Who are our neighbors?

A startlingly large number of Americans support immigration arrests in houses of worship.

Source image: Thomas Berberich / iStock / Getty

Just two days into his second term, President Donald Trump, self-declared defender of the cross of Christ, took action to make churches less safe: he reversed a long-standing federal policy preventing immigration agents from arresting people inside houses of worship.

A new survey confirms that Trump did this with solid support from his political base. According to the Pew Research Center, 52 percent of Republicans say they are in favor of immigration arrests inside houses of worship. Only 15 percent of Democrats say they support this policy. A similar number of Republicans (50 percent, compared to 9 percent of Democrats) also say that deporting people living in the US illegally would make life better for “people like them.”

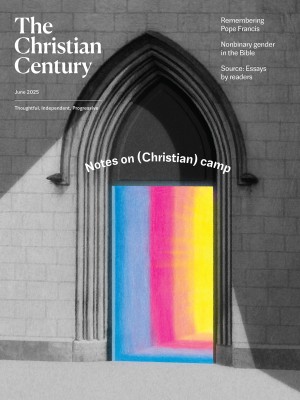

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

People like them. This small phrase is perhaps the weightiest part of the survey data. Is our moral responsibility only for those we consider to be like us? What if we had the chance to ask Jesus, “Who is our neighbor?” What would we want his answer to be?

The Pew survey also asked if respondents are worried that they or someone close to them might be deported. Only 10 percent of Republican or Republican-leaning adults answered yes. It appears that many of the most enthusiastic supporters of Trump’s dangerous immigration policies don’t think they even know anyone who is likely to be affected by them.

“Neighborliness is nonspatial,” writes Howard Thurman in his seminal book Jesus and the Disinherited. “It is qualitative.” Our neighbor, that is, can be anyone. For Thurman, neighborliness has nothing to do with who’s in our demographic or even in our physical proximity. It has everything to do with justice and, for those professing to follow Jesus, an all-encompassing, Christlike love.

Churches in the United States have a long history, if far from a perfect one, of extending this kind of neighborliness. Two hundred years ago, churches often served as stops on the Underground Railroad. In the 1980s, hundreds of churches opened their doors to refugees fleeing political violence in Central America—violence that was in large part the result of the United States itself acting as a bad neighbor.

And today it is faith groups—led by a coalition of Quaker meetings—that are suing the Trump administration to prevent immigration raids in houses of worship. “The Quakers are so angry,” said TikTok influencer Glo, herself a Quaker, in a January post. “Quakers will not stand to have [a] meeting for worship disturbed and perturbed by ICE agents. . . . They will not tolerate that happening to anybody.”

Thurman writes that we are to love our neighbors “directly and clearly, permitting no barriers in between.” Pentecost is a great time to remember that the barriers we’ve constructed between ourselves and others are artificial. When the Holy Spirit alights, everyone receives an invitation to the table.

There is no “them” in opposition to “people like us.” We are all neighbors, and we cannot tolerate government agents coming into our churches and harming our neighbors.