Trump’s artificial images

The AI-generated meme is this administration’s house style—moral degradation made visible.

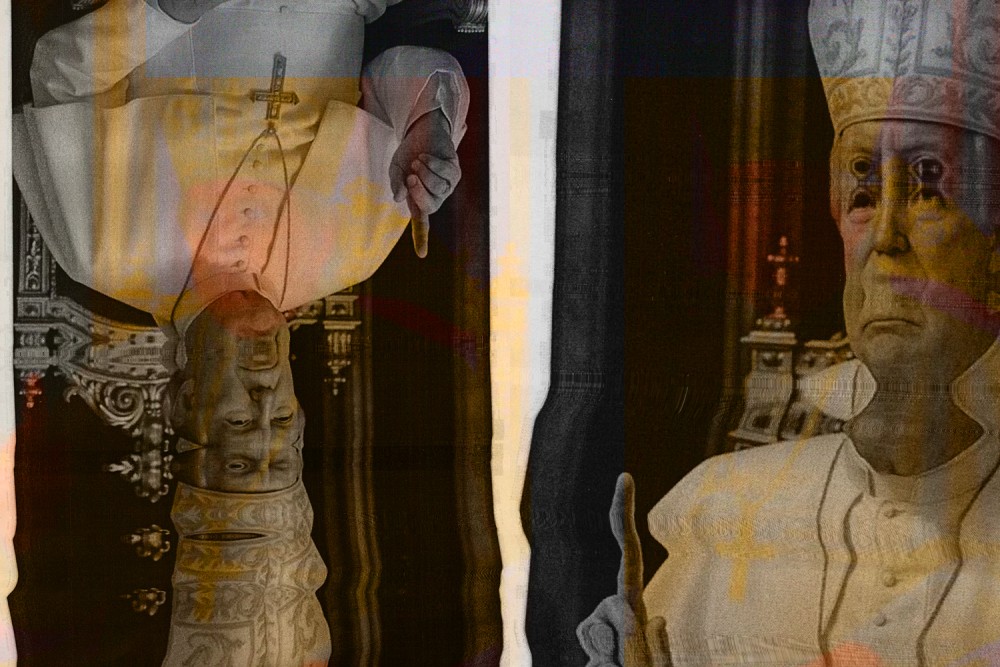

The official White House account on X posts AI memes nearly every day, ranging from the almost sort of funny (Trump as pope) to the wearily didactic (a mockup of the Obama 2008 campaign poster by Shepard Fairey that replaces the word “HOPE” with “ILLEGAL ALIEN CHILD RAPIST FOUND AT MASSACHUSETTS DAYCARE”) to the morally repulsive (an image of an ICE agent arresting a sobbing woman, rendered in the style of the Japanese animated films from Studio Ghibli). AI-generated memes are to this administration what the collective ecstasy of the rally and the defiant tackiness of the MAGA hat were to the first: the house style that determines the tone of national life.

In his 1981 book The Kennedy Imprisonment, Garry Wills reflected of John F. Kennedy’s curious combination of dazzling stylishness and political vacuity. No one could really say what exactly JFK stood for, but everyone could agree he had style. According to Wills, this was a deliberate strategy, a politics of presidential style. For the courtiers of Camelot, style was politics. “In this view,” Wills writes, “presidential style not only establishes an agenda for politics but determines the tone of national life. The image projected by the President becomes the country’s self-image, sets the expectations to which it lives up or down.”

The tone determined by the Trump administration’s AI memes is shrill and cruel. The images seem to call forth the violence they depict. By the time the ICE image was posted, the Studio Ghibli meme was already stale. AI image generators make the life cycle of a meme grow shorter and shorter, so the archive of violent images from which the next meme can be extruded must expand faster and faster. The images ask us to deepen our craving for violence, inviting us to see the suffering of another person as simply raw material to be processed into the microsecond of numbed enjoyment we get from scrolling past a meme on the way to the next one. To rework Wills a bit: The AI meme posted by the President becomes the country’s self-image, sets the expectations to which it lives down.

The moral degradation made so visible in the presidential style of the AI-generated meme seems connected to the more literal degradation inherent in the very function of Large Language Models (LLMs) and AI image generators. LLMs like ChatGPT and AI image generators like Midjourney, explains the writer Ted Chiang, work sort of like making a blurry photocopy of all the information on the internet. To produce a given line of text or a given image, AI models trawl all of the words and art created by human beings and then serve it back in a slightly degraded form. The problem is that, as a higher and higher percentage of the internet is made up of AI-generated text and images, the dataset becomes more and more degraded. The clarity leaches away each time the model runs, like making a photocopy of a photocopy of a photocopy.

