Twain’s sorrows

By the time Mark Twain died in 1910 his celebrity exceeded that of presidents and kings. His works had been published on both sides of the Atlantic and widely translated. They were also pirated by Canadian publishers—an act of literary theft that moved Twain to appear personally before a congressional committee to lobby for more stringent laws to protect intellectual property. He had made and lost a fortune and enjoyed long friendships with some of the nation's most influential intellectuals and businesspeople. Among those were both William Dean Howells, "dean of American letters," and Henry Rogers, infamous head of Standard Oil. A simple list of the friends he delighted and enjoyed over the decades of his variegated career would provide ample testimony to the capacious reach of his tastes, ambitions and tolerance.

Twain's large appetites were matched by the restless energy that took him across the country several times and back and forth to Europe many more times, to places where he divided his time between lecture halls and billiard parlors. One of his proudest achievements was the honorary doctorate of letters he received in 1907 from Oxford University, a consummation he greeted with the comment, "For 20 years I have been diligently trying to improve my own literature, and now, by virtue of the University of Oxford, I mean to doctor everybody else's." But his deepest joy came from a long, happy marriage to his beloved (and long-suffering) Livy, whose death six years before his own, along with the deaths of two of his three daughters, left him bereft.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Numerous biographers have relied heavily for their understanding of Twain's final years on his autobiography and the authorized 1912 three-volume biography by his friend Albert Bigelow Paine, both of which offer evidence of growing bitterness, cynicism and disillusionment with church, state and social hypocrisies. But a rereading of the compendious record of those years, including over 5,000 letters that have been available at the University of California-Berkeley since 1966, modify this picture. In fact, as Michael Shelden shows, Twain's characteristic humor, his tenderness toward others' children and grandchildren, his lively interest in public affairs and scientific discovery, and his wide hospitality survived the harsh disappointments and losses that afflicted him in his final years.

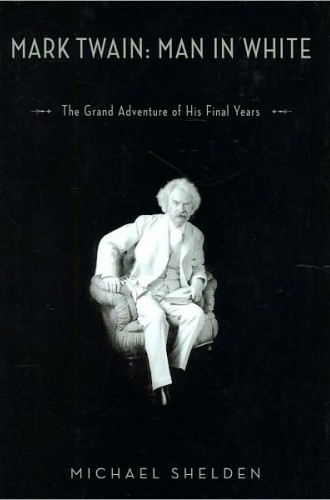

Shelden's Mark Twain: Man in White offers not only the satisfaction of a generous reconsideration of Twain's complicated personality and unsettling genius, but also the pleasure of well-told anecdotes liberally punctuated by Twain's own inimitable words on life, writing, faith, friendship, falsehood and, with increasing urgency, social justice and public policy. Shelden insists on the need to correct the popular image of an embittered misanthrope that has been attached to the aging author. "In our modern eagerness to highlight his darker side," he writes, "we do him a disservice by pretending that his matchless sense of humor suddenly failed him in his last years." And indeed, the liberal excerpts from his letters and late works suggest a mind still lively and clear and an unabating, albeit more acerbic, wit.

The volume's title introduces what Sheldon sees as a defining image of Twain in later life: the white suit—shockingly out of season and slightly exhibitionistic—that he wore so frequently on public occasions that it became a trademark. Indeed, on at least one occasion an audience vociferously complained when he appeared in more conventional gray. He eventually had his London tailor make six identical white suits to provide for more frequent use.

The opening story in this copiously researched collection is an account of his appearance before the congressional committee on patents to argue for revised copyright law—the occasion on which he unveiled the white suit. The gesture was strategic: the attention he attracted and the good humor he elicited softened the tone of the debate and seems to have contributed significantly to approval of several provisions he supported.

Twain had no particular compunction about using his celebrity to advantage. "He wasn't ashamed to seek attention," Shelden writes. As Twain himself explained, "The desire for fame is only the desire to be continuously conspicuous and attract attention and be talked about." He succeeded on all counts.

That success required ongoing attention to the public that had made him a superstar and to the image he chose and crafted as deliberately as he chose what became one of the most famous pseudonyms in history. Shelden suggests that he even strategized about maintaining his public presence for decades after his own death by "piling up manuscripts to be published only after he was gone." Twain explained that "he wanted to entertain posterity by leaving to his heirs the job of issuing new works every decade or so. These were meant to go off like time bombs, each intended to cause a periodic ruckus, keeping his name in the news and his fame alive."

