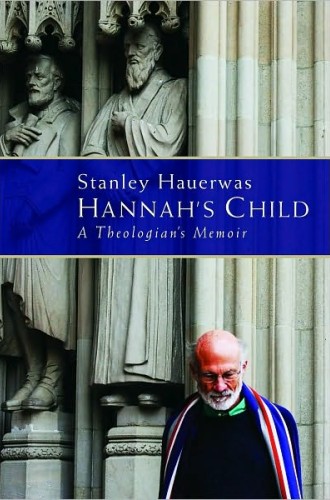

Being Hauerwas

The subtitle of Stanley Hauerwas's new book raises a question: Why would anyone want to read a theologian's memoir? The answer is not immediately self-evident. One can admire a thinker or an artist and still not be drawn to the person's life story. I once began reading a biography of Ella Fitzgerald, whose artistry I greatly admire, but I gave up about halfway through because I concluded that the most interesting part of Fitzgerald's life is found in her music.

Something similar could be said of many theologians, including important ones: what we really want to know about them is in their body of work. A memoir or biography of just about any theologian other than Dietrich Bonhoeffer would hardly be riveting. I imagine one titled Memoir of a Theologian: Tenured Professor, Department Chair, Expert in the Arcane.

But Hannah's Child is one theologian's memoir that clearly is worth reading, and for reasons that go beyond the fact that Hauerwas is a theologian of great influence. One reason to read this book is that Hauerwas's thought and his person have always been inseparable, and in ways that are not the case with many theologians. In his theological essays, he has always seemed comfortable writing in the first person and making reference to his own life. This is not narcissism as much as it is an invitation to be held accountable: Hauerwas contends that you cannot rightly consider someone's thought apart from that person's life; as he often puts it, "Only ad hominem arguments are interesting." Obviously, to write a memoir is to invite just that kind of argument.