What I knew about Jane Goodall: she was the woman who lived in Africa with apes. I could conjure an image of her from pictures I’d seen—slender, attentive, crouched with binoculars, hair pulled into a ponytail. I didn’t remember, if I’d ever known, the seismic shift in primate biology occasioned by her discovery that chimpanzees use tools. Once, in a tense family Trivial Pursuit battle, my middle-aged brain took several minutes of silent concentration to locate the mental file with her name on it. “I know her name has a g,” I said.

Then I caught the last few minutes of an interview with her, timed to promote the 2020 National Geographic documentary Jane Goodall: The Hope. A caller asked Goodall what brings her joy. She answered, “It's being out in nature, and it doesn’t have to be the forest with chimpanzees, although that’s my very most favorite. But somewhere out in nature, preferably alone.” In that moment, I felt like I’d discovered a new friend, reminding me in a gentle British accent that since the beginning of this pandemic one occupation has given me more joy than any other: sitting on the back patio, watching the animals, preferably alone.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

When the interview ended, I headed to the den in our basement and watched the documentary. I learned even more of what I didn’t know about Goodall, not least that my own observing nature has nothing in common with her early immersion in the forest. I learned that she’s a visionary and entrepreneur who now rarely gets to do what brings her joy, grasped as she was by a new vocation, a new call—call, the only word that captures the depth of her dedication and warrants its costs. “I’m always traveling, trying to save the world,” she says. “A bit of a tough job.”

When Goodall, at age 26, left England for the Gombe forest of Tanzania in 1960, she was fulfilling a dream she’d had since she read the stories of Dr. Dolittle as a child: to live with the animals in Africa. Later that year she made her seminal discovery when she observed chimpanzees stripping twigs of their leaves and then using the twigs as tools to extract termites from holes. Until then, humans were considered the only toolmaking animals. Goodall’s research challenged the very definition of what it means to be human, the idea that our intelligence makes us different in kind from apes.

The 2017 documentary Jane covered Goodall’s early career as a researcher. Jane Goodall: The Hope picks up where Jane left off, with Goodall leaving the work of primate research to become an environmental activist. In 1986, at a colloquium on chimpanzee research, she attended a session on conservation. Focused as she had been on her own research, she was relatively unaware of the decimation of the chimpanzee population from poaching and deforestation. Upon learning the plight of chimps across Africa, she became seized by what Quakers would call a concern: to use her fame to advocate for chimpanzees, indeed for all of creation; to do the tough work of saving the world. In another interview she called it her Damascus Road experience.

I use the theological language of call because Goodall uses similar language, the language of purpose. “Being the way I am,” she says, “and feeling that I have a message to give, and that I was put on this planet to do it, I have to do it. And I can’t give up.” Michael Nichols, a photographer who has traveled extensively with Goodall, captures her single-minded commitment to spread her message and her status as a cultural icon: he calls her the “Mother Teresa of the environment.”

What had I expected to discover as I watched—Jane Goodall, the passionate scientist? Jane Goodall, the introvert biologist? Instead, I was presented with a woman about whom associates use the language of sainthood; an octogenarian who has spent decades of her life as an activist and diplomat, as comfortable speaking to schoolchildren as she is to heads of state; a grandmother who traipses the globe more days than she’s home in order to continue her mission.

Watching footage of Goodall dash through an airport to get to her next engagement, her words about having been put on this planet for a purpose and with a message fresh in my mind, I thought of Jesus, who, when his disciples found him alone praying and urged him to return, said, “Let us go on to the neighboring towns, so that I may proclaim the message there also; for that is what I came out to do.”

There’s an irony in watching the story of a scientist who lived so intimately with creatures of the forest during a global pandemic likely catalyzed by the proximity of humans to animals in wildlife markets in China. As human society increasingly encroaches on what once was the wild but now is our backyard, more viral transmission from the animal world to ours is likely to occur.

But what Goodall learned in the forest and continues to preach is the truth that there is no “animal” world and “our” world—there is only the world, about which she speaks in religious terms. “Being out in the forest,” she says, “I had this great sense of a spiritual awareness, of some spiritual power. . . . You cannot help but understand how everything’s interconnected.” Later she adds, “It was the kind of feeling that I sometimes have in one of the old cathedrals where people have been to worship year after year after year.” This ecclesial image of communities at worship, hallowing a sacred space, informs the telos of her ecological spirituality: the unholy human degradation of the nonhuman creation must yield to holy co-flourishing. I find Goodall’s refusal of a materialistic reductionism refreshing, however much the theologian in me wants to quibble with her vague spirituality.

