Devout atheist

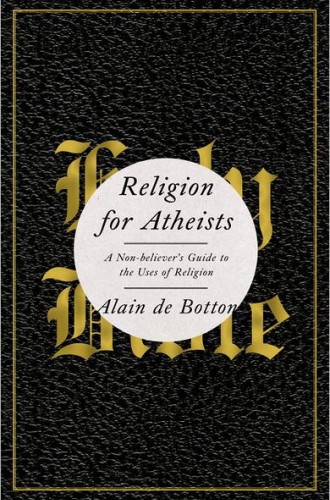

Modernity can be defined as the effort to retain the benefits of religion—moral purpose, social cohesion and aesthetic power—without the hazards of religious belief. Participants in this project may exhibit sunny enthusiasm, confident that life without God is uncomplicatedly liberating, or wistful regret, aware of the many riches that are left behind. Or, as in the case of essayist Alain de Botton, they may be deeply ambivalent.

De Botton is officially enthusiastic, but his book is wistful. He insists that unbelief has been liberating for him, but he describes with undisguised envy the wisdom of religious practices. He asserts that there is no reason atheists cannot draw on the “most useful and attractive parts” of religion to enrich their lives, yet he offers only a few whimsical examples of how to do this. His nonbeliever’s guide is so sympathetic to religion that it reads at times like a work of apologetics. Atheists who pick it up may find themselves undergoing a crisis of faithlessness.

De Botton begins with an appreciative, atheistic account of the Catholic mass, which he presents as a robust alternative to the sterile individualism of modern life. (Catholic Christianity is his primary reference point, though he occasionally alludes to forms of Protestantism, Judaism and Buddhism.) He sees how the beauty of the worship space, the words of the liturgy and the interactions of the worshipers inspire a sense of common humanity. He admires how the mass gathers people of different ages, races, professions and social status around a moral vision. He notes that the mass inculcates compassion by acknowledging sins and honoring a suffering man who was “nothing like the usual heroes of antiquity.” The church shrewdly centers all this activity in a shared meal, evoking profound feelings of community.