The fame came at a high cost. Twain wearied of lecture tours and struggled with guilt and regret over having been absent when his beloved daughter Susy died of meningitis, and later when another daughter, Jean, died of an epileptic attack. In his final years, the public seemed to want Twain himself more than his books. "His image was so familiar," Shelden reports, "that it was regularly featured in advertising for everything from cigars to kitchen stoves." As William Dean Howells put it, "His literature grew less and less and his life more and more."

Twain wouldn't necessarily have resented such a characterization; he was as much a "consummate showman" as a writer, and he reveled not only in attention but also in encounter and in the conversations that provided opportunities for his ready wit to have its happy effect. Some of those conversations were about literature: he took a lively, sometimes pugnacious interest in the debates over the authorship of Shakespeare's plays, siding with those who believed that the Bard was not the author. Some were about God. Over the years he periodically made efforts to retrieve a vestige of the faith that wore thin early in his life after he took in the consistent hypocrisies of "respectable" people. He never reclaimed his faith, but even Letters from the Earth, the book in which his sharpest barbs are aimed at religion, reveals in its dark way a longing for a form of faith that would not so conspicuously undermine its own claims, and for an answer to the tormenting question of theodicy.

Some of his conversations were about astronomy, especially with respect to predictions about the return of Halley's Comet. Having been born in 1835, when the comet came within visible range, Twain predicted—rightly—that he would "go out" with it as well. More urgently, in person and in print, he took up the issue of American imperialism and the exploitation of laboring people. Though he never completely shed some of the prejudices of his Southern Presbyterian youth, he spoke out fervently against class bigotry and economic enslavement where he recognized its effects—and, famously, against war in the 1905 "War Prayer."

Though Twain is perhaps best remembered for his celebration of rural boyhood, his personal enthusiasms tended toward invention. He took a personal interest in the development of color photography, or the "autochrome" process, and invited one of its pioneers to his home for dinner and billiards. Hearing a demonstration of the newly unveiled Telharmonium, which transmitted music over telephone wires, he remarked, "Every time I see or hear a new wonder like this I have to postpone my death right off. I couldn't possibly leave the world until I have heard this again and again." Even the severe financial loss he took on the infamous and cumbersome Paige linotype machine didn't squelch his tendency to invest time, interest and, sadly, money in unproven technological novelties.

Twain invested in the next generation in other ways as well. Having no grandchildren of his own (though his daughter Clara was pregnant at the time he died), he gathered daughters and granddaughters of friends and admirers into a club he called his "angelfish." He told them stories, taught them to play cards, held musical evenings and took them on excursions. His interest was both grandfatherly and boyish; his own impulse to play directed him toward the young even in his final months.

Those months were full of pain. The death of several close friends and of his daughter Jean, increasing distance from his surviving daughter, burglary of his house, betrayal by two trusted household servants, copyright infringement and a deepening catarrh from years of heavy smoking prevented him from fully enjoying his celebrity and privilege. Shelden's point, however, is that he rose to meet that pain with a remarkable resilience that is evident even in some of his more caustic assessments of what he often called "the damned human race." Shelden offers not only thoughtful, provocative glimpses of that spirit but a reminder that the art of biography can be generous without succumbing to sentimentality and can teach compassion in the way it frames and sometimes withholds the retrospective judgments

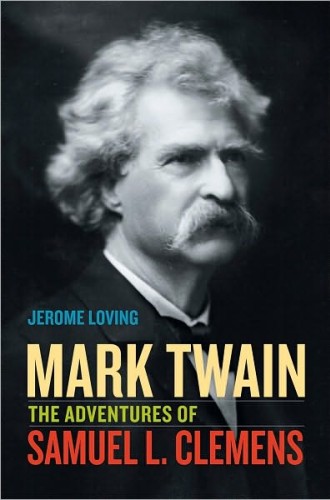

The costs of Twain's life are detailed on a wider chronological canvas in Jerome Loving's Mark Twain. In its prologue he quotes Bernard De Voto's observation that "in Mark Twain's humor, disenchantment, the acknowledgment of defeat, the realization of futility find a mature expression. He laughs and, for the first time, American literature possesses a tragic laughter." Whether Twain would describe his own life as tragic is debatable, but the long inventory of losses in this biography traces a landscape where sorrows loom like strewn boulders, giving the story its distinctive topography.

In addition to the losses of his wife, daughters and friends in later life, the early death of his father and two young siblings and, even more significantly for him, his brother Henry's violent death at 20 in a steamboat explosion, left him with grief and self-imposed guilt to which he alluded often enough to suggest that they continued to haunt him for many years. With his father's death came a decline in family fortunes that was the first of a number of financial reversals he was to weather—some the predictable result of a journalist's edgy life in the unsettled West, others the consequence of both his father's and his own poor investments.