Of course this message is not new. Sixty-five years ago, Rachel Carson wrote that, wading into the ocean, she senses the “intricate fabric of life by which one creature is linked with another, and each one with its surroundings.” Wendell Berry has long promoted a vision of ecological interdependence. Novelist Barbara Kingsolver has taken up the mantle, as have so many others. And theologians like Norman Wirzba are narrating ecological concerns in the distinctive language of Christian theology.

But none of them has had Goodall’s global platform and influence. And given that human beings seem incorrigibly hostile to this reality, for me to quibble over her nature mysticism or the unoriginality of her message seems beside the point, even small-minded.

Goodall’s holistic vision has supported the mission of her entrepreneurial efforts. The Jane Goodall Institute, founded in 1977, began working in the early 2000s with Tanzanian villages near what remained of the decimated Gombe forest. Goodall learned that the institute’s chief concern, deforestation, wasn’t shared by villagers, who worried about health care, education, water—their own survival. Only when she listened to their concerns, rather than preaching hers to them, were the institute and the villages able to discover together what a harmonious kinship between the Gombe forest and Tanzanian villages could look like—community-based conservation, they call it. From satellite images, for instance, villagers learned how deforestation contributed to mudslides and how forest conservation and sustainable use of its resources could benefit the villages. Now villagers themselves volunteer to patrol the forest, looking for animal traps and reporting illegal logging. More recent satellite images prove the results: the forest is regenerating.

Goodall’s ecological mind-set also shapes the way she engages with those who might be considered her adversaries. She has been criticized for her approach to politicians, oil companies, and medical labs that perform research on chimps. Animal rights activists protested her visits to NIH-funded laboratories. Environmentalists questioned her working with the Conoco oil company to build a chimpanzee sanctuary in the Congo. But Nichols defends her approach: “What’s Jane Goodall doing working with the ‘bad guys’? Well, that’s what you do if you want to make change. You don’t work with the choir. You work with the bad guys, and they become the good guys.”

It’s an approach she teaches to children and young adults in another of her entrepreneurial ventures: Roots and Shoots, an environmental education and empowerment program, founded in 1991, that has worked with millions of children in hundreds of countries. “Don’t be confrontational,” Goodall tells them. “Reach people’s hearts to change their minds.”

Except for the fact that Goodall is a global celebrity, I question the “Mother Teresa of the environment” label. I notice more parallels with another religious figure: Dorothy Day, and not just because Goodall’s silver ponytail is as familiar as the coiled silver braid so often photographed atop Day’s head.

In Goodall’s pining for the solitude of the forest, even as she’s brewing coffee in a hotel room—she always reuses her coffee grounds—and toasting bread on the hotel iron, I glimpsed something of Day’s desire to be with her Catholic Worker family even as she boarded bus after bus to protest and speak across the country, travel that took a toll on her health and which friends encouraged her to quit. Throughout Jane Goodall: The Hope, friends urge Goodall to slow down. “Do I enjoy the life I’m leading?” she asks. “Actually the answer is really ‘no,’ because I’m traveling 300 days a year or more, every year since 1986.” Mother Teresa never knew what it was like for a mission to call her away from her own children and grandchildren, to so definitively disrupt the life of a family. Dorothy Day did.

The documentary is largely silent on Goodall’s family life. We see that her grandchildren delight in her twice-yearly visits. (She lets them join her in her nightly glass of whiskey, even the ones under 21.) Still, despite their praise of her, there’s a formality in their relationship, evident in their referring to her as “Jane.” Her son, Hugo “Grub” van Lawick, is interviewed for about 20 seconds, long enough to suggest that anger drives her passion, though her words and demeanor lack any hint of anger. They are shown greeting each other with a stiff hug. He asks her if she’d like tea or coffee, as if meeting a stranger. What’s the backstory here? I wondered.

So the next night, I returned to the basement couch, this time joined by my 15-year-old son, and watched Jane, the documentary that explores Goodall’s early life.

When her discovery of chimps making and using tools made Goodall famous, National Geographic sent filmmaker Hugo van Lawick to document her work. Hugo and Goodall eventually married, and they had a son, Grub, whom they raised in Africa. Hugo needed to be in the Serengeti to make films, and he wanted Jane to be with him, but she knew her work was to research chimpanzees; she wouldn’t leave her larger primate family. They eventually divorced, though they remained close.

Goodall tried to homeschool Grub, but it became clear to her that he needed a school in England, so she sent him to live with her mother, and he rejoined her in Africa during the summers. This story reminded me of how Day was often criticized for trying to raise her daughter, Tamar, in a Catholic Worker house. Tamar was sent from boarding school to boarding school, never receiving an education commensurate with her potential. The strain her mother’s devotion to poverty put on their relationship stands out in recent biographies of Day.

