Muckraking pilgrim

It is late 2009 and Sean Hannity of Fox News is interviewing Michael Moore about his film Capitalism—A Love Story, in which the unmitigated and largely unregulated corporate greed that led to the Great Recession is described as “sinful.” Moore is decked out, uncharacteristically, in a suit coat, white shirt and dark tie. Maybe he’s trying to look like a capitalist. Or a Republican.

In his amiable opening banter, Hannity allows as how Moore is an “unapologetic socialist—are you not?”

“Christian,” the filmmaker corrects him. An unapologetic Christian. “I believe in what Jesus said.”

“I’m a Christian,” replies Hannity, as if his being one means Moore can’t be. “I did theology.” But Moore is comfortable with faith-based conversations. “Are you Catholic?” he asks Hannity. “Did you go to mass this Sunday?”

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

In both of their memories of boyhood, a nun tells them that missing mass on Sunday is a mortal sin. For all their differences, they both recognize their common roots in the boggy, priest-ridden island nation that sent millions of its starving sons and daughters to these shores. They both inherited gifts of gab and grievance, the knack for using language as balm and bludgeon—and easy access to shame and guilt.

Moore asks the host what the gospel and sermon were about. Hannity claims he can’t remember and moves, a little nervously, to change the topic.

“It was only two days ago,” says Michael, pleased that he may have caught Hannity in a fib.

Later in the same year, Wolf Blitzer on CNN suggests that Moore is a “left-wing Democrat” and a “multimillionaire” and asks him outright if he’s a socialist.

“I’m a Christian,” Moore tells him. He believes, he explains to Wolf, that we’ll all be judged by how we treat the least among us.

This exchange is replicated whenever Moore is interviewed. He says it to Charlie Rose and Bill O’Reilly, to the women on The View and anyone else who wants to know. He makes plain that while he’s “done very well” as a documentary filmmaker and best-selling author, though he has homes in Manhattan and in Michigan, he acts out of a moral code learned from the Baltimore Catechism and from nuns and priests and from his parents growing up in Davison, Michigan, southeast of Flint. His working-class roots and religious pedigree are beyond refutation. No one is asking to see his baptismal certificate.

It would be easy enough to write off Moore as a passionate but otherwise cartoonish figure in our national media mud-wrestling match—a counterweight and perfect foil for Rush Limbaugh or Ann Coulter—another bombastic, blathering player in the bread and circuses culture of YouTube and cable news, Twitter feeds and infotainment. God knows he is loathed by a predictable segment of the population, most of whom have never seen his films or read his books.

But considered in light of his religious formation and practice, Moore’s books, films and public homiletics can be seen as the work of a pilgrim, a saved and repentant sinner, called to bring the news—not all of it good—to folks who would often rather do without it. His version of the truth challenges theirs, and he is happy to have the debate because, more often than not, history has proven he was on to something.

Much as some would like to dismiss him, Moore won’t go away. His output in the past ten years alone has been prodigious: best-selling books, blockbuster movies and an endless circuit of lectures at universities and theaters around the country. He’s been an Eagle Scout and altar boy, activist and seminarian, gadfly and agitator, muckraker, movie star, college dropout and popular writer—as well as the most successful documentary filmmaker in history. And in each of these enterprises and endeavors he has been, unambiguously, a Christian. Which is to say he is guided by religious claims and a profession of faith that proceed from an Irish Catholic family history, a nunnish education, the constant devotions of religious practice and a more than passing familiarity with the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth.

In a country plagued by political difference and bedeviled by religious divides, Michael Moore poses some vexing questions into the maw of certainty and self-righteousness: Whose side is God on? What would Jesus do? Are we not our brothers’ keepers? And he seems determined if not to take Christianity back from the evangelical right, at least to require that it be shared and shared alike.

When President Obama spoke at the National Prayer Breakfast earlier this year, he cited the Gospel of Luke as a basis for his proposal to increase taxes on the wealthy. “For me, as a Christian,” he said, the proposal “coincides with Jesus’ teaching that ‘for unto whom much is given, much shall be required.’ It mirrors the Islamic belief that those who’ve been blessed have an obligation to use those blessings to help others, or the Jewish doctrine of moderation and consideration for others.”

Ralph Reed, late of the Christian Coalition and now with the Faith and Freedom Coalition, responded that for the president to tie his tax policy to Jesus’ teachings “is theologically threadbare and straining credulity.”

“I felt like it was over the line and not the best use of the forum,” Reed said. “It showed insufficient level of respect for what the office of the president has historically brought to that moment.” For no few among the evangelical right, Obama as legitimate Christian is an unacceptable notion. That Obama can use Christian language is simply the basis for more distrust.

If Barack Obama is seen by the right as a Robin Hood out to redistribute wealth, Michael Moore may be the happily subversive Friar Tuck. In his dark-hooded sweatshirt he looks a little like Tuck, a monk in his cowl, fashionless as any Franciscan, baggy in his habits.

It is going toward midnight on a midwinter Tuesday, and we are sharing Chinese takeout at his home in New York where the talk has turned to the “existentials.”

