “A Critical Difficulty.” But Willis gets directly to the experience of reading in “Introduction to Literature”: “For your exam, sleep in the rain forest / seven years, and when you wake, / trace the Amazon to its roots / in the fluted faces of the Andes.”

Experiencing life is what Willis’s poems are most about. In a poem reminiscent of Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” the narrator also would prefer to linger but instead moves quickly toward obligation. “I had somewhere to go / at the time . . . so I did not take what the canyon offered. / . . . I never went in. That’s why / I’m telling you this, so you can go first.” In another poem, appropriately titled “Idling for One Minute Only,” the poet counters, “me, / standing in the new warmth // of the winter sun, watching // the first green tips of grass emerge / from the dampness of the ground.”

One of my favorite poems, “Harvester Island,” describes boys burning garbage on “an island off an island / off the rest of Alaska”:

Fishing boats nuzzle their nets,

and the sky is the gray of a late-August morning,

the sort of morning you might think

of going back to school again,

whether you have a school to go back to or not.Before you can decide, however,

the smoke is gone and only the kelp

is left as witness. That, and an otter

just offshore, backstroking into the present.

This poem connects the author’s various worlds and points toward the book’s final section, “Latitudes,” where “summer is as sure as the moon / that ripens on the rim of the sky” and “Green wears a ponytail that dangles / like a sheaf of ferns.” Here “Fog has a way / of holding us in the immediate present, / which suddenly includes the past. / This cow, for instance, chewing / the cud, ruminating infinite space.”

In poems so grounded in place that we can smell both bloom and bark, the poet guides us along paths and through valleys. He shows us a suckerfish “open-mouthed in dead surprise.” Most importantly, he shows us ourselves. Willis brings us, time and again, to the epiphany we first encountered in the opening poem: we, too, can be part of this world.

The book’s last poem finally takes us on that trail toward Gardisky Lake. This is where we’ve been headed all along. “And we step forward / as if we are hardly allowed, / off the map, into the world.” Yes, yes we do.