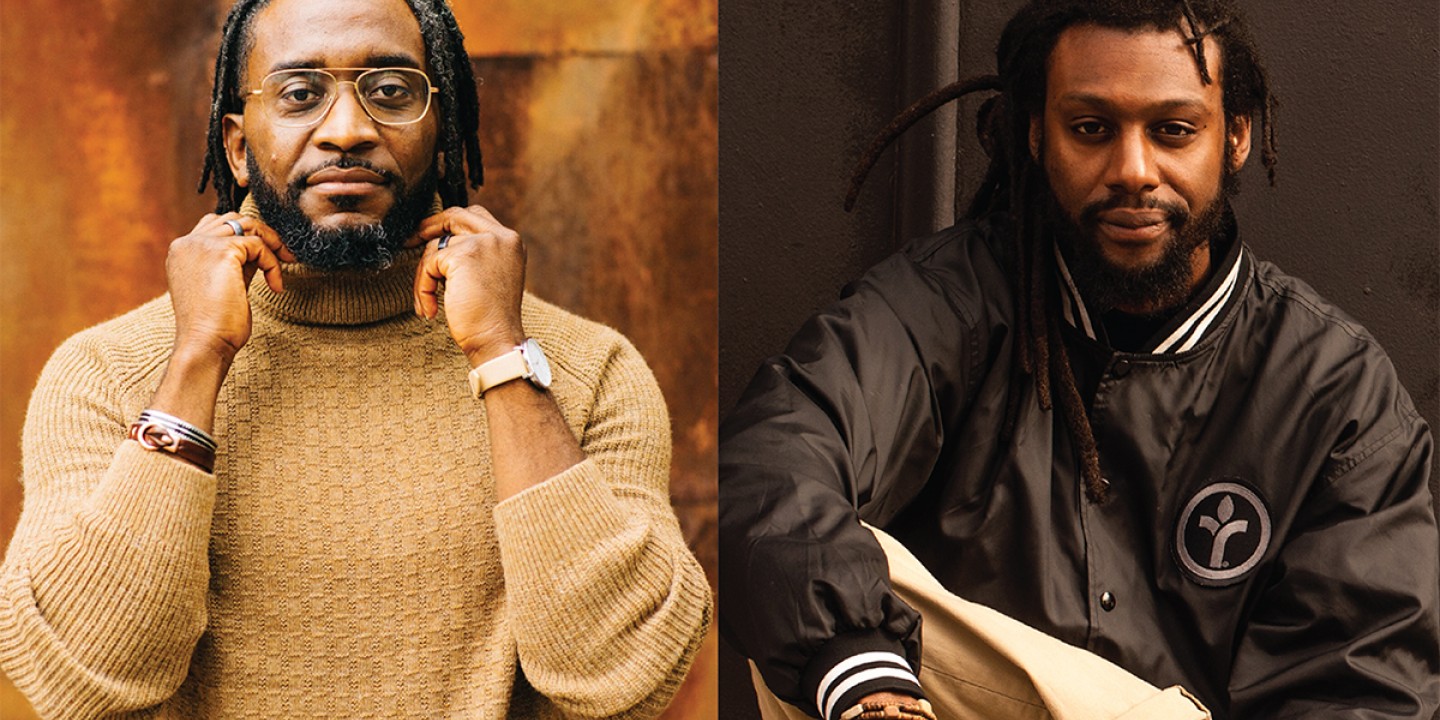

Hip-hop artists Sho Baraka and Propaganda flip the script

Stanley Hauerwas says good theological writing makes the familiar strange.

The scratch is a sound. As a technique, hip-hop artists scratch by moving a vinyl record back and forth by hand. Scratching interrupts the steady movement of the record and produces endless timbral and rhythmic possibilities. The scratch radically transformed the turntable into a musical instrument capable of deconstructing recordings and squeezing out new sounds through speakers. Hip-hop artists use turntables to tinker with timbres and make music. Ever since it was first introduced by DJs in the 1970s, the scratch has been a hip-hop hallmark.

The scratch, however, is more than a musical technique. It is more than a sound. It is a moment of rupture, a purposeful interruption breaking into the music and the moment. It is a hip-hop value.

In his book Digital Griots: African American Rhetoric in a Multimedia Age, Adam Banks describes the impact of the scratch. “It is difficult to overstate just how much the scratch changed music,” he writes, “how crucial it was to the brash announcement that Hip Hop did indeed come to change the game and even attempt to change the world.”

Like the scratch, hip-hop aims to rupture the status quo. Hip-hop began as an expression of the dispossessed, an artistic form of opposition in impoverished neighborhoods. From the beginning, the genre refused to underwrite the sentimentalities of society. Rather than reinforcing existing cultural narratives, hip-hop artists subvert the familiar.

