Which new books deserve a spot under the Christmas tree?

We asked our contributing editors to each pick two.

Adam Hearlson: David Grann is probably the country’s best narrative nonfiction writer. Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI (Vintage) is an impeccable account of the vast conspiracy that preyed upon the Osage Indian tribe in the 1920s. The research is thorough, the writing is crisp, and the story is heartbreaking. What sets this book apart is Grann’s ability to trace the ways in which the trauma of the past remains deeply embedded in American life.

I like giving cookbooks as gifts. Some books are full of killer recipes (Ad Hoc at Home, by Thomas Keller), some are fascinating reads (The Momofuku Cookbook, by David Chang and Peter Meehan), and some are indispensable classics (Essentials of Italian Cooking, by Marcella Hazan), but few cookbooks teach you how to cook. Samin Nosrat’s Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking (Simon & Schuster) will improve the cooking of novice and expert alike. It is filled with practical wisdom and beautiful illustrations. Its central advice about the complex interplay between four ingredients—salt, fat, acid, and heat—will be in the back of your head the next time you dig into your refrigerator hungry but with no dinner plan.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Stephanie Paulsell: In Joy Williams’s Ninety-Nine Stories of God (Tin House Books), some of the microfictions feature God as a character, and others don’t—but all of them keep us on the lookout. In some stories, the Lord is plain to see: God adopts a tortoise, plans a dinner party, visits a psychic in Maine. In other stories—about a nameless dog who saves a baby, for example, or the whirlwind of trouble with which a woman copes alone—the idea of God hovers. In still others, God is expected but never shows up. Williams’s witty, quietly startling stories repay repeated readings. As the narrator of one story says: as impossible as it is to think about God rationally, that doesn’t mean we should give up.

Tracy K. Smith’s immaculate poems in Wade in the Water (Graywolf) cultivate encounters with angels, with God, and with history. Some are “erasure poems,” which delete words from documents (like the Declaration of Independence and the correspondence of slaveholders) until an erased history shines out clearly. Some, like “Refuge,” pray that our moral imagination may grow until we are “willing to cede” what we have so that others may have what they deserve. Every poem in this collection makes a claim on us.

Bill McKibben: Jill Lepore’s These Truths: A History of the United States (Norton) is a remarkable account of American history, and one that starts to answer what seems to me a crucial question: What if anything in our heritage as a nation is still usable in the fight for a better future? Once we face squarely the stains of slavery and of the genocide against the continent’s original inhabitants, are there still stories we can tell to inspire and inform us as we try to build a better nation? In this political moment, there can be few more useful books.

We may also be in need of A Natural History of Beer, by Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall (Yale University Press). Few things date further back in history than beer, and few have changed as much in recent years—and for the better. It was with beer that the turn to the local began in the 1970s. Even as one worries that the world is going straight to heck, this book is a reminder that we definitely have better things to drink than we used to. The book won’t be released until February, but for Christmas you can give a six-pack of your favorite local brew along with the promise that the book is on its way.

Thomas Long: Maryland’s Tangier Island has been a fishing community for 240 years, but the small island is sinking into the Chesapeake Bay at an alarming rate. The fewer than 500 residents remaining are huddled onto small ridges barely above sea level. Scientists predict that by about 2050 the island will be gone. In Chesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier Island (HarperCollins), Earl Swift, who lived for a year on Tangier, has crafted a loving, sometimes witty, and always fascinating account of how this sternly Protestant community moves to the rhythms of the tides and the blue crabs, stubbornly denies climate change even as the waters rise, and bravely faces the coming apocalypse.

In a time when our treasured ideals and revered public institutions are under assault, it is both a comfort and a recalibration to encounter Jill Lepore’s highly readable These Truths: A History of the United States (Norton). Lepore, a Harvard historian, traces the American story from Columbus to the election of Trump, with an emphasis on democratic institutions and the realms of law, religion, journalism, and technology, “because these are places where what is true, and what’s not, have sometimes gotten sorted out.” What better gift than an attractively written book that offers some learned and intelligent wisdom for doing the sorting?

Debra Bendis: I’ll give Days without End (Penguin) to my daughter-in-law, as we share a passion for brilliantly written novels. Sebastian Barry’s book includes numbing, brutal accounts of war, but the language is so beautiful and honest and heart-rending that I wanted to be part of it. Fifteen-year-old Thomas flees the Irish famine and meets John Cole in St. Louis. “I was sick of hungering,” says Thomas of their decision to become soldiers in 1851. The two boys “didn’t hardly know nothing” when they are directed to kill Indians and later Confederate soldiers. Fifty years later Thomas tells his story, trying to make sense of his survival in a violent society and time, and sharing the humor, love, and human tenderness that helped him survive and create a life without war.