Given the lacunae in the new documentary, I wondered if some of the same tension might have been present in Goodall’s relationships, or if the life of an activist was taking its toll on her, a natural solitary, as it had on Day. There’s a hint of sadness in her own voice, even regret, when she admits how she rarely sees her grandchildren. And there’s the often repeated refrain in the film that her true love is the forest, and solitude, and living with the chimpanzees. If being an activist is her vocation, she’s contradicting Frederick Buechner’s famous definition of vocation—her work might meet the world’s great hunger, but it doesn’t touch her own deep gladness.

Though the documentary is largely laudatory, it displays the inherent costs of such a life, as if to say, here’s what’s possible when a concern grabs you so completely—hundreds of nights in hotel rooms, countless hours on airplanes, distance from family. When I hear Goodall say, “The kind of life I’m living now is completely crazy, and there are times when I think I cannot go on like this,” I have to ask: Is this a life to praise, to hold up as exemplary?

In a telling scene near the end of the film, Goodall is sitting at the kitchen table in her family home in Bournemouth, England, with Mary Lewis, vice president of the Jane Goodall Institute. Papers are spread on the table as Lewis flips through pages listing upcoming travel engagements. As Lewis reads Goodall’s commitments, Goodall says, “You’re making me feel ill,” then removes her glasses and wearily rests her face in her hands, her long, slender fingers hiding her eyes.

In the following scene, Goodall tells how over the years she’s wondered whether she should slow down. She describes a box she made as a child, filled with hundreds of tiny scrolls, a Bible verse printed on each one. On three separate occasions before traveling, her sister Judy offered her the box, and each time she drew at random the same verse, a saying of Jesus from the Gospel of Luke: “No one who puts a hand to the plow and turns back is fit for the kingdom of heaven.” So off she goes, suitcase in hand once more.

Since one of Goodall’s goals is to inspire the young, I decide to watch the documentary again and ask my ten-year-old daughter to join me. She sits cuddled next to me on the basement couch, her stuffed dog Boo in her lap.

Lately so many of our dinnertime conversations revolve around the pandemic, systemic racism, and a presidential administration that has exacerbated both. The word evil gets bandied about in these conversations a good bit. And we’ve hardly had time to discuss the climate change that’s rushing toward us. In the midst of all this, I want her to see someone who has spent a lifetime fighting insurmountable odds with the weapons of resolve, passion, and hope. Knowing my daughter, I suspect she will be smitten with Goodall, but we can’t control what takeaways children will absorb.

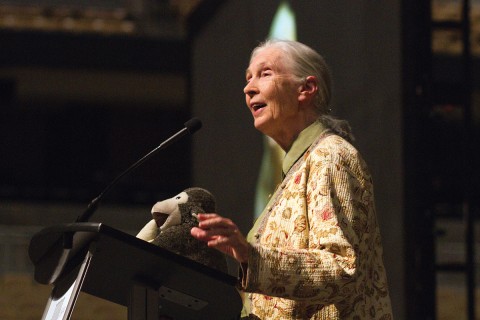

The documentary opens with the 85-year-old Goodall running around to get warm before a speech, a scarf patterned after the wings of a monarch draped over her shoulders. She walks onstage with a stuffed chimpanzee in her arm, a menagerie of other stuffed animals on a table to the right of the podium. She greets the audience, mimicking a chimp. “That just means, this is me, this is Jane,” she says.

“She looks fun,” my daughter says, already a convert.

Though it’s late and she’s tired, my daughter sits attentively to the end, edging forward during the final segment. As Goodall walks the aisles of the Norwich Cathedral in Norwich, England, city of another famous solitary, we hear her speak these words:

I was asked the other day, what’s your next adventure? What’s my next adventure? So I said, “Well, dying.” . . . I happen to believe there’s more than just this one physical life. I haven’t the faintest idea what else there is, but if that’s true, then what greater adventure can there be?

This ending underlines the perspective of wonder, curiosity, even faith (though that word is never used) woven through Goodall’s story. But the images of her speaking to filled pews in the cathedral, then wandering the cathedral alone, capture the uneasy and perhaps unresolvable tension between the two halves of her life: her frantic public life and her truest joy—to dwell in the great cathedral of the forest with the animals, but otherwise alone.

“She inspires me,” my daughter says when it ends. “She makes me want to do something, to make a difference. I feel it right here,” she says as she puts her hand over her heart.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “St. Jane?”