Following the suffering Christ

Discipleship-as-self-improvement doesn’t much resemble the way of Jesus.

Dorothy Day gave up smoking for Lent every year. Apparently, this made her so irritable that friends prayed she would take it up again, which she did. Thus the determination to quit the next year, and the next.

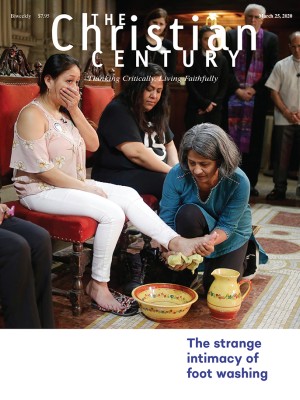

Lent can be relentless. There’s so much of the body in it. This isn’t surprising, since Lent prefigures the Passion: a human body’s experience—at the hands of imperial power—of abuse and torture, suffering and death. Lent is also preparation for Easter, when Christians make the absurd claim that Jesus’ body has been raised—and that through ritual actions involving water, wine, and bread, another body is constituted to do his bidding in a world of abuse and torture, suffering and death.

I have often found myself wanting to fix something about my own body during Lent: giving up guilty pleasures of one kind or another, or doing good deeds that might make me feel better about myself. But discipleship-as-self-improvement doesn’t much resemble the way of the crucified Jesus. For those whose bodies are privileged, varyingly so in a culture like ours, what does keeping a holy Lent look like?

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Mary Karr’s poem “Descending Theology: The Crucifixion” paints a picture of tragicomic vulnerability: “You’re not the figurehead on a ship. You’re not / flying anywhere, and no one’s coming to hug you. / You hang like that, a sack of flesh with the hard / trinity of nails holding you into place.” The image of Jesus’ body as an abandoned “sack of flesh” won’t let us get away with sanitizing or spiritualizing the brutality. Earlier in the poem comes the observation that to be crucified is “to have oafs stretch you out / on a crossbar as if for flight.” The humiliation and degradation of body and spirit, the pathos of false expectation (as if someone is “coming to hug you”), and the utter powerlessness of this body should prevent us from fetishizing the cross and sentimentalizing its victim.

For those of us whose bodies are privileged, can Lent open our eyes and hearts—meaningfully, materially—to neighbors whose bodies are routinely under scrutiny, under suspicion, under surveillance, who experience humiliation and degradation in the streets and in the courts, who are powerless against unjust systems and laws? Can we recognize the likeness of the crucified Christ in abused black and brown bodies in for-profit prisons, in the tortured bodies of sexual minorities, in the suffering bodies of babies separated from their mothers at the border?

I am reminded of the life and witness of Franz Jägerstätter, recently brought to the world’s attention through Terrence Malick’s exquisite film A Hidden Life (as much as an art film by the erudite recluse Malick can command the world’s attention). A Catholic and an Austrian army conscript, Jägerstätter refused to swear an oath of loyalty to Hitler. Harassed by both civil and ecclesiastical authorities, he held fast. An unwillingness to swear allegiance and to fight in “the good war” was treachery in his social orbit and treason according to the law. Although he agonized over what his death would do to his wife and three young daughters, avoiding his fate was not an option. A year younger than Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Jägerstätter was beheaded in 1943 and beatified in 2007, setting a precedent for conscientious objectors to be counted as martyrs by the church.

But he’s practically a saint, we might say. To which we might imagine Jägerstätter responding with one of Dorothy Day’s famous lines: “Don’t call me a saint; I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” We don’t remember Day for quitting cigarettes during Lent; we are moved by her life’s work and chastened, perhaps, by her conviction that America’s war economy and the engine that drives it—predatory capitalism—rob the poor of their dignity and deceive the privileged about their power. The corporal works of mercy at the heart of the Catholic Worker movement Day helped to establish are intimate, human gestures of gospel caritas. As she often asked: What else do we all want, each one of us, except to love and be loved?

When challenged by his bishop to consider his obligations as a husband and father, Jägerstätter responded by asking if these obligations required him to kill other husbands and fathers. His extraordinary witness is rooted in the questions that all ordinary followers of Jesus must ask themselves: Which stories do I live by? What does love of neighbor require of me? Where does my ultimate allegiance lie? When I consider the witness of Day and of Jagerstätter, I let myself off the hook if I think I am called to a discipleship less costly than theirs.

All of this matters all of the time, not only during Lent, since the way of the cross is the Christian life in sum. Yet boutique discipleship is always seductive—tidy, programmatic efforts at personal growth that can keep me at a safe distance from my neighbors in need. In these dark times, evils we might have thought long banished or repudiated are visited on the bodies of the most vulnerable among us (and on the planet that hosts us all), giving credence to Czesław Miłosz’s observation in 1930s Poland that “if a thing exists in one place, it will exist everywhere.” A holy Lent and our faltering attempts to live holy lives mean going where the suffering Christ is and, like Day, Jägerstätter, and so many others, bearing witness.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Following the suffering Christ.”