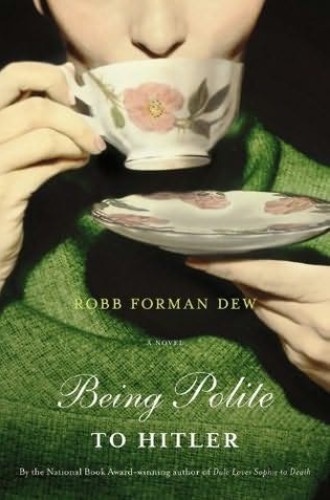

Being Polite to Hitler, by Robb Forman Drew

To the fictional Julian Brightman, an obtuse maker of propaganda films for the U.S. government, Washburn, Ohio, is the town "most representative of ordinary life in the United States during what he characterized as the prosperous and serene aftermath of World War II." Here he sets his camera to work to enlighten the world about the lives of ordinary Americans. But in this final novel of Robb Forman Dew's trilogy about the fortunes of the extended Scofield family during the course of the 20th century, Washburn's citizens are anything but serene. What impact, Dew asks, do the large social, political and natural events of our time have on our mundane lives—and what influence can we have on the larger world?

Being Polite to Hitler begins in 1953 on the day when, to the dismay of Agnes Scofield, the novel's central character, the Yankees again win the World Series; when an extended heat wave and drought parch the country's heartland; and when, in Washburn, a young child screams in terror because she mistakes a factory's noonday whistle for an air-raid siren announcing a nuclear attack. That evening, at a dinner party for Robert Butler, the founder of an influential literary review (Dew is the granddaughter of poet John Crowe Ransom, who founded the Kenyon Review at Kenyon College in central Ohio), people argue about the necessity and ethics of dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Earlier in the day, Robert's wife, Lily, a seemingly ordinary, cheerful woman in her sixties, roasts a turkey and a ham for the party and muses that "if she allowed herself always to consider everything she knew . . . well, she doubted if she would even bother to get out of bed in the morning." On that day she is especially annoyed by the illustration of the Doomsday Clock that decorates her morning paper. She realizes that "some sort of call to action was implied" but bristles "at being manipulated into feeling responsible for the apparently inevitable use of the atomic bomb."