The United States owes King George an apology

The signers of the Declaration of Independence accused the king of crimes against the people they represented. Those very crimes have become commonplace during Trump’s time in office.

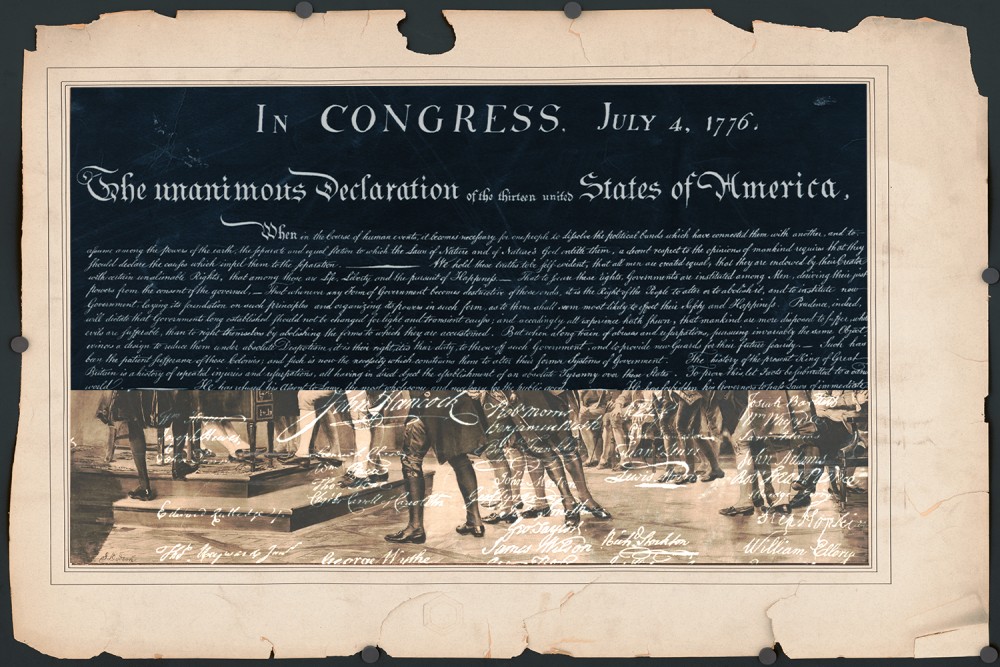

It was a revealing moment: in an interview with Terry Moran of ABC to mark the first 100 days of his administration, the president of the United States was asked about the framed copy of the Declaration of Independence hanging in the Oval Office. “What does it mean to you?” Moran asked, in the softest softball that has ever been lobbed over a presidential home plate.

“It means exactly what it says,” Trump said. “It’s a declaration of unity and love and respect. And it means a lot. It’s something very special to our country.”

Certainly any schoolchild, particularly of Trump’s generation, could be expected to be able to call up something about the Declaration of Independence. That it declared independence from Great Britain, for one, and thus inaugurated the national history of which Trump and his enthusiasts are always insisting we must be knowledgeable and proud. That it contains a pithy statement of “truths” that its framers found to be “self-evident,” that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.” Most famously, among these were held to be “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

One might view this as a peculiar sort of national humiliation, like a pope confessing that he doesn’t really know what Peter the apostle did. A foundational document becomes, in real time and at the highest level of our government, forgotten lore. But it’s not just that Trump, surely the person most completely ignorant of any aspect of American history or law ever to occupy the office of the presidency, doesn’t know the first thing about the Declaration of Independence. It’s that the very crimes and oppressions of which the signers accused King George III in the Declaration’s text have become commonplace during Trump’s time in office. Perhaps we owe King George an apology.

I admit it had been a few years since I’d read the full text. Like many people who have absorbed progressive narratives and assumptions about US history, I viewed this unread classic with a sense of irony and critique. Jefferson, that slave-owning rotter, surely had his own grubby interests hiding under all that high-flown prose about rights. And if we know nothing else about those unalienable rights, it’s that they were not even on paper or in principle ascribed to women, the enslaved, or Indigenous people.

But the Declaration makes for a bracing and eye-opening read today. Among the abuses for which King George stood accused: forbidding governors to “pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance” (one thinks here of numerous attempts to coerce states and cities into conforming to Trump’s policy preferences); obstructing “the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners” (the attempt to overturn the Constitution’s guarantee of birthright citizenship by fiat comes to mind); refusing the establishment of judiciary powers and making judges “dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices” (calling to mind constant attacks on judges, attempts to remove their jurisdiction, and the flouting of district-court rulings).

The Declaration prefigures the DOGE campaign of internal government spoliation (“He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance”), the abuse of civilian-military relations by calling the Marines and federalized National Guard units to suppress peaceful protests and conduct immigration enforcement (“He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power”), the exorbitant use of tariffs (“cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world”), new policies of unlawful detention (“depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury”), and even deportations to foreign prisons (“transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences”). And in a sense, the US president is more to be blamed for having “excited domestic insurrections” than the king was, because the latter was accused of encouraging entirely justified slave revolts, not attacks on the electoral process.

Whatever their many flaws, the people who signed the Declaration were attempting to be loyal to a principle (admittedly very English) of a sovereign government bound by law. As William Pitt the Elder vividly put it, “The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the forces of the Crown. It may be frail—its roof may shake—the wind may blow through it—the storm may enter—the rain may enter—but the King of England cannot enter!” This principle, embedded in the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution, is also out of favor today. The Trump administration claims the right to enter homes without a warrant to enforce immigration law, under color of the 1798 Alien Enemies Act. It has become shockingly routine for federal agents to accost, arrest, beat, or break into the homes of people while wearing masks and covering badges, in behavior indistinguishable from criminal gangs or the functionaries of a police state.

While executive overreach and the “imperial presidency” are nothing new, what we have witnessed in the last nine years, and particularly in the last few months, is a daringly straightforward attempt to redefine the state by making the presidency an office unbound by any law whatsoever. From withholding congressionally appropriated funds to handing out the personal information of Americans to private actors to punishing individuals and institutions without trial—all of which are now surrounded by a high wall of legal immunity granted by the Supreme Court—the American presidency is granting itself power beyond the ambitions of any pale, bewigged Hanoverian monarch.

But it’s not just at the level of state power that today’s America seems far distant from the vision of lawful liberty laid out in 1776. Something just as important is at risk of ebbing away as well. That our founding, for all its hypocrisies and imperfections, begins with an idea of universal human equality and inalienable rights is an enduring consequential fact. We fought a whole Civil War over it, as Lincoln explained when he quoted the Declaration at Gettysburg. We were to be a nation “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

This conception and dedication are under direct and explicit attack. Today’s would-be heirs of Lincoln claim the US as just another “nation-state,” a country founded and nurtured not on the premise of universal human rights and equality but on blood and soil. That we are just another “homeland,” in J. D. Vance’s peroration at the 2024 Republican Convention, just another “group of people with a shared history,” like all the places my own ancestors decided to leave. It is probably not a coincidence that the “idea” or “creed” of America is being defined out of our history at the very moment it is being disparaged in practice.

But the ideas are still good. They can still stir the soul. And our devotion to them, as Lincoln put it, can still be the difference between a brilliant, evolving American experiment and a short, brutal trip down the road ordained for all squalid fiefdoms. This Independence Day, these ideas are in need of remembering, along with the king who prompted their first articulation. I’m glad we got rid of him. But he could have been worse.