God among the gangs of Central America

In many countries around the world, religion is often indicted as the primary force driving hatred and violence. In at least one region, though, Christian churches not only work heroically to bring peace and reconciliation, but are literally the only signs of hope. And this powerful story has been unfolding on Americans’ own doorstep.

Central America includes some of the world’s most violent societies. Among the most troubled are the nations of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, which together comprise the Northern Triangle. All these countries were shaped by the savage civil wars that swept the region in the 1980s, killing hundreds of thousands. Many residents fled to Mexico or the United States, and when they or their children returned, some at least brought with them the gang cultures they had witnessed in Southern California and elsewhere.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Central American gangs became very large and intimidating organizations, with complex rituals and bloodthirsty initiations. The most notorious network, the heavily Salvadoran MS-13, claims 70,000 members and operates in multiple countries. Because of the arsenals left behind at the end of the civil wars, the gangs are extremely well armed, and they freely use paramilitary force to advance their interests and slaughter rivals. These groups flourish in areas that offer very few legal opportunities to gain a livelihood.

Another side effect of the wars was to drive rapid and unplanned urbanization, as peasants fled a countryside that had become a free-fire zone. Since 1970, the combined population of the three countries has risen from 12 million to 30 million.

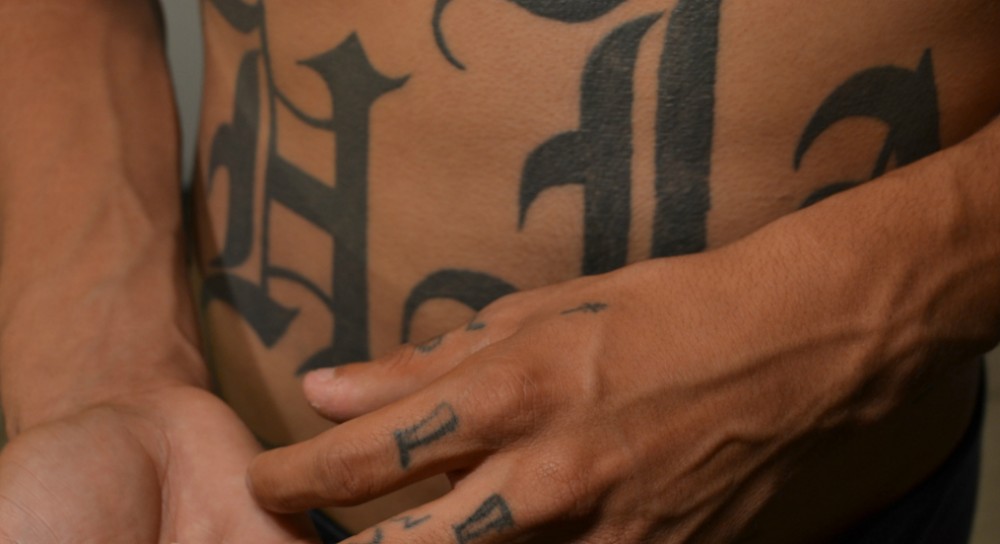

Taken together, the consequences would have been instantly recognizable to Thomas Hobbes. Lacking an effective or honest government, cities are divided on near-tribal lines. Tattooed warriors engage in acts of murder and torture. The region has the highest homicide rates for any part of the world not actually involved in war. In 2015, El Salvador’s murder rate reached 90 per 100,000, compared to 4.5 for the United States. Cities like San Salvador and Tegucigalpa are among the most dangerous places on the planet. Prisons are effectively run by the gangs, and citizens regularly respond to street crimes by lynching offenders.

In such a situation, churches find themselves on the front lines. The chaos of the past few decades stirred a powerful religious revival, in part as a rejection of the worldly ideologies that had wrought such havoc. The most obvious manifestation is an upsurge of zealous Protestant and Pentecostal churches. Guatemala has become a symbol of Protestant growth in Latin America: 40 percent of Guatemalans are Protestant, giving them near parity with Catholics.

Evangélico churches abound in the poor urban areas that also form the battlegrounds for the gangs, and here those churches are often the only functioning institutions representing the legitimate world. Day by day, pastors and the faithful witness violent battles, which they interpret as episodes of spiritual warfare.

Extensive religious interventions against violence have been discussed by several fine scholars, including Robert Brenneman, Kevin L. O’Neill, and Jon Wolseth. Together, their books show the many ways in which Christians seek to combat gangs, including seeking to prevent young people from being recruited and channeling them into paying work. Governments and international organizations fully support these faith-based enterprises, given the lack of any trustworthy alternatives.

Many church efforts involve helping people out of gang life and reintegrating them into the mainstream world. Churches play a key role here because the gangs retain some notional respect for the realm of faith. Normally there is no exit for a gang member short of death, and the only grudging exception to this “morgue rule” is when an individual claims a religious conversion that forbids him to participate in his old activities. A sizable number of former gangsters have taken this route out of la vida loca, and some become pastors in their own right. Sincere conversion is literally a matter of life and death—the new Christian believer had better let nothing suggest that he is feigning his new faith.

Extricating gang members is only part of the story. If churches hope to retain the loyalty of those former gang soldiers, they must offer them a set of unconditional loyalties and beliefs comparable to what they had known before, a new world of unquestioning brotherhood. Ritualistic gang behaviors must be supplanted by new Christian customs and folkways, with baptism replacing the old initiation rites. Even when detached from the gangs, however, defectors find it very difficult to find jobs when their bodies are so indelibly marked with the gang tattoos with which they had once vaunted their willingness to kill.

The path out of violence involves many practical problems, but these are secondary to complex psychological struggles of identity and conversion. To adapt a much overused phrase: the battle is above all a battle for hearts, minds, and souls.

A version of this article appears in the November 23 print edition under the title “God among the gangs.”