This flipping of the script can take a number of different forms. Unique spellings, semantic inversion, and community-specific language are small ways that hip-hop flips the script. On a broader level, hip-hop artists subvert the familiar as they rap about raw, real, and troubling topics that are often ignored in mass media.

Hip-hop has also flipped the script on Christian music in surprising ways. The genre has an increasingly complex relationship with the Christian faith—the labels of “secular” and “Christian” hip-hop music are no longer tenable. For example, popular artists such as Kanye West, Kendrick Lamar, Chance the Rapper, and NF publicly profess to be Christians and rap about explicitly Christian themes. Yet these artists are signed to secular labels, rap about a very wide range of topics beyond religion, and largely reject the moniker “Christian artist.”

Amisho Baraka Lewis, who performs as Sho Baraka, has personal experience with rupture. He began his hip-hop career with gangsta rap in Southern California. After a conversion experience in college, Baraka briefly abandoned hip-hop, thinking that the genre could not be reconciled with the Christian faith. Eventually, he decided that it was possible to be a Christian and pursue his work as a hip-hop artist. Although he name-drops Augustine and Bonhoeffer in his songs, Baraka prefers not to be labeled as a Christian artist. Instead he sees himself as an artist whose beliefs and worldviews influence his work.

His lively track “Kanye, 2009,” with Jackie Hill Perry and Jamie Portee, from his 2016 album The Narrative, begins with classic gospel piano and a church choir. Suddenly this familiar sound is interrupted by a scratch as the music abruptly changes:

This scratch is followed by words intended to interrogate the status quo:

You better watch your mouth.

I’d rather pray for forgiveness for what might come out . . .

We need Black-owned and less bad loans,

Less pawn shops and liquor stores and We Buy Gold.

And why Black history always starts with slavery,

So even when I’m learning they still putting them chains on me?

This is typical of Baraka’s work. He dismantles an array of widely accepted social narratives. He flips the script on scores of different topics: the KKK and Kanye, police and politics, theology and Tuskegee, racism and religion, Whole Foods and the hood. Nothing escapes Baraka’s prodigious lyrical critiques.

Baraka’s 2020 single “Their Eyes Were Watching” draws its name from Zora Neale Hurston’s classic novel, in which the protagonist struggles to establish an authentic and uninhibited voice:

Over four studio albums, Baraka has established his own authentic and uninhibited voice. Maintaining that voice in the face of opposition, however, remains a challenge. For example, even though Baraka is known as a Christian hip-hop artist, The Narrative was pulled from the shelves of some Christian retailers because the word penis is included on one of the tracks.

When Baraka subverts an established narrative, it’s a conscious decision. On his track “Piano Bars,” from his 2017 album The Narrative, Volume 2—Pianos and Politics, he raps,

I don’t care, my dude, I don’t trip.

I just walk through your park kicking down your monoliths,

Decolonize the gospel then express it through my vocal cords . . .

Denmark Vesey getting heavy, some may call him the aggressor,

He’s moving between thugs and seminary professors . . .

The bottom line is he is changing the narrative.

Oscillating between thugs and seminary professors, Baraka aims to change the narrative through hip-hop. His verbal dismantling of monoliths, however, leads some to dismiss Baraka as nothing more than an aggressor seeking to foment agitation. These critics miss the importance of interrupting the status quo in order to find new and better ways forward.

Another hip-hop artist who flips the script is Jason Petty, known by the stage name Propaganda or Prop. He got his start nearly two decades ago with an underground Christian hip-hop group called Tunnel Rats. Since then, Prop has released several of his own studio albums and collaborated with many other artists. He describes himself as a poet, political activist, husband, father, academic, and emcee.

Over the years, Propaganda has developed an adroit ability for undermining the familiar. For example, on the track “Crooked Ways” he raps,

Native American students forced to learn about Junípero Serra,

How is that fair, bruh?

Some heroes unsung and some monsters get monuments built for ‘em,

But ain’t we all a little bit a monster? We crooked!

Prop flips the script on multiple levels here. He questions why some heroes are unsung while other, less heroic figures remain immortalized through statues. But he further problematizes the issue by saying that we are all monsterish and crooked. For Christian theology, this is a key point. Crookedness is not something that belongs to others; it is something everyone has to grapple with.

Intersections abound in Prop’s music. His music is a lyrical loom interweaving disparate topics including parenting and education, gentrification and Los Angeles, Andrew Jackson and Nelson Mandela.

This should be no surprise, since his own life is interlaced with numerous junctures. “I grew up in an almost 100 percent Latino space,” he told me in an interview. “Living in an almost entirely Brown community, you pick up on what’s different, but also what’s similar. . . . And you start noticing that power is crushing you the way it’s crushing me; it’s different, but we’re both being crushed by this, and we’re both finding solutions. . . . I didn’t have to go hunt for those worlds colliding.”

