C. S. Lewis’s Aeneid

During the early 1960s, the Christian Century published a series of answers by prominent authors to the question, "What books did most to shape your vocational attitude and your philosophy of life?" The June 6, 1962, issue featured advice columnist Ann Landers, who provided an impressively erudite list, and C. S. Lewis.

Lewis's list holds much interest, but few surprises. George MacDonald's Phantastes and G. K. Chesterton's The Everlasting Man, the two Christian books that captivated Lewis at the height of his skeptical period, receive top billing, followed closely by the great English poems of vocation, Herbert's The Temple and Wordsworth's The Prelude. Other books on the list are The Consolation of Philosophy, Boswell's Life of Johnson, Charles Williams's Descent into Hell, Arthur Balfour's Theism and Humanism and Rudolf Otto's The Idea of the Holy (a sure defense against mistaking Aslan for a tame lion).

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

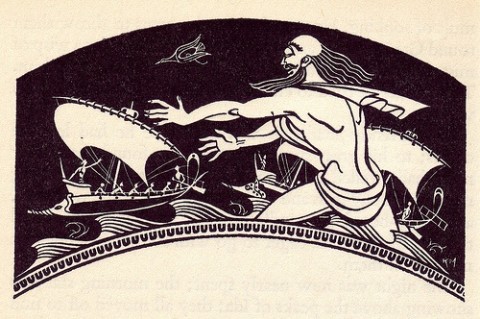

Notably, all but one of the books Lewis mentions are Christian. The one exception, the one permanent debt he records to a pre-Christian book, is Virgil's Aeneid, the epic poem in which the Trojan Aeneas, lacerated by war and Juno's wrath, travels to Italy under divine summons and lays the foundation of Rome. Long before Lewis became a Christian, the Aeneid acted upon him almost as a Christian epic; long after he became a Christian, the Aeneid remained central to his understanding of vocation. Lewis's debt to the Aeneid, already evident from his discussion of the epic in A Preface to Paradise Lost, is now more clear than ever, thanks to the publication this spring by Yale University Press of Lewis's "lost" Aeneid translation, skillfully reconstructed by classicist A. T. Reyes.

Oddly enough, the Aeneid itself was nearly lost. Virgil's dying wish was to burn his epic poem; only by the intervention of Augustus Caesar did the work live to shape the "vocational attitude" and "philosophy of life" (as the Christian Century editors expressed it) of the Roman Empire and subsequently of the Christian West. And C. S. Lewis's Aeneid would have perished in a similar manner had his brother Warren Lewis succeeded in burning what he judged to be inessential literary remains. This time it was no Caesar but Walter Hooper, Lewis's secretary and biographer, who intervened.

What survived the bonfire is the whole of book one, along with 516 lines of book two, 253 lines of book six, and a few other fragments, the fruit of some three decades in which Lewis experimented, now and again, with converting the hexameter of the Aeneid into English rhyming alexandrines: "Of arms and the exile I must sing, of yore / Guided by fate from Troy to the Lavinian shore." He renders Juno's scheme: "Leading them far, for-wandered, over alien foam / So long was fate in labour with the birth of Rome"; echoes the grim resolve with which Aeneas obeys his calling: "the mind remains unshaken while the vain tears fall"; and captures, in a couplet he would often quote, the plight of the Trojan women suspended "'Twixt miserable longing for the present land / And the far realms that call them by the fates' command." The poetic diction takes some getting used to, but Lewis felt that modern English translations of the Aeneid were too consciously "classical," too leery of concrete, archaic imagery. He attempts instead a medievalist's touch, bringing to his translation a blend of the ceremonial and the sensuous not unlike the final scenes of his Perelandra. The result should be seen as an experiment, not compared to the recent acclaimed Aeneid translations. Its chief value is in what it tells us about Lewis as a Christian reader of the pagan past.

For the Middle Ages, Virgil was an anima naturaliter Christiana, a prophet who, in his Fourth Eclogue, foretold the birth of Christ. But for Lewis, it was in changing the subject from the adolescent theme of heroism to the adult theme of vocation that Virgil prepared the way for all subsequent Christian epics. Lewis told Tolkien that he found similarities between the Aeneid and The Lord of the Rings—each one a "great and hard and bitter epic" of reluctant heroes, "men with a vocation, men on whom a burden is laid"; each one evoking a legendary past, marking a novus ordo seclorum, and foreshadowing beyond the ages of the world and the "tears of things" something very like the gospel.

"I've just re-read the Aeneid again," he told Dorothy L. Sayers, when she was in the throes of translating Dante. "The effect is one of the immense costliness of a vocation combined with a complete conviction that it is worth it," not only because of the harrowing ordeals Virgil depicts, but also because he wrote under duress, at a time of political violence, employing subjects and forms not entirely of his own choosing. "It is the nature of vocation," Lewis wrote, "to appear to men in the double character of a duty and a desire, and Virgil does justice to both."

Perhaps poetry would have more influence in our culture if it had this double character, which translation—inevitably an act of obedience as well as creative freedom—still retains. Lewis's unfinished Aeneid, however it may fare with critics, establishes beyond doubt his vocation as a translator to the modern world of its own forgotten traditions. Lewis understood the poetry of vocation, even if it was not his vocation to be a poet. That Virgil, erstwhile prophet of Christ, should speak again though Lewis, preeminent apostle to post-Christians, seems a fitting tribute.