My gardener friend who is endlessly curious about plants and their potential for human healing will receive a copy of American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic (Liveright). Victoria Johnson tells the inspiring story of David Hosack, the doctor who assisted at the Hamilton-Burr duel. The impassioned surgeon, botanist, and public figure collected plants from around the world, set up a botanical garden (on the land where the Rockefeller Center now stands), and did his own pharmaceutical research. He advocated for government investment in gardens and plants as an investment in public health. His unusual zeal for directing his boundless curiosity, intellect, and energy to public health seems needed in 2018.

Will Willimon: Austin Channing Brown was named Austin because her parents hoped that in a world of white supremacy, future employers would think she was a white man. I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness (Convergent) is a gripping story of a courageous woman who wrenches dignity in spite of everything. Part of the power of the book is that Brown’s testimony, though moving, is not unusual. This is necessary reading for people of my race who think that race doesn’t matter.

Gerry Bowler is the dad of my friend Kate Bowler, whose recent Everything Happens for a Reason has been widely read. Now that Trump has commenced hostilities with Canada, what better time to read a book by a Canadian who is the world’s foremost authority on the circuitous history of Christmas. With wit and lively insights, Gerry helps us understand the alleged “war on Christmas” in Christmas in the Crosshairs: Two Thousand Years of Denouncing and Defending the World’s Most Celebrated Holiday (Oxford University Press). Perfect for Christmas giving!

Robin Lovin: Books about ethics tend to be didactic. History, art, and literature make better gifts. For our situation today, I recommend Joel Richard Paul’s Without Precedent: Chief Justice John Marshall and His Times (Riverhead). Paul shows us Marshall’s truly original effort to create an independent judiciary, but he also lets us see ordinary politics in the late 18th century and even the details of Marshall’s legal practice. Marshall was that rare combination among American revolutionaries, a Virginian who was also a Federalist, and he was America’s representative in Paris during the Reign of Terror. Thus, he saw matters a little differently from his neighbor, Thomas Jefferson.

Yang Liu also provides a different perspective. She’s a Chinese artist living in Berlin, and East Meets West (Taschen) presents her two worlds in contrasting pictograms. On the left (blue) page, a pair of footprints treads directly across a dark circle. On the right (red) page, similar footprints step warily around it. Small captions in English and Chinese identify these as ways of “Dealing with Problems,” East and West. The 50 provocative and insightful contrasts sometimes make you think a minute to figure out what’s being depicted, but anyone who has tried to live in two cultures will get the message.

Kathleen Norris: I’d get the adults on my list Exit West (Riverhead), a novel by Mohsin Hamid. A modern fairy tale and a love story, Exit West begins in an unnamed country in a time of war and takes us through magical doors into the world of today’s refugees. The reader is left to wonder: Who do we care about? Who do we care for?

With four young grand-nieces, I’m also into picture books. The delights of Patrick McDonnell’s The Little Red Cat Who Ran Away and Learned His ABCs the Hard Way will endure over many rereadings. A less playful but lovely book is Jo Ellen Bogart’s The White Cat and the Monk: A Retelling of the Poem “Pangur Bán” (Groundwood). “Pangur Bán” is a poem about a cat that was written by a ninth-century Irish monk and placed in the margins of an illuminated manuscript. The monk reflects that, as the cat hunts mice, he hunts for meaning in the scriptures. In Bogart’s retelling, suspense builds in subtle, gray scenes of the cat prowling the monastery. Then we’re treated to a colorful manuscript page with a cat chasing mice, a rabbit blowing a trumpet, and a monk riding on a letter shaped like a dragon. Children will be delighted by Sydney Smith’s illustrations, and adults can ponder the ways images transport us back to our preliterate minds, awakening our appreciation not only for words but for the world around us. Which includes little white cats.

Martin B. Copenhaver: There Is No Good Card for This: What to Say and Do When Life Is Scary, Awful, and Unfair to People You Love (HarperOne) is the product of an unlikely pairing of co-authors: Kelsey Crowe, who has a doctorate in social welfare, and Emily McDowell, a maker of greeting cards. The graphics in the book even resemble what one might see in a greeting card. But don’t let appearances fool you. This book contains some of the soundest and most practical advice I have ever encountered for those who want to be helpful to loved ones going through a hard time.

Clarence Jordan, 50 years after his death, finally has a biography worthy of him: Clarence Jordan: A Radical Pilgrimage in Scorn of the Consequences, by Frederick Downing (Mercer University Press). Jordan will be remembered for many things: for writing the Cotton Patch paraphrases of the New Testament, cofounding Koinonia Farm, a multiracial intentional Christian community in rural Georgia, and helping Millard Fuller found Habitat for Humanity. Jordan’s approach to the gospel seems as radical today as it did when he was alive. And it’s just as needed. Reading about Jordan’s life is nourishment and encouragement for those who, in their own ways, are taking up the cause of holy resistance.