Collision often causes rupture. Drawing on his lived experience, Prop dismantles familiar narratives and invites listeners to reconsider untested assumptions. His music subverts sentimentality with a dose of dissonance.

Yet themes of connection and empathy are also prominent in Propaganda’s music. “You’re not a fully developed person if you can’t understand empathy and see your connection with your fellow human, whether you know them personally or not,” he said. “I want to spur on that ability to see yourself and see our connections. We are distinctly different, but that doesn’t mean we can’t be connected.”

Like Baraka, Propaganda is conscious of the fact that his music challenges the established narrative. On the track “Andrew Mandela,” also from Crooked, he raps,

I take shots at your sacred cows.

I dance with skeletons in closets.

I point at elephants in the room

And make a mockery of heroes.

Sho Baraka and Propaganda embody the hip-hop scratch. They rupture, subvert, and problematize that which has become familiar and comfortable for many hearers. Their aim is to make good hip-hop.

But they are also making what Stanley Hauerwas might call good theological writing. In The Work of Theology, Hauerwas explores how to produce a well-wrought theological sentence. Such a sentence “does its proper work,” he writes, “just to the extent it makes the familiar strange.”

Hauerwas argues that bad theological writing affirms the untested assumptions of the way things are in the world. Poorly wrought theological sentences offer audiences nothing more than saccharine sentimentalities about God and commonplace assumptions based on the logic of the world. For example, Hauerwas asserts that one bad theological sentence is, “I believe that Jesus is Lord, but that is just my personal opinion.”

Good theological writing refuses to underwrite the sentimentality of the world. Instead, it accentuates the stark peculiarities of the Christian community living in light of the resurrection of Jesus. Hauerwas offers a sentence from Robert Jenson as an example of a good theological sentence: “God is whoever raised Jesus from the dead, having before raised Israel from Egypt.” Instead of confirming the familiar, Hauerwas argues, this sentence forces readers to question their presumption that they know who God is prior to how God has made himself known.

In other words, good theological writing stirs synapses and forces one to think. A well-wrought theological sentence goes beyond the world’s commonplace assumptions and employs the peculiar grammar of the biblical narrative.

Sho Baraka and Propaganda fit securely, if strangely, within Hauerwas’s definition of good theological writing. Hip-hop has never been satisfied with leaving the familiar intact; it strives to make the familiar strange. On the track “Maybe Both, 1865,” Baraka raps,

Jefferson and Washington were great peace pursuers

But, John Brown was a terrorist and an evildoer

Oh yes, God bless the American Revolution

But, God ain’t for all the riots and the looting

Baraka challenges the disparity between the legacies of Jefferson and Washington and that of John Brown. He also implies that the American Revolution might have looked a lot like rioting and looting through British eyes. Agree with him or not, Baraka’s lyrics have the ability to make you stop and think.

Propaganda is explicit in his attempt to create discomfort: “It’s only strange to the comfortable. And your comfortability was built on the backs of suffering people. For the rest of us it’s not strange. This is our lived life, and it’s strange to me that you can’t see that.”

These hip-hop artists likewise resist sentimentality. “If I play to your sentimentality—if I play it safe—then I’m just going to continue what’s happening. And what’s happening is not working for all of us,” said Propaganda. “My music isn’t safe. I’m not concerned about being safe, but neither was Ezekiel or Jeremiah. These dudes weren’t safe. This wasn’t for the whole family. These prophets weren’t minivan radio stuff, this wasn’t the Disney Channel. . . . I don’t make Disney Channel stuff, and your life ain’t the Disney Channel.”

The scratch only takes a moment to perform. Yet it prophetically announces a new moment, a script flipped, a rupture in the narrative. It takes a moment to perform but a lifetime to perfect.

Well-wrought theological sentences also take a lifetime to perform, writes Hauerwas, because they require the cultivation of “a soul capable of seeing through the sentimentalities we use to hide our mortality from ourselves.” Writing a good theological sentence—inserting a purposeful scratch in the world’s familiar rhythms and rhymes—requires a lifetime of being captured by the narrative of scripture and the peculiarities of Jesus.

Like good theological writing, creating good hip-hop requires a soul capable of seeing through the sentimentalities of this world. But Propaganda is “not doing this hip-hop for the purpose of communicating good theology,” he said. “I just want to make good hip-hop. I am participating in it because it’s my culture. I do hip-hop because I love hip-hop.”

Hip-hop artists like Propaganda and Sho Baraka may not be trying to communicate good theology. They may not be striving to arrive at Hauerwas’s definition of good theological writing. They do not ask listeners to agree with them. But they do force us to think. They set a massive scratch into our untested assumptions. Hip-hop flips the script, forcing us to ponder anew any trite assertions that have become too familiar. And that’s what makes it good.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Flipping the script.”