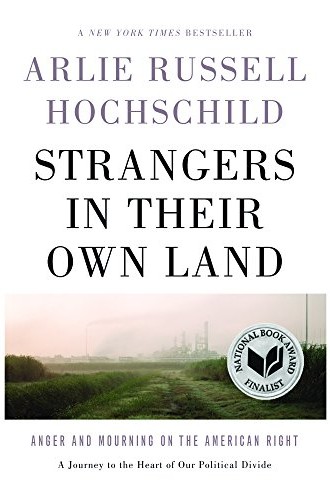

What (some) Trump supporters were thinking—and feeling

A Berkeley academic empathizes with antigovernment Louisianans.

Can a self-described progressive from Berkeley understand and even empathize with Tea Party supporters in the Deep South? Is it possible for any of us to connect across the huge political fault lines in American society? For Arlie Russell Hochschild, an academic sociologist, these are not academic questions. They are as real as the next family reunion. Bringing the extended family together for the holidays can mean confronting America’s political divide over the dinner table.

Our often conflicted efforts to comprehend those on the other side of the divide was exponentially increased by this year’s presidential election. Often I heard people in my blue bubble of Seattle ask, “Do you actually know any Trump supporters?” (as if inquiring about a tribe somewhere deep beyond contact in the Amazon). “I just don’t get it—what can they be thinking?” Reading this book might have helped them.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Hochschild, whose previous work focused mainly on the family and the changing role of women, sets out to understand people on the other side of “our political divide.” And she sets out literally, traveling ten times over five years to Louisiana, where she embeds herself among government-hating Tea Party supporters.

The region of Louisiana that Hochschild studies is an epicenter of big oil and gas—and of devastating environmental impacts caused by those industries. There on the bayous she tries to comprehend “the great paradox.” How can people who have seen their beloved wetlands turned into toxic dumps nevertheless oppose the federal government, the EPA, and regulation designed to stop pollution or get things cleaned up? These people mourn the loss of clean water, the destruction of fish and wildlife, and the death of family members due to epidemic levels of cancer. Yet they support politicians who want the federal government out of their lives. What gives?

Hochschild is resolved to do more than point out the paradox or judge those who embody it. She wants to climb “the empathy wall” in order to see the world through the eyes and experiences of her subjects. This means spending time in people’s homes, on their land and waters, in their churches, and at their family and civic gatherings. Hochschild often has to check her own biases as she works to gain trust and listen deeply. As she does, she finds herself interested not just in the facts but in feelings. How do the people she comes to know in the Louisiana bayous feel about themselves, their culture, and their country?

They feel confused and betrayed, because the rules of how the world is supposed to operate have changed. The narrative through which they’ve made sense of life no longer seems to apply. Worse, that narrative itself is discounted, even disparaged, by much of contemporary American society and its elite.

What is that narrative? The “deep story” Hochschild identifies is about patience, hard work, putting up with pain and difficulty, being optimistic, and being committed to family and faith. It is a story about standing in a long line that, eventually, will lead to realizing the American dream of prosperity and security. The people in line are prepared to wait patiently, doing what they’ve been told they should in order to realize the dream. They hate the way so many people claim to be victims. They don’t believe in whining. Life is tough; suck it up.

But the line is no longer moving forward. It’s stuck, or even moving in the wrong direction. Jobs have disappeared. Wages have stagnated. Most frustrating of all, people are cutting in line. And here’s the clincher: the government is helping them do it. Immigrants, refugees, black people, Hispanics, and some women are getting ahead, while they—who have played by the rules—aren’t. Even some forms of wildlife, like the brown pelican, gets a place up ahead in the line!

When the narrative collapses, explains Hochschild, “you are a stranger in your own land.”

You do not recognize yourself in how others see you. It is a struggle to feel seen and honored. And to feel honored you have to feel—and feel seen as—moving forward. But through no fault of your own, and in ways that are hidden, you are slipping backward.

Larger shifts are at work here. Globalization has meant progress in the fight against poverty worldwide, but with a downside for at least some American workers. The move from an economy based on extraction of natural resources (logging, mining, fishing) to a service economy means fewer jobs for those who do hard physical work and more jobs for “knowledge workers.” Amid these seismic shifts, there are others: America is moving steadily toward being a society where people of color are the majority. And Protestant Christians, once the dominant majority, are already a minority.

As Hochschild was concluding her work in Louisiana, Donald Trump emerged on the scene like a flame to dry kindling. She explains:

Since 1980, virtually all those I talked with felt on shaky economic ground, a fact that made them brace at the very idea of “redistribution.” They also felt culturally marginalized; their views about abortion, gay marriage, gender roles, race, guns, and the Confederate flag all were held up to ridicule in the national media as backward. And they felt part of a demographic decline.

One of her subjects summed it up this way: “there are fewer and fewer white Christians like us.”

It’s easy to dismiss those who hold such views as racist, backward, and benighted—which is exactly how Hochschild’s subjects feel they are viewed by the larger culture and its elites. This sense of marginalization makes them vulnerable to the seductions of political figures who declare that the government is the enemy, that free-market capitalism is their best hope, and that it’s time to “make America great again.”

Denigrating such people, as Hillary Clinton did in her infamous “basket of deplorables” remarks, while politically easy and psychically gratifying, is asking for trouble. Moreover, it’s blaming the victim. For even if Hochschild’s subjects hate the idea of being thought of as victims, they are. They are victims of social and demographic changes, and more insidiously, victims of the manipulations of very wealthy conservatives like the Koch brothers. The Kochs and those like them have been masterful at exploiting the fears and frustrations of the kinds of people Hochschild befriended.

These days, progressives are often urged to make friends across racial and ethnic lines as a part of the work of understanding white privilege and dismantling systemic racism. Perhaps friendships need to be pursued on other fronts as well. How about an effort to make friends among those on the other side of the political divide, among those who you may be tempted to dismiss or to write off as backward and deplorable? Jesus, after all, did not come to save the righteous but sinners—another word, one might say, for deplorables. Moreover, it is a category that includes us all.

A version of this article appears in the December 21 print edition under the title “Listening to Louisiana.”