On Luther and his lies

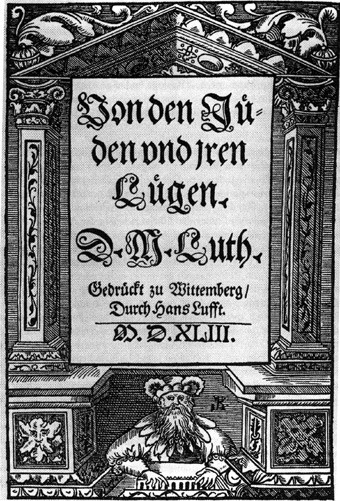

As the Reformation's 500th anniversary nears, Christians are contending with Luther's violently anti-Jewish writings.

When Martin Luther posted his 95 Theses in Wittenberg, he set in motion a revolution which transformed Christianity, Europe, and eventually the world. Jews and Judaism were a relatively minor detail of the Reformation, but Luther’s virulent anti-Judaism and anti-Semitism—a term first used in the 19th century—left a legacy that would be cynically championed by the Nazi cause and religiously heralded by some Christian leaders in the 20th century as genocide was perpetrated against the Jewish people.

There is hope in this sad story because Lutherans and other Christians confronted their anti-Jewish past during the second half of the 20th century. But before celebrating that change of heart, the first 400 years of Luther’s legacy must be remembered. The retelling of that story is not simply an academic exercise. It represents a commitment by Jews, Christians, and others to acknowledge that those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Even when we study history, we humans sometimes, perhaps even quite often, repeat it. Unfortunately, the Shoah was not the final genocide of human history. And today we see almost every day—including recently in the United States—how the venom of xenophobia, racism, and hatred inevitably leads to violence.

Luther initially believed that kindness toward Jews was the right path, if only for the purpose of enlightening them and opening their eyes to Christianity. As a professor of Old Testament, he believed that Jews could be taught the proper meaning of certain Hebrew Bible verses prophesying Jesus’ life, messianic mandate, and New Covenant, thereby leading to their conversion. This period in Luther’s early fame is represented by his essay “That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew” (1523). Both the title and intermittent points of the tract foreshadowed some elements of 20th-century Christian outreach to and reconciliation with Jews. For example, Luther writes, “We gentiles are relatives by marriage and strangers, while they [the Jews] are of the same blood, cousins and brothers of our Lord” (I rely here as elsewhere on Thomas Kaufmann’s Luther’s Jews: A Journey into Anti-Semitism).