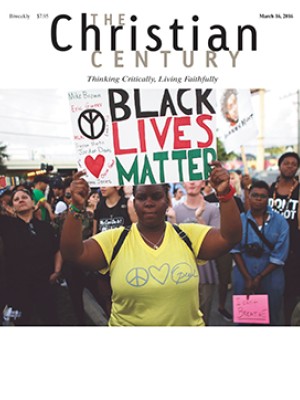

Full humanity: Black Lives Matter symposium

In the civil rights movement, language of political participation was central. BLM activists are making a more profound demand.

The Black Lives Matter movement that has unfolded in cities and on campuses across the nation is writing a new chapter in black people’s struggle for liberation. We asked writers to reflect on what the movement has accomplished, where its energies should be focused, and what implications it has for churches. (Read all responses.)

In the summer of 2015, two Black Lives Matter activists disrupted a Bernie Sanders rally. Marissa Johnson and Mara Jacqueline Willaford called Sanders to account for his position on racial justice. The largely white crowd began to boo, hurling racial epithets and ridiculing Johnson and Willaford for disrupting a cause that was intended to address the problem of poverty and for seeming to protest the candidate mostly closely aligned with the BLM platform.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

This was not the first such disruption and would not be the last as protesters across the country stopped traffic, interrupted speeches and press conferences, and refused to be invisible in the midst of America’s most recent racial reckoning.

My colleagues, especially white colleagues, expressed bewilderment about the event. “What do they want?” was the question I found myself repeatedly answering in the days after.

And this is the question, isn’t it? It’s not just a question about tactics or respectability. It is the question asked of countless protest movements regardless of their aim—whether on behalf of abolition, antilynching, the vote, or equal education. All of these protest movements were met with arguments for why direct action and protest is too radical for the moment. Even now, colleagues will ask me if I should have raised my voice or been more conciliatory in my remarks. “We have made progress after all. What do you want?” What more could you want, they might as well say.

The Black Lives Matter movement reflects a crucial reiteration of the black struggle against white supremacy. Protest movements against slavery and lynching were movements of survival that called for changes in legal frameworks to name these atrocities for what they were: violent dehumanization. In the work of the NAACP and the civil rights movement, language of participation was central. Not only should black bodies be free from exploitation and murder, they should be free to participate in the political process.

As I read and listen to BLM activists, I hear a more profound demand—the assertion of their full and unequivocal humanity. It is not a call to be more deeply embedded in or participants with the American economic or political system. It is a call for economic and political systems that will honor their inherent humanity. As an organization that makes this assertion not only in terms of race but also gender, sexuality, generation, trans, and class, BLM is an ethic, a way of being that displays its humanity and demands that that humanity be recognized. This means transformation of laws, policing, economics, and social policies. But it also means an unwavering refusal to allow white supremacy to dictate the terms of what is good for us.

In this regard, I see BLM as demonstrating a critical way forward for the ways Christians imagine their relationship to this nation and to one another. There is not a form of government or economic policy that inherently resists white supremacy. White supremacy must be overcome with persistent, strategic, and concrete assertions of our mutual humanity, working against any policy or system that dehumanizes or marginalizes another. And oftentimes this refusal does not look respectable.

As a theologian and a teacher, the BLM activists have called me to account for how my teaching and my writing resist the specter of white supremacy. Even more, their courage compels me to create in my life spaces and practices that enliven all people to recognize the present threats to our mutual humanity and fight to declare that black lives matter. Churches must ask themselves if they reflect an unqualified commitment to the full humanity of one another that is exhibited in Christ’s life and work.

BLM describes itself as “an ideological and political intervention in a world where black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression.” Is this not the church’s work, too?