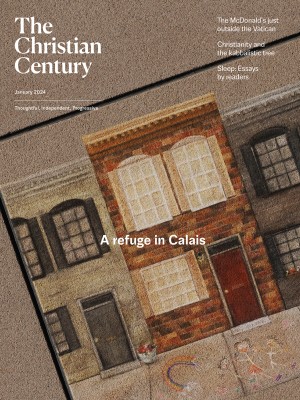

In 2016, a McDonald’s franchise opened in the Borgo Pio neighborhood of Rome, just outside Vatican City. St. Peter’s Square is seen in the background. (Tiziana Fabi / AFP via Getty Images)

Early in the morning, when Pope Francis has just finished preparing his homily for the daily mass and the great doors of St. Peter’s Basilica are poised to groan and be hauled open, the first congregants gather in the McDonald’s just outside Vatican City.

At this time of morning the booths with outlets—prime real estate—fill quickly with middle-aged men wearing multiple coats. Before some of them must hurry out into the crowds and try to sell rosaries, umbrellas, power banks, tours, before others must go to hawk and fidget from behind tiny cart stands, before the remaining few sit on plastic crates and beg, they breathe in this time to sit and stretch their legs.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

The Discalced Carmelites who come to Rome are not, despite their name, usually barefoot, but other zealous pilgrims and wanderers sometimes are, including one regular customer. He is asking for change this winter morning, from anyone who looks as though they might have change to offer. His tunic and coat drag on the ground, and so it is a grace that they were dark brown to begin with. He would like a caffè, and he makes his rounds among the plastic-cushioned booths.

On-duty Italian soldiers and off-duty Swiss Guards file in from time to time: this is the closest free bathroom to their post, and they are not going to pay to urinate in the city they are protecting. Like them, most people here this early in the morning are not buying food. There are few fries to fry. Nevertheless the empty fryer beeps periodically like the bells of some interplanetary chapel, keeping the time.

The McDonald’s in the Borgo Pio neighborhood might be the closest thing St. Peter’s has to an antechapel, used for pre-church warmth and arrangement and for post-church hanging about. Actual antechapels are rare in Italian churches, and there is no obvious place inside St. Peter’s to prepare for, or rest after, whatever overwhelming encounter with the Divine happens there, so the comers and goers have naturally chosen the Golden Arches one block northeast to fill this role.

When the fryer beeps 11, a papal mass is underway in the basilica, and the McDonald’s half fills with those who did not get a seat in Francis’s presence. It is not a bad second choice, for though there is no supreme pontiff and no great cavernous hall, there is still a crowd, and therefore every tragedy and aspiration, every manner and principle of humanity that the pope could possibly address—and in addition, McToasts and Sweet Temptations. The displaced hopefuls leaving Vatican City are joined in the McDonald’s by other, fresher hopefuls stopping here before the basilica opens to the public again at noon.

When the mass ends and the flood of people is released from the bronze doors, the McDonald’s fills at a rapid pace, and those who are sitting alone begin to yield their seats to families and migrate to smaller spaces and the tall stools in the corner. When the Model EU team from Florence leaves its tables, it is immediately replaced by a mass of pilgrims speaking Tagalog, which in turn is replaced by a wedding party, all but the bride. Now people sit with strangers; now they eat standing in front of the counter. It is seven to a booth, now eight. The double-coated men have long since gone.

This is an antechapel only with respect to its function, as a holding place relative to the mass. Having little physical or metaphysical in common with its referent, in all other respects it is more like an anti-chapel, a cosmic opposite of the basilica with which it shares most of its visitors. This McDonald’s, however adapted to its prestigious surroundings, is still a McDonald’s: young, fluorescent, low-ceilinged, glaring all over with advertisements for itself on ever-changing screens attached to tables, walls, and floors. All of the surfaces have a slight oily sheen that almost certainly has nothing to do with anointing. At any given time one of the ice cream machines is broken, and someone is unhappy about this. The noise of the place, by noon, could invade the innermost mind of the most serene Trappist.