In addition to this informational corruption, AI also has more materially corrupting effects. Each query to ChatGPT uses as much energy as leaving a lightbulb on for 20 minutes, and Microsoft’s carbon emissions have increased by almost a third since the company began building new AI-focused data centers. The earth itself is being degraded by AI, as about two-thirds of new AI data centers, which use massive amounts of water to cool their servers, are built in areas already experiencing acute water shortages. This is to say nothing of the destructive potential of AI-powered weapons, seen most horrifically in the Israeli military’s use of AI to automate its attacks on Gaza.

The cruel AI memes embraced by the Trump administration are evidence of a profound moral rot, and I don’t think that moral degradation can be easily disentangled from the degrading effects AI has on information and on the earth. The corruption all hangs together.

I believe Christians should take a critical stance towards AI as dangerous to our moral, intellectual, and material lives, and I believe the history of theology pushes us towards such a critical stance. AI models have no real existence of their own; they move through the world as a pale mimicry of genuine creativity that corrupts the intellectual judgment, the moral discernment, and even the material existence of that which it encounters. Theologians have for centuries had a word for this kind of corrupting and parasitic non-being. That word is evil.

I’ve argued before that we can make sense of our political reality by returning to the unfashionable theological language of the demonic, and when it comes to AI, I think we should do the same with the language of evil. It might sound hyperbolic to call AI evil, but stay with me. Theological analyses of evil can help us understand how a technology that works by emptily mimicking real human creativity can have such deleterious effects not only on thought and art, but on our morals and even the world itself. One thread of theological reflection on the problem of evil I’ve found helpful for thinking about AI is the argument, stretching back to at least St. Augustine in the fourth century, that evil does not exist.

The basic contour of the argument is that God created the world and pronounced it good, so everything that exists must be good. Evil must not be thought of as some “thing” that exists out there, but as a name for the negation or corruption of what does truly exist, roughly similar to how darkness is the negation of light or cold is the negation of heat. In his chapter “God and Nothingness” in the Church Dogmatics, Karl Barth describes evil as, properly speaking, nothing. Evil, Barth writes, has “only the truth of falsehood, the power of impotence, the sense of non-sense.”

For Barth, though evil does not strictly speaking exist, it “has its own dynamic.” This dynamic is one of imitation. This idea of evil as an imitative nothingness is where I’ve found Barth particularly helpful for thinking about the dangers of AI. The real world of creation, and also the things we creatures create like art and thought—these all exist and, as existing, are good. Evil, in Barth’s analysis, is a false imitation of the acts of God and God’s creatures; it “plays at creation and redemption, providence and dominion.” Barth’s judgment on this mimicry is decisive: “All falsehood!”

If Barth is right that evil is the empty imitation of truth, power, sense, and creativity, then it might not be beyond the pale to call AI evil, overblown as that might sound at first. AI is not genuinely creative; it is a mimicry of creativity that functions by scooping up everything humans have labored to create (visual art, literature, music, film, encyclopedias, recipes) and spitting out a facsimile. To be fair, there are times when pale imitations of creativity can be useful and even beneficial: modeling protein folding, for example, a rote and time-consuming task for biologists, has benefitted enormously from AI’s ability to generate huge numbers of models with good-enough accuracy. Who knows how many lives will be saved by research enabled by AI-generated protein models, and the moral danger of this use of AI as a brute tool for performing impossibly large calculations seems minimal. The moral risks come from the use of AI in the realm of creativity itself—art, education, thought—where AI can only mimic and degrade.

We’re already seeing these risks come to fruition. In a poll conducted not long after ChatGPT launched, as many as 90 percent of college students admitted to using AI to summarize their readings and write their assignments for them. In the Trump administration’s enthusiasm for cruel AI-generated memes, we can see the effects that AI “slop” can have not only on our environment and our intellectual life, but on our moral bearings as we try to navigate a shared national life. We live in a perilous moment when more and more people are voluntarily giving up their capacity to read, to create art, to think critically, to judge morally, all to a computer program that “exists” only by mimicking and degrading those same faculties. That this corrupting nothingness has become presidential style portends a dark future for our national life.

In his discussion of the nothingness of evil, Barth decries “the mimicry of nothingness—the play of that which is absolutely useless and worthless, yet which is not prepared to allow that this is the case, but pretends to be vitally necessary and of supreme worth.” In this moment when the White House is crawling with AI boosters eagerly pushing the vital necessity and supreme worth of their products—selling AI teachers, AI filmmakers, AI therapists, AI weapons—I believe we should not be embarrassed to dust off unfashionable language from theological history and call all this evil.

Thankfully, Barth has good advice for how we should treat evil. “Distaste is the only possible attitude.” It’s time for Christians to refine our distaste.

********************

The Century's Jon Mathieu speaks with Mac Loftin about artificial intelligence.