The military doesn't own the American flag

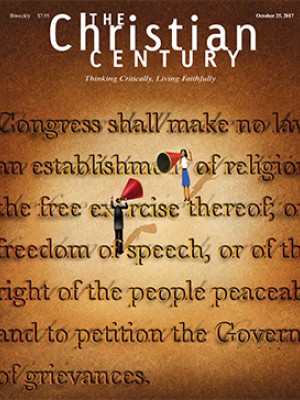

The controversy over athletes kneeling during the national anthem reveals America's unholy trinity of patriotism, militarism, and sports.

“Yankee Doodle” could be our national anthem. Imagine stadium crowds rising to sing it before football games. It’s a song that harkens back to our earliest freedoms won through the Revolutionary War. So why didn’t “Yankee Doodle” ever become our national anthem? It lacks the “emotional resonance . . . [and] gravitas” of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” says historian Marc Ferris. “Yankee Doodle” also happens to lack the military imagery of “the rocket’s red glare” and “the bombs bursting in air.”

In America, we revere a strange alliance of patriotism, militarism, and sports. Most of us take this unholy trinity for granted most of the time. We all but expect that members of the military will be honored at sporting events. We like to be patriotically juiced up before a major clash on the gridiron or in the ballpark. The anthem itself may have nothing to do with sports and didn’t have any connection before a band performed it at a 1918 World Series game, when U.S. casualties from World War I were mounting. But people love to sing it and hear it. And something about our love affair with the mix of patriotism, militarism, and sports has kept it a staple in American stadiums.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Last month President Trump distracted himself from the humanitarian crisis in Puerto Rico by weighing in on the decision of some NFL players to kneel during the national anthem. Ignoring the intent of the action, which was to protest racial inequity in America, especially the pattern of police killing innocent black men and going unpunished, Trump framed the issue as one of respect for the American flag. Deploying what might be a new low of decency in presidential discourse, he referred to any athlete kneeling during the anthem as a “son of a bitch” who should be fired.

It is puzzling that the president would scold athletes who kneel before the American flag while taking so long to condemn white supremacists in Charlottesville who stood in homage to Nazi and Confederate flags. Even more puzzling are the president’s words implying that patriotism belongs to those who associate the American flag primarily with the military. The military doesn’t own the American flag, even if military sacrifice has contributed to its symbolic value.

Schoolteachers, social workers, physicians, humanitarian aid workers, and countless other civilians are also patriots. We all give shape to America’s freedom through various commitments and sacrifices. The flag doesn’t give us meaning and freedom. Together as a nation, we give it meaning through the many ways we uphold the Constitution. Some of those ways even take the form of constitutionally protected protests. The devotion that makes for patriotism ought to be focused less on an inanimate piece of cloth called a flag and more on the hearts and passions of all kinds of men and women who contribute to the value behind that symbolic cloth.

Untangling the interlocking threads of patriotism, militarism, and sports is not easy, especially since power is thickly woven into each. But all who claim a Christian identity get to care about something greater than raw power. We’re beholden to a symbol higher than the flag. We see a cross that strangely wins by losing. It’s that peculiar power that should have us standing and kneeling beside those whom America often leaves behind.

A version of this article appears in the October 25 print edition under the title “What makes a patriot?”