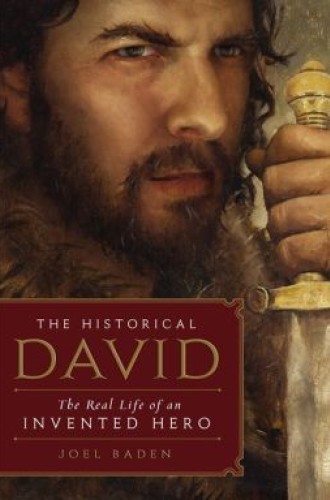

The Historical David, by Joel Baden

The public has a taste for biographies of great people who on closer inspection turn out to be not so great after all. The curtain has been pulled back on Thomas Jefferson, Bill Clinton, Mother Teresa and even Jesus.

We should be weary of the revelations: home-run hitters admit to using performance-enhancing drugs, politicians turn out to have swindled us, trusted clergy and coaches are found to have misbehaved. Our craving to hear more debunking tells us a lot about our low estimate of human nature and about the feeble expectations we have of ourselves. But it also reveals a moral core. We are appalled by the revelations because we know not to cheat; we shake our heads because we know how to be good and we want to be good.

Best sellers have been mocking Jesus for some time now. We may suspect that Jesus is accustomed to this, having learned the hard way when he was on Earth. Now other biblical characters are being subjected to reductionist critiques as well. Joel S. Baden, an associate professor of Old Testament at Yale Divinity School and author of The Historical David, assumes that religious folk are unaware of David’s real life and think of him as a hero—the sweet singer who composed Psalms and was prayerfully submissive to God and bold in fulfilling God’s plans.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Admittedly, the Bible occasionally whitewashes David and exaggerates his piety—for instance, in the paean of 1 Kings 14:8, which claims that David followed the Lord “with all his heart, doing only what was right.” But anyone who has paid even cursory attention to the narrative in 1 and 2 Samuel will realize that David was rather bawdy and did not shrink from chicanery and violence or from adulterous coercion. There may be spiritually oriented people who would be shocked to learn that David was more than the slayer of Goliath and that he did not compose the Psalms, but I doubt there are many. Church members I polled either already know a lot about David, including his dark side, or aren’t involved enough with Bible narratives to care.

Baden wishes to eviscerate “the idea of David—an abstracted, romanticized, idealized figure.” But for me and most students of the scriptures I know, it’s the ambiguity, the complex mix of lunacy and faith that makes the unidealized David so appealing. Based on the opening section, I thought this was where Baden would lead us.

But his dismantling of David, his zeal to prove that David wasn’t a nice guy at all, grows more savage as the book proceeds. When demonstrating that David didn’t write the Psalms, Baden is fair, even-handed and clear, as he is when explaining the geography and nature of the early Israelite state (and how small and fledgling it really was). But then he argues that David didn’t marry Michal, that David killed Saul and certainly didn’t grieve Saul’s death, that David killed Absalom and didn’t grieve his death either, that Nathan is a made-up character, that the Bathsheba affair didn’t happen but was invented to conceal the explosive truth that Uriah was Solomon’s “real” father, that Ahitophel didn’t commit suicide but was killed by David, that David’s merciful treatment of Mephibosheth cannot have happened, and so on.

Baden’s summation of the real David? “He was not kind or generous, he was not loving, he was not faithful, he was not honorable, he was not decent. He was ambitious, . . . a vile human being.” This conclusion drives the spin Baden takes on every story.

While we cannot prove that Baden is wrong, his methodology is suspect at every turn—hardly what one would expect from an Ivy League scholar. For Baden, anything that serves a literary purpose didn’t happen, such as the marriage to Michal. Saul is a literary foil for David—but does that falsify his part of the story? Isn’t history littered with situations in which a leader serves as a foil for the successor? We wouldn’t say that Neville Chamberlain didn’t really appease Hitler because this served as a foil for Winston Churchill, or that Nelson Mandela didn’t really fight apartheid because F. W. de Klerk was a foil for him, would we?

Absalom didn’t hang by his hair in a tree, Baden claims, because the story is clearly presented as a morality lesson. We can’t prove that he did or didn’t, but don’t actual events take place all the time that may then stand as morality lessons? Isn’t reality the crucible in which morality lessons are concocted?

Baden labels certain moments in the narrative as “private” or “unverifiable” and concludes that they did not occur. Thus David wasn’t anointed, Saul didn’t visit a witch, David didn’t see Bathsheba bathing, and David didn’t spare Saul’s life in the cave. But then Baden substitutes a counternarrative replete with events that not only are private and unverifiable, but have as their only basis guesswork on Baden’s part; every page features “so it must have been” or “we may safely assume” arguments to fill in between the lines.

It is a trait of all the Bible debunkers, from great scholars like Bart Ehrman to fictional luminaries like Sir Leigh Teabing, to accept this or that Bible detail as fact while dubbing another detail a lie. But how do they pick and choose? Isn’t it odd that Baden lifts up Shimei’s insulting speech against David as “the historical truth the biblical authors have tried to counter”? In the margin I scribbled, “But it’s in the Bible!” Did the biblical authors’ pens betray themselves?

Baden’s hermeneutic begins with taking whatever people think about David and proving it to be wrong, then shifts to arguing that the truth about David is the most negative possible spin on what the Bible actually tells us. We are left with a monolithic, narrowly malevolent, predictable and thus frightfully boring character no one would have followed or loved, a figure that history would not bother to remember. All people are complex, an unfathomable mix of the lovely and the dastardly. Why is depth of personality implausible to Baden? Some of the most ruthless rulers in history have been megalomaniacal killers and yet tender with their families and lovers.

Isn’t history, and life as we know it, strewn with ambiguity? You do fight against someone you love, but you do not wish them dead, and when they die you surely grieve—perhaps more intensely—even if you’ve had a fractured relationship. A wooden David who would kill Saul at the earliest opportunity, who would kill his own rebellious son and then not grieve, is far less compelling or even conceivable than the kind of person the Bible, with startling candor, portrays as devious and yet rising at times to nobility, as one who desperately wanted to be king but could wait for the right moment, who would fight an unsought civil war against his own son and then grieve not only the son’s death but the whole sorry mess, who loved women for crass purposes but then could do some real loving in the thick of it all.

History, not just the Bible, invites us to contemplate such paradoxical, fascinating people—for they are like all of us, which makes for far better reading (and thus living) than the kind of colorless, icy person I’ve never encountered, but who Baden insists was David.

Baden’s agenda might manifest itself in his conclusion, where he suggests that we “should be proud of the fact that we find the historical David repelling”; that “the more we see David is not like us, the more we see how far we have come”; that “we are not constrained by the past.” The arrogance of this progressive viewpoint makes me shudder. I tremble not so much over the “real David” we may have left behind, but over the real today that we notice in the news and in the mirror, and realize we’ve not come so very far at all.