“I was supposed to be building Buicks,” he tells me. “I got to do this instead. I think I’ve made a contribution.” The gratitude in his voice is genuine and palpable. His voice is devoid of polemic or urgency, replaced by calm and meditative tone.

He recounts his decision a few years ago to get rid of the security team of former Navy Seals that had been hired to protect him against threats to life and limb that were made following his Oscar acceptance speech at the Academy Awards in March 2003.

“A voice in my head kept telling me to just go up, take the prize, thank my agent, and go on home. But I couldn’t.”

Moore made his remarks—spoke truth to power, such as he knew it—without the advantage of history and hindsight. He spoke out four days after the U.S. bombing of Iraq had begun to an audience of his colleagues and a worldwide TV viewership, most of whom approved of the “shock and awe” and advancing ground forces. They would rather the gala evening not be spoiled by dissenting voices schooled in just war theory and UN resolutions. Moore left little doubt about his outrage.

“We live in a time when we have a man sending us to war for fictitious reasons. Shame on you, Mr. Bush, shame on you. And any time you’ve got the pope and the Dixie Chicks against you, your time is up. Thank you very much.”

His time was up. The red-lit prompter was flashing. The mic was lowered into the floor and he was hurried off the stage, clutching his trophy, while the band began to play over the shouts and booing of the assembled.

“Asshole,” a stagehand shouted into his ear. There was some pushing and shoving and they got him out of there.

He was booed off the stage in Hollywood and shunned at the afterglow parties. In Michigan someone dumped truckloads of horse manure in his driveway. People nailed signs to their trees: Get Out! Move to Cuba! Commie Scum! Leave Now or Else! There were phone calls and hate mail, random sidewalk attacks and hundreds of credible threats. A man in Ohio with an arsenal and a hit list and plans to blow up Moore’s residence in northern Michigan was arrested and sent to jail. Thus the bodyguards and security fences, thus the low-grade ever-present fear of harm to himself or someone he loved. Eventually he learned to live with the fear, not by going into hiding but by going to work. He wrote books, made movies, traveled the English-speaking world advancing his causes.

“I’d come to the conclusion that I had lived a good life; I had raised a good kid; I’d been a good and faithful husband. There’s nothing on my conscience I feel bad about. So if it is going to end tonight, it’s going to end tonight. I’d rather just accept that than live in fear. And as soon as I truly felt that, it was liberating. I was no longer afraid. I’d come to that peace.” He sounds like someone who’s been born again.

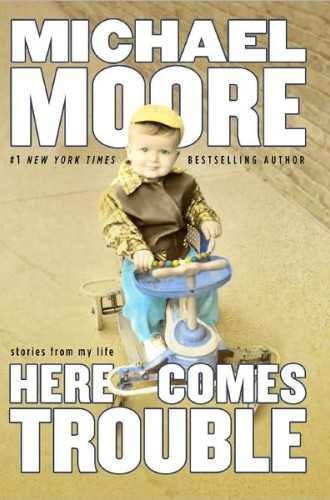

Like many of his films, his autobiographical book Here Comes Trouble asks us to consider not the sweeping issues of good and evil but the more mundane issues of right and wrong.

“By the age of eleven, I was fascinated with history and politics. For this, along with those too-early reading lessons, I blamed my mother.” The book is dedicated to his mother, “who taught me to read and write when I was four.”

Veronica (Wall) Moore seems very much the moving force behind her son’s bookish habits and personal odyssey. And the chapter that details her life and times and death in 2002, “Pieta,” seems the heart and soul of Here Comes Trouble. It is his studious and deeply religious mother who shapes the larger worldview that informs his work in words and film and public discourse.

“My mother’s love of country, its government, and its political institutions was always evident. She saw it as part of her parental responsibility to school us in the values of a democratic republic, specifically this one: the United States of America.”

In the summer of 1965, she loaded her only son and his sisters into the family Buick and drove them to the nation’s capital for a look at the White House, the Washington Monument, the monument to Iwo Jima (his father, Frank, was a combat marine in World War II) and the first Catholic president’s eternal flame at Arlington. When he finds himself lost in the Capitol Rotunda, it is the kindly junior senator from New York, Robert Kennedy, who helps him find his mother again. They sit in the Senate gallery to hear the debates on Medicare and a few days later hear the House debate the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

After seeing all they could in Washington, D.C., Mrs. Moore drove her children north to see the World’s Fair in New York. She’d been with her father to the 1939 World’s Fair and knew what it meant to get a glimpse of the future. But a glimpse from the past turns out to be the watershed moment of that remarkable summer tour.

At the fair, “the longest lines were reserved for the Vatican City pavilion,” recounts Moore. “For it was inside this edifice that the pope had sent abroad, for the first time ever, . . . one of the most famous works of sculpture in the history of the world: the Pieta, by Michelangelo.

