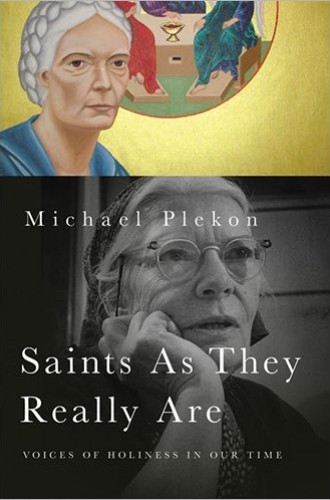

Saints As They Really Are, by Michael Plekon

Michael Plekon is a man of many talents: he is a sociologist, an anthropologist and an expert in Kierkegaard’s thought. His spiritual pilgrimage includes converting from Catholicism to Lutheranism to Eastern Orthodoxy. His writing reflects all of this variegated experience, and for that reason it is sometimes tough to follow.

This new book on saints is not really about saints at all. After retreading some of the themes explored more popularly by Jesuit writer James Martin in My Life with the Saints and then by theologian Elizabeth A. Johnson in her highly regarded feminist critiques of traditional Catholic understandings of saints, Plekon turns to sociologist Peter Berger, his former professor at Boston University, for a framework for Saints As They Really Are. Plekon tells us that Berger “rightly insists that kenosis, the self-emptying suffering of God and victory of resurrection, is the center of faith.” This seems a bit like quoting Julia Child on the architecture of Languedoc, but never mind. Plekon sets off to explore holiness. That’s what this book is about.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Plekon articulates a definition of holiness derived from the thought of the Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev: “The opposite of evil is not virtue but goodness, Godliness, holiness.” He follows this with: “Holiness is a gift, and it is given to every child of God.” Six pages later, he explains that as a gift from God, holiness is given “according to the overflowing love and the wisdom of God”—and that this happens across religious boundaries, in “the Old Covenant and Islam, even Hinduism, Buddhism, and humanism.” This vision of sainthood is expansive to say the least, and it stands in stark contrast to the official perspectives of the Catholic, Lutheran and Orthodox churches.

As a study in human movement toward God, Plekon’s book goes beyond the saints per se, even though it remains a study of saints qua saints. Instead of looking at the lives and writings of the famous holy departed, he explores the writings of dozens of contemporary memoirists and their quests to be holy. His list of subjects is interesting: it includes Sara Miles, Lauren Winner, Barbara Brown Taylor, Nora Gallagher and Diana Butler Bass. At times I wondered if his book had started as an essay specifically on prominent Episcopal women.

But the most interesting pages—and the reason I would recommend this study to anyone interested in how personal narratives reflect the divine at work—are those in which Plekon shares stories of his own religious disappointment and spiritual aspiration during his years in Carmelite formation as a younger man. This is the bulk of the book’s middle. Plekon tells his story with honesty and careful attention—and without regard for self-image. He’s learned much from the best-selling memoirists to whom he devotes so much space elsewhere in the book. He offers up religious ugliness as well as the good and the beautiful and hopes to learn from it all. He acknowledges again and again the essential dichotomy of our existence as spiritual people: being human, we are fallible, proud and selfish, and yet God is teaching us to be like God. That’s sainthood. Or holiness.

I am particularly struck by the ways in which Plekon’s story seems to echo with what he admires in others’ narratives. For example, he writes:

I am powerfully drawn to Patricia Hampl’s remembering—to her youthful rejection of her Catholic upbringing and her complicated rediscovery of the contemplative life, of the psalms and the liturgy, of the scriptures and the holy women and men who form a long procession from the first days of Christianity down to the present.

All of our lives are full of these sorts of divine rejections and discoveries, but we don’t all recognize them as clearly as Plekon does.