But this establishment does have its own kind of decorum. On the south wall, a facade of ancient sandstone dotted with vines and pigeonholes has been screen-printed from floor to ceiling. Faux wood accents adorn the doorways and the trash can; there is a new and rather appealing McCafé pastry display. Nor is it without its celebrated figures: for 25 years Pope Benedict XVI, when he was the cardinal responsible for overseeing church orthodoxy, lived upstairs. His cardinal successor inhabits the apartment now, promoting and defending the doctrines of the Catholic faith while resisting the tempting smell of McNuggets wafting up from below. And the place does, to its credit, have more beautiful plastic chairs than the basilica does. But noise, crowding, and impatience are constant forces here, and the primary aromas are of grease and difficulty.

The basilica next door is all transcendence: the height of the dome, the richly patterned spotlessness, the angelic visitations, the swirling layers of time and mystery and incense, a place that would take a hundred people a thousand years to understand. This unaccountable place sings of the strangeness of the world: that otherworldly things are among us, that the receipts and protocols and kinds of hunger that saturate us all day long are not the founding principles of reality, that there really must be some kind of magic around that we have been ignoring but no longer can.

Before and between these encounters we need a place to sit, to take the pressure off of our backs and feet, to eat our requisite calories, or we might never see the glory of the glorious thing in the first place. So the basilica and the fast-food place, like the spirit and the body, thwart each other and make each other possible. In St. Peter’s the people hear, though the nearest neighbors may be wrapped in their coats wading separately through the infinite floor, of the high call to love their neighbor as themselves. In the McDonald’s they are close enough to their neighbor to know what he smells like.

There are other restaurants in the Borgo, of course, finer establishments that have subtler lighting, less crowding, and nothing of the sense of refuge and relief. Someone is watching all the time, and asking questions, and you are only allowed to sit there if you pay, and only for so long. The men who work at the tiny alleyway convenience stores packed from floor to ceiling with bruised fruit, the cashiers at the religious regalia shops full of bright bishops’ cassocks and golden monstrances and life-size sculptures of Mary, the fellows hawking skip-the-line tours of the Sistine Chapel—all these, if they have not made some special agreement with a pizza seller, are likely to prefer the McDonald’s. Even the pizza sellers sometimes sit in the McDonald’s on their breaks.

In 2016, when it became known that this franchise would be coming to the shadow of St. Peter’s, there were all the expected reactions: outrage, petitions, committees. Understandably, the proprietors of the smallest and cheapest of the pasta shops were concerned for their livelihoods. And understandably, residents cringed at the thought of the American behemoth edging in between the Renaissance architecture and the ancient cobbled streets. The cardinals who lived upstairs wrote angrily to Pope Francis, and a Committee for the Protection of the Borgo lamented this tragic fall of a neighborhood already suffering from such blights as mini-marts and souvenir sales.

Cardinal Elio Sgreccia, president emeritus of the Pontifical Academy for Life, who did not live above the site, took particular grievance with it. “I repeat, the mega sandwich shop in Borgo Pio is a disgrace,” he told reporters at the end of an interview in La Repubblica. “It would rather be appropriate to use those spaces for activities in defense of the needy in the area, spaces of hospitality, shelter, and help for those who suffer, as the Holy Father teaches.”

He spent most of the interview, however, discussing aesthetic concerns: such an “aberrant” choice breaks with culinary tradition, is “not in line with the aesthetics of the place” and serves “foods [he] would never eat.” If the cardinal had been asked to choose between a refined Italian restaurant which fed refined food to refined tastes and an eyesore which gave shelter to the poor, he might have been hard-pressed to answer.

The McDonald’s may in fact be one of the most helpful places for giving “hospitality, shelter, and help” to the worn-out traveler or the itinerant person, especially those who would rather not feel so keenly as though they are being helped.