Loving's short, sharply focused chapters give the effect of expertly framed snapshots—a form peculiarly suitable for an episodic life full of incident, dramatic moments and changes of fortune. Scene by scene, our understanding of the story's complex subject is layered in ways that deepen our grasp of the paradoxes of his character. Capable of great tenderness, especially toward his family and a few friends—like Mary Fairbanks, whom he considered a second mother—Twain was equally capable of long grudges and savage invective when offended, mostly expressed on written pages, many of which were reserved from publication until after his death. Conflicted about race relations, he could exhibit attitudes that most today would consider bigotry, even as he gave financial assistance to black students and wrote with some passion about lynching. He defended Jews from discrimination even as he perpetuated damaging stereotypes.

Richly gifted as a humorist, Twain resisted that public identity, wanting equal recognition for the seriousness and depth of thought, wide reading and general knowledge that informed even his most lighthearted works. He strove for respectability even as he flouted decorum for the sake of laughter. His work gave great pleasure and great offense, sometimes to the same audiences. In Britain, for instance, his visits were greeted by enthusiastic crowds and wide newspaper coverage—evidence of an affection he fully returned—yet A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court mocked some of the most sacred of British traditions (even approving cartoon illustrations that caricatured Queen Victoria as a hog and the prince of Wales as a "chucklehead") and triggered such outrage that, Loving observes, "it's a minor miracle Twain had any English friends left at all." A reviewer in the Pall Mall Gazette commented that "Mark Twain might as well have burlesqued the Sermon on the Mount."

Raised a "fundamentalist Presbyterian," he pursued faith questions with strange persistence, endeavoring more than once to realign himself with Christianity for Livy's sake, but he reserved some of his harshest judgments for Christians. Indeed, some of those harsh words now appear prophetic: in "To the Person Sitting in Darkness" he wrote, "Two or three centuries from now it will be recognized that all the competent killers are Christians; then the pagan world will go to school to the Christians—not to acquire his religion, but his guns. The Turk and the Chinaman will buy those to kill missionaries and converts with."

Twain's ambivalences are notorious, and they are reflected on by most of his biographers, most notably perhaps by Justin Kaplan, whose Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain makes his two-sidedness a central focus. Loving offers a nuanced presentation of Twain's character by drawing on an abundance of primary material, some of it only recently available, to enrich our understanding of the multiple pressures that came to bear upon Twain as he became a public icon. Though he retained a remarkably unpretentious candor and authenticity even in the presence of power and wealth—venturing to make jokes during an audience with King Edward VII, for example—Twain learned to guard his private life and opinions. Often in later years he relieved his frustrations by dictating unpublishable diatribes to his amanuensis and companion Paine. With the help of multiple camera angles, Loving provides in this biography a study in the astute survival strategies that enabled Twain to maintain, despite inner conflicts and public pressure, the core of humanity and humor that was his gift to the rest of us.

To Twain's contemporaries, that gift frequently took vivid and memorable form in conversations that left laughter in their wake like a blessing. For instance, with characteristic irreverence, he urged and encouraged former president Grant to complete his memoirs: "'Don't look so cowed, General,' he teased him. 'You have written a book, too, & when it is published you can hold up your head & let on to be a person of consequence yourself.'" He argued in support of Whitman's Leaves of Grass when the controversial poems were being attacked as pornography, pointing out that "such 'classic' writers as Rabelais, Boccaccio, Cervantes, Chaucer, and Shakespeare were in every gentleman's library," and adding, "Now I think I can show, by a few extracts, that in matters of coarseness, obscenity, & power to excite salacious passions, Walt Whitman's book is refined & colorless & impotent, contrasted with that other & more widely read batch of literature."

Ever unabashed by others' fame and expertise, Twain both consulted Sigmund Freud and entertained him on a trip to Vienna with a talk titled "The First Melon I Ever Stole," and he offered unsolicited advice to William James, telling him to take a course of "medical gymnastics," as he himself had, for the health of his ailing nerves. Despite many bitter observations that humankind was a disappointment and life "a swindle," Loving concludes, Twain's "towering sense of humor and profound empathy seldom failed him for long."

That these two volumes should appear simultaneously is a happy coincidence. Americans continue to read Twain, and read about him, for good reason. No one else has contributed more to our shared sense of the comic or to the myths that have, for good or ill, shaped the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves. His challenges to hypocrisy, bigotry, imperialistic presumption and abuse of power retain their relevance, his wit most of its edge, his aim its accuracy, and his best characters their capacity to mirror what we still need to see about our not-always-beautiful selves. His life story may also give us cause to realize how even the most gifted may need forgiveness—they sinned boldly by remaining faithful to their gifts.