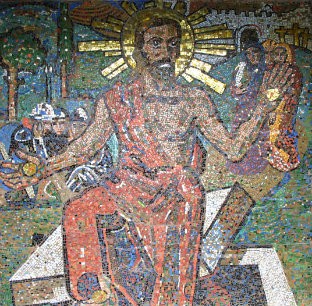

Easter’s coming

Early in my ministry I heard Bill Laws, an experienced pastor, denominational leader and mentor, say it takes a full five years to learn enough about a congregation to be an effective pastor. After five years, Bill said, your ministry begins and you will be trusted enough to do meaningful work. He was speaking at what was my first pastors’ retreat. Like others in the group of young colleagues, all of us in our first full-time positions, I was eager to get on, move up and find something more expansive and promising. We argued with Bill. Our small congregations weren’t going anywhere. We were all eager to move. Five years seemed like an eternity.

It took years for me to learn that Bill Laws was right, and so I read Martin Copenhaver’s reflection on long pastorates ("Staying power") with great interest. One year ago I retired from a 26-year ministry with one congregation, and I’m still pondering it and feeling deep gratitude for it. I experience both nostalgia and relief that I don’t have to prepare another Easter sermon. Copenhaver notes the challenge of preaching 16 Christmas Eve sermons; I recall preparing my 26th and final Easter sermon. The task seemed newly daunting, almost overwhelming. How could I preach a text that everybody had heard many times, a story many knew and held in their hearts as well as their minds?

Over the years I’ve been both comforted and amused by Reinhold Niebuhr’s confession that on Easter and Christmas he would attend a “high” church where there would be great music but little if any preaching. No preacher, said Niebuhr, is up to the task on Easter and Christmas.