First, and most evidently: it has cheap food. Miraculously, there are still a few things you can get for a euro. Second: the place is well insulated and temperature controlled, which means reliable relief from the summer heat and the winter cold. Third: restrooms, unlocked. This provides both the obvious kind of relief and the benefit of free water from the sink, though warm and iron tasting. Fourth: there’s Wi-Fi, not fast but free, and outlets. Fifth: no one is looking at you, not really. This differentiates it from the kind of explicitly charitable place that may provide great care but which has very little in the way of anonymity. There is no screening process, no stern interview at the door. McDonald’s is trying to get people in, not out. Sixth: it is open every day, without fail, from 7 a.m. to at least midnight, covering the whole period of the day when the shelters and hostels are closed and then some.

Last, and most importantly: you can sit inside without having bought anything. Say what you will about McDonald’s—its origins, its corporate structure, its garish American ubiquity, its food. But those locations that, under merciful management, allow people to sit without a receipt are all over the world places of special shelter and refuge and in this way do a great service to humankind. Besides all this, to answer the late cardinal, the restaurant pays the Holy See 30,000 euros each month, a sum that could fund several shelters, to provide these basic needs to the poor and pilgrim.

This McDonald’s continues in the tradition of medieval rest houses, where a millennium ago pilgrims could stop, between seeing holy sites and adding to their collections of shiny pilgrimage pins, to eat and rest. Pope Leo III built a rest house near here around the year 800, a house “of wonderful size,” according to the Liber Pontificalis, complete with fine decorations, dining couches, and a bath. A poor pilgrim could find a fast meal at a diaconia, a type of serving house adapted from the ancient food distribution services of Egyptian monasteries. All had the same general name and mission, and all were appointed by the pope, but each was separately managed and owned its own property, more independent and haphazard than a franchise system but to similar effect. Five of them were established in the Borgo, primarily working to provide pilgrims and the poor in the vicinity of the basilica with food and occasionally a bed. A supplicant to St. Peter or a homeless Roman might more reliably find shelter at one of at least three xenodochia in the neighborhood, places for receiving strangers. They were places of unusual amalgamations of people: St. Cummian wrote that some visiting Irish priests were surprised to find themselves packed into a xenodochium with “a Greek, an Egyptian, a Hebrew and a Scythian.”

The lines blurred between the food and shelter services because everyone always needs both. The lines blurred, too, between the kinds of people who came. The Liber Pontificalis often refers to them together: “poor and pilgrims” or “Christ’s poor,” a phrase that indicates both groups. The local poor and the weary visitors from far-flung places were considered in the same category. Today’s traveler-pilgrims might think themselves quite different from the local people experiencing poverty, but looking at their most pressing motivations, the old comparisons still hold.

At the peak of the post-mass rush at the McDonald’s of Borgo Pio, whole families are sitting outside on the low window ledges. In terms of dirt and cigarette ash and the possibility of insects, it is equivalent to sitting on the sidewalk, but people are keen to differentiate themselves from other sidewalk sitters. When the ledges are full, the multitudes of McDiners spill out into the Piazza della Città Leonina, carrying their spotted paper bags. They gravitate toward the low wall that runs through the center of the plaza, because it feels more dignified than sitting on the ground, even though seagulls perch on this wall specifically to relieve themselves.

Back inside, three young women in office wear leave their trays of McChicken wrappers behind. A barefoot man appears out of his slow wandering and sits to investigate, crinkling through the white-and-yellow papers with his hands in search of a crescent of leftover sandwich. They come up empty. He could use something to eat. But for now he leans back and allows the finished tray to justify his sitting there, to signal that he’s a paying customer—as if the workers have not, despite their own exhaustion, noticed him. They do not tell him to leave. Other diners—the ones who forget they are in an antechapel and a rest house—sometimes do tell him to leave, grimacing at his difficult aroma. But moments ago, sitting on the wall among the droppings, their own hope was the same: to get a place at the table, inside, where warmth and cushions are, because they have all been walking from place to place and carrying their things with them all day, wondering at the world but really looking for relief.