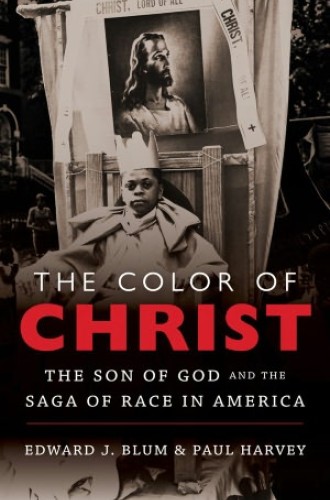

Jesus in black and white

The Color of Christ confronts the complicated history of the Christ image and racial politics in the United States. The authors’ ambitious—some might say audacious—aim is to track “the creating and exercise of racial and religious power through the images of Jesus and how that power has been experienced by everyday people.” Their professed task is tantamount to telling the story of American Christianity in its manifold manifestations and interpretations across four centuries. In this bold project, Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey have produced a rich and readable narrative that begins with the Puritans and concludes with Jesus in the age of Obama.

Blum and Harvey are two of the more productive chroniclers of American religion on the scene today. The duo has collaborated as coeditors of The Columbia Guide to Religion in American History (2012), as well as on the Religion in American History blog, where Harvey is editor. As historians who specialize in the southern region of the United States at the dawn of the 20th century, they have helped to advance the field of U.S. religious history in both print and digital media.

Readers familiar with Stephen Prothero’s book American Jesus will recognize the narrative arc of The Color of Christ, but the two volumes should not be confused. Blum and Harvey’s diachronic account of the changing face of the Christ figure demonstrates an impressive collection of data, which includes artwork, sermons, music and personal testimonies. They present a dizzying number of illustrations from about seven historical epochs. In the process, we learn how people of faith—most notably white and black Protestants, white Mormons, Native Americans and European Catholic immigrants—rejected, embraced and interpreted the sacred Christ image across religious, racial and class lines.