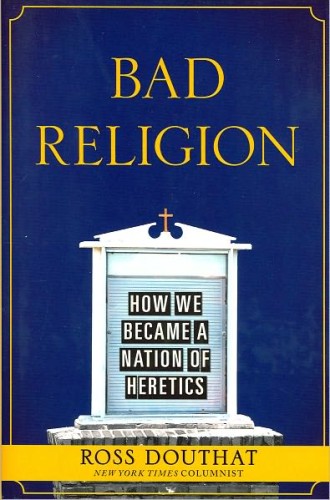

Religion in decline?

Ross Douthat knows how to throw a punch. Readers accustomed to his regular New York Times op-ed column likely will expect Bad Religion to be a moderately conservative, carefully nuanced book. It is not. Bad Religion offers a deeply conservative, hard-hitting examination of the devolution of American Christian culture from the high ground of the 1950s into the swamp of the 2000s. It calls modern Christians to return to the intellectual rigors and ethical demands of their historical tradition. Douthat does not frame his call in the roundly qualified locutions of the academy but in the straightforward, almost adversarial prose of a prosecutor’s brief. Here’s my case, he effectively says. Consider it, make a decision and think and live accordingly.

The book’s argument is clear and simple. In the boom of economic and cultural confidence that followed World War II, the main or central or orthodox (he uses those terms interchangeably) stream of Christianity exercised commanding influence in the broader reaches of American life. Douthat supports this claim with an array of statistical data about church building and attendance, but the argument mainly rides on the rails of four case studies: the midcentury careers of the Reformed intellectual Reinhold Niebuhr, the evangelical preacher Billy Graham, the Catholic television personality Fulton J. Sheen and the Baptist social reformer Martin Luther King Jr. Though these men represented different traditions and outlooks, individually and together they exerted both extraordinary and extraordinarily constructive influence on the culture.

Enter the 1960s and things began to fall apart. Multiple influences flowed together, including the growth of political partisanship within the churches, the destabilizing (albeit liberating) effects of contraception, the relativizing impact of the new global consciousness, and the unprecedented surge of financial prosperity, which left traditional vocations less attractive and the three-day weekend more attractive. Seeking to accommodate rather than challenge those trends, uncounted Christians followed Harvey Cox and friends into the Secular City.