Betrayal of the faithful

Lest there be any confusion, I am no relation to Jerry Jenkins, who, with Tim LaHaye, published the staggeringly successful series of Left Behind novels some years ago. These books are set in a post-Rapture world in which a heroic band of Tribulation Saints resists the overwhelming forces of the Antichrist. The appeal of the series is enormous, with some 65 million copies sold to date.

Apart from offering spectacular action scenes, the Left Behind books allow readers to imagine themselves in an alien religious world in which Christians face the threat of direct and bloody persecution aimed at forcing them to renounce their faith and accept the Mark of the Beast. Perhaps some readers are prompted to ask themselves how they might respond in such a situation. Would they hold firm or would they apostasize?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

It would be unfair to criticize Left Behind for what it is not: the series focuses on action, not theology, and it has few literary pretensions. But it is instructive to compare this distinctively North American view of persecution and martyrdom with that found in other parts of the world—places where such nightmares do not lie in the supernatural realm of the end times. For some Christians, the menace of apostasy is anything but distant or theoretical. It is something they have to consider as a serious prospect in their own lives.

One of the greatest Christian novels of the past century is Silence (1966), by the wonderful Japanese Catholic writer Shusaku Endo. Endo's work describes the horrendous experiences of Japanese Christians in the mid-17th century, when persecution all but eliminated a once-flourishing church. Many thousands of believers—European and Japanese—were forced to renounce their faith in the face of dreadful tortures.

The hero of Silence is a Jesuit priest, Father Rodrigues, who had always assumed that his faith would someday triumph and must wrestle with the certainty of failure. As he meditates, "The black soil of Japan has been filled with the lament of so many Christians; the red blood of priests has flowed profusely; the walls of the churches have fallen down; and in the face of this terrible and merciless sacrifice offered up to him, God has remained silent." How could God permit this? Why did brimstone not rain down upon the persecutors, why did God not melt their hardened hearts?

Ultimately, Rodrigues finds consolation in his vision of God not as the omnipotent King of All but as Jesus the fellow sufferer, the co-martyr of persecuted humanity.

Martin Scorsese's long-anticipated film version of Silence will appear in 2013, and already advertisements have appeared with the tag "Sometimes silence is the deadliest sound." As much as one looks forward to the film, one wonders how fully it can present the novel's harrowing spiritual dilemmas.

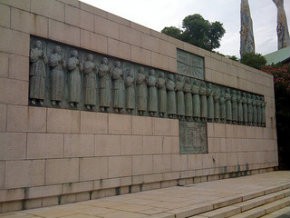

Whereas Endo looked back three centuries for his story, Korean-born writer Richard E. Kim used the events of his own lifetime in his 1964 novel The Martyred. Although this book has largely dropped from literary memory, it created a sensation in the U.S. and earned Kim a Nobel Prize nomination. (The book is now a Penguin Classic.) Like Silence, The Martyred deals with persecution and martyrdom not as simplistic stories of heroism and Christian defiance, but as messy and ambiguous affairs, in which the outcome might on occasion be failure and even apostasy.

Kim served in the South Korean forces during the war that erupted on the peninsula in 1950, during which communist North Koreans massacred Christians by the thousands. The Martyred focuses on one episode in which, reputedly, a dozen Korean Protestant pastors were murdered after resolutely refusing to renounce their faith. Naturally, both government and church wanted to exalt and publicize these native martyrs in order to galvanize Christians and other patriots in support of the war effort.

On further examination, though, it has become clear that the martyrdom scene was nothing like as straightforward as initially reported, nor were the heroes and villains so distinct. The book's most interesting character is Pastor Shin, who falsely confesses to a degrading apostasy in order to win credit for his subsequent repentance, as well as to preserve the image of the supposed martyrs. In handling such narratives, truth can be an elusive commodity.

Early Christians took apostasy very seriously as a major threat to church order. They carefully considered how the community should respond to those who abandoned their faith and even betrayed fellow believers. Although Euro-Americans can afford to treat martyrdom and apostasy as ancient history, many newer churches cannot afford that luxury.