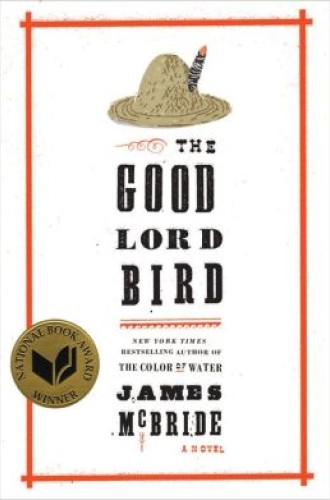

The Good Lord Bird: A Novel by James McBride

I didn’t want to review this book. I just wanted to enjoy it. At every turn, it resisted my attempts to analyze it and replaced my literary critic’s instincts with laughter, pleasure, and suspense.

The Good Lord Bird, last year’s National Book Award winner, is a tale of the antebellum South perhaps like none you’ve ever heard. A young slave living in the contested territory of Kansas, Henry Shackleford, is liberated by John Brown, who will later try to ignite a slave revolution by attacking Harper’s Ferry in what is then Virginia. Because the 11-year-old boy is small, has a beautiful face, and is wearing a potato sack, Brown believes him to be a girl and takes the boy’s father’s dying words, “Henry ain’t a . . .” to be “Henrietta.” (This “is how the Old Man’s mind worked. Whatever he believed, he believed. It didn’t matter to him whether it was really true or not. He just changed the truth till it fit him. He was a real white man.”) For the next three years, Henry is known as Henrietta or, in Brown’s affectionate terms, Little Onion, whom Brown believes to be his good luck charm. Onion travels with Brown as he fights the Pro Slavers in Kansas, raises money and support back east, and prepares his doomed raid on Harper’s Ferry.

The story is told in Little Onion’s irreverent yet innocent voice. From the beginning Onion says that he doesn’t want to be in Brown’s ragtag army and that at any moment he will break free and run away. But the charade goes on so long that Henry becomes some piece of Henrietta, and the affection that Onion has for John Brown also grows more real.