“Here was Mary holding her only son—her dead son—but she wasn’t sad! Her face was young and smooth and . . . content. What could be a worse moment in anyone’s life, to lose one’s child? And to have it happen in such a violent, barbaric way. . . . And yet, there was no sign of any violence in the Pieta, just a mother gazing down at her son as he slept in her arms. And that was what Jesus looked like—serenely asleep in her arms. No blood from the crown of thorns, no hole in his side from the Roman’s spear. It was as if he would wake up at any moment—and she knew it. There was death but there was life.

“I couldn’t take it much further than that—I mean, I was eleven!—but it was profound and it had my head spinning . . .”

The black-and-white photograph from the family album that serves as a coda to “Pieta” is a snapshot of the young mother, Veronica Moore, holding her infant boy Michael in her arms. Seated on a sofa in the family bungalow on Hill Street in Davison, she is wearing white anklets and a print dress and is the image of motherhood circa 1954, smiling at her firstborn baby, who is smiling back. For Moore, the sculpture was a study in love and grief. When the mother died after a brief illness in 2002, it is the son who holds the mother in his arms.

I was the last in the room. I went over to my mother and held her. I kissed her on her head, and when I pulled back I noticed a long gray hair of hers on my shirt. To this day, that last strand of gray hair still sits in that same shirt pocket, folded up in a small bag in my old bedroom in the home I grew up in, hidden away, untouched, up on top of the bookshelf, next to a little plastic statue she gave me at the New York World’s Fair of Michelangelo’s Pieta.

One gathers that the joyful and sorrowful mysteries of life and death, love and grief, family life and the life of faith that inform Michelangelo’s artistry inform Moore’s work as well. His work is freighted with religious references and moral codes learned from the lessons his mother taught him.

It is simply easier to think of him as a socialist attacking capitalism than as a practicing Catholic Christian invoking the gospel in defense of democracy.

He is, after all, an easy target. He’s tall and amply padded and moves at a slug’s pace. When he takes the stage at the Michigan Theater in Ann Arbor for the final curtain of a three-month book tour, he is almost nunnish in his disregard of fashion, in sweatpants and T-shirt, sweatshirt and baseball cap, tube socks and tennis shoes, his plump grinning mug like an incarnation of Sr. Innocence who taught you to diagram sentences in elementary school. He seems like a cross between John the Baptist and Mark Twain, all theater and word works, rant and incantation, a radical believer who knows how to act out the mysteries of faith.

“The only reason I left the seminary is because I like girls,” he tells me toward the end of our conversation. “Once puberty or whatever it is kicked in.” He laughs. All the same, he still feels a calling to bring the news to those who will hear it. “At some level I never left the seminary.”

When I first met Moore in the summer of 2000, he was stumping for Ralph Nader because both national parties, as far as he was concerned, had sold out to the larger corporations that moved American jobs out of America. Bill Clinton had signed NAFTA into law, Flint was blighted by unemployment, and the national manufacturing base was in the process of collapsing. Nader’s candidacy, especially in swing states like Florida, was sufficient to deny Al Gore a clear victory and thereby helped put George W. Bush in the White House.

In the years of Bush’s presidency, Moore worked at a feverish pace. He brought out four hugely popular documentary films, wrote three best-selling books and spoke at hundreds of universities here and in Europe. “The Bush years were more than prolific for you,” I tell him.

“I went on a tear,” he replies. “I couldn’t forgive myself. Especially in the first months of the war, when you’d hear reports of the dead soldiers and the dead Iraqis. I felt responsible on some level. I’ve never really let myself off the hook.”

One of the chapters in Here Comes Trouble records Moore’s friendship with Father George Zebelka, an army–air corps chaplain during World War II who blessed the bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The chapter details the priest’s lifelong anguished pursuit of forgiveness. “I’m praying for justice tempered by mercy when I meet my Maker,” said the priest, who died ten years ago. Moore has taken the priest’s painful case and good counsel to heart.

For George Bush’s misadventures in Iraq—a war of choice waged on a pretense with the apparent approval of a lazy press, a too trusting Congress and a disengaged populace—Moore is doing penance, seeking justice and mercy for his part in it. A people willing to trade just war principles for “shock and awe” and reelect a president who declares “mission accomplished” while real soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines remain in harm’s way; a people who sit too quietly by while that commander in chief authorizes torture, disallows coverage of our war dead’s return; a nation that allows a fraction of a fraction of the population to actually go and fight wars while the rest go off to the mall or megachurch or golf course—all this is a sign of a nation that hankers for the ridiculous over the sublime, diversion over engagement, bread and circuses over difficult truths. If Congress declares war and a president commands armies to fight, it is nonetheless the nation that wages war—we the people, every one of us in whose name such things are done.

For more than a quarter century Moore has called us to examine our national conscience. From the blighting of his hometown in Michigan by General Motors, to the perfect storm of gun culture, violence and disenchanted youth that became the Columbine tragedy, to the new century’s original sin of using 9/11 as a predicate for the Iraq War, to the unabashed greed of the financial industry that gave us the Great Recession, he has trained his eye and the lens of his camera on the nation’s mortal and venial sins and asked if there aren’t ways we could better be our brothers’ keepers.

“If I have a clarion call, it is: Everyone off the bench. Everyone in the game. Citizenship is not a spectator sport.”