The way out of partisan gerrymandering

Beyond the current Supreme Court case, there are deeper problems—and possible solutions.

It’s a persistent problem in U.S. politics: many voters don’t have a meaningful impact on elections. This leads to disengaged voters and unaccountable elected officials, mutually reinforcing ills that erode democracy.

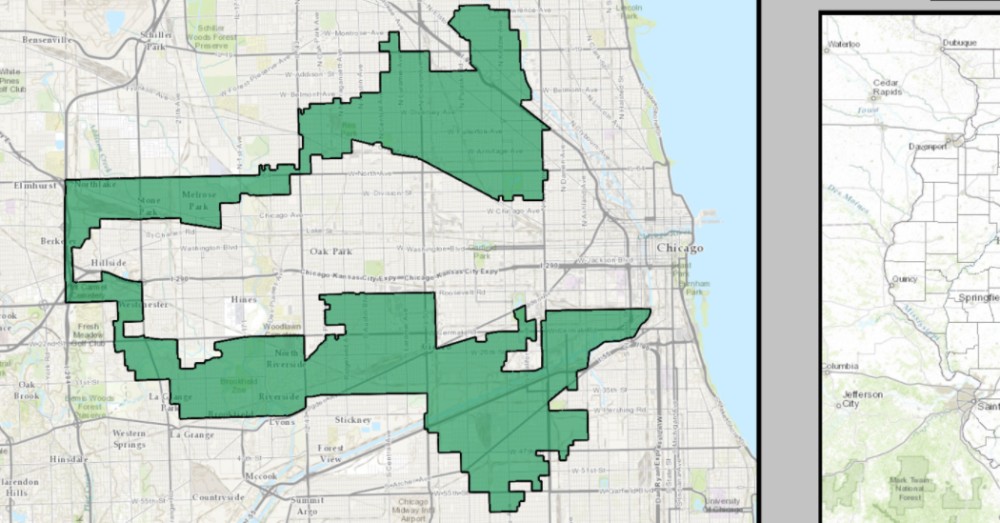

The rise of partisan gerrymandering has exacerbated the problem. The practice isn’t new; any time politicians have been in charge of drawing legislative districts, they’ve tended to draw them in service to their own interests. But after the 2010 census, state legislatures—most of them run by Republicans—got really, really good at this. The result is a U.S. House of Representatives dominated by safe seats that incumbents barely need to bother defending.

So far the Supreme Court has declined to intervene. But a 2004 opinion by Justice Anthony Kennedy hinted that the court might step in if a case articulated a specific way to measure the problem. Now the court has agreed to hear a case that does just that.

Gill v. Whitford was originally filed by a group from Wisconsin that argued that the state’s 2011 redistricting resulted in a large “efficiency gap” between the parties: far more Democratic votes are wasted than Republican ones. Wasted votes, by the plaintiffs’ definition, come in two forms: votes for a losing candidate and surplus votes that pad the winner’s margin. Since gerrymandering works by setting up wins in relatively close races while conceding landslides elsewhere, an effectively gerrymandered state will have a significant efficiency gap.

If the court chooses to draw a line and call foul on Wisconsin, it will be a big win for democracy—a corrective to a flagrant instance of public servants acting purely as partisans. It will not, however, address the strong incentives they have to act this way in the first place. The court can limit the harm, but the only way to depoliticize redistricting is to take politicians out of it.

Four western states offer a better model: an independent commission, not the state legislature, draws the districts. This approach deals with the root of partisan gerrymandering—partisanship itself. Yet even here, wasted votes and efficiency gaps persist. That’s because gerrymandering merely exploits and intensifies deeper issues: in an era of deep partisan loyalty, voters tend to live in like-minded clusters. And our winner-takes-all electoral system drastically limits the power of their votes.

The organization FairVote proposes an ambitious, two-pronged electoral reform to address the problem. Instant runoff voting would invite voters to rank candidates instead of just choosing one—making space for bridge builders and third parties, discouraging negative campaigning, and empowering citizens to do more than just stand with or against the majority. Multiseat districting would put voters in larger districts and give them more than one representative—ensuring that virtually all voters have at least one member they actually voted for.

The point of such proposals is to make every vote count—not just literally counted, but with a meaningful effect. Cracking down on partisan gerrymandering is a crucial part of the effort, but it’s only a start.