Beverly Roberts Gaventa: Jenny Erpenbeck’s novel Go, Went, Gone (New Directions) opens with Richard, a recently retired classics professor in Berlin whose horizon extends no further than lunch, yard work, and the reorganizing of his library. Learning from the evening news of young African refugees camping in the Oranienplatz and realizing he has passed by them without even noticing, Richard sets out to learn. His vague curiosity propels him to meet them. What emerges is an understated yet compelling portrait of unlikely friendship. I might give this book to that uncle who just does not understand why “those people” behave as they do, but I am more likely to give it away just to generate a conversation partner.

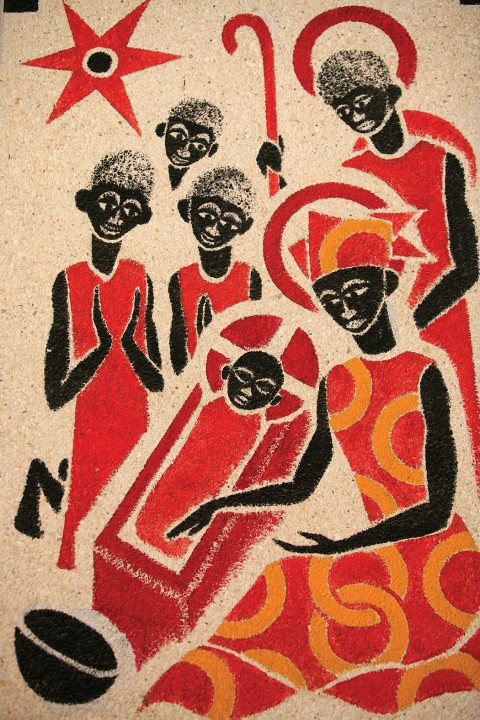

The title tells the tale of What Do You Do with a Voice Like That? The Story of Extraordinary Congresswoman Barbara Jordan (Beach Lane Books). Chris Barton has produced a children’s book about Jordan that takes up her distinctive voice and her wise use of it in public life. Beautifully illustrated by Ekua Holmes, the book instructs its readers about an extraordinary woman, but it also invites them to find their own voices and put them to use to make the world a better place. I need to give myself a copy, since my grandson is tired of loaning me his.

John M. Buchanan: Novelist and essayist Marilynne Robinson is at her best in What Are We Doing Here? Essays (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Her subjects range from Ralph Waldo Emerson to Jonathan Edwards to John Calvin to the virtues of living in the Midwest. These essays could not be timelier. In the preface, she writes: “We have surrendered thought to ideology,” a statement corroborated by each presidential rally and tweet. A sentence in the first essay perfectly catches the present moment: “A society is moving toward dangerous ground when loyalty to truth is seen as disloyalty to some higher interest.” Nevertheless, Robinson remains hopeful. These essays warrant careful, slow reading, one at a time.

Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries from a Secret World (Greystone) is a revelation and a delight. A German environmentalist, Wohlleben has been watching and studying trees for a long time. His conclusion, backed by fascinating data, is that trees are social beings. They live like families, care for and support children, and warn other trees of impending danger. A walk in a forest is refreshing because trees function as giant air filters, producing cleaner air under their branches. Mature beech trees blossom every three to five years, drop 30,000 beechnuts, and send more than 30 gallons of water coursing through their branches and leaves every day. This book is so good, I’m reading it a second time.

Ralph C. Wood: Eugene Vodolazkin is a 54-year-old Russian medievalist and a remarkable novelist. He is also an Orthodox believer whose faith suffuses his fiction in surprising ways. Laurus (Oneworld) is set in the chaos of medieval Russia. Arseny, the protagonist, experiences the world both vertically and horizontally at once. He inhabits seemingly disjointed but intricately related versions of his singular self—healer, holy fool, pilgrim, monk. Hence Vodolazkin’s implied question: What kind of faith would be required to live such a porous life, wherein the temporal constantly intersects the eternal, within our late secular age?

In The Aviator (Oneworld), the diarist narrator has been born in 1900 but, preserved by Soviet cryonics, awakens in 1999. Innokenty’s memories of Russia’s horrors—especially the revolution and the Gulag—gradually emerge. He thus struggles to take up his new life amid the trivialized time of the late 20th century. His question is also ours: How shall we live amid our latter-day ruins? For Vodolazkin, truth is found not in the grand movements of history so much as in the small things that remain truly universal—a grandmother’s cough, the scent of something fried, the smoke of a father’s cigarette. Such is Vodolazkin’s modest, difficult, but trans-temporal hope in a time-bound age. Both novels would make splendid Christmas gifts to friends or family members who want to be radically challenged in their reading.

Kathryn Reklis: For every nerdy TV lover in my life, I am recommending my friend Martin Shuster’s new book New Television: The Aesthetics and Politics of a Genre (University of Chicago Press). Shuster gives a robust philosophical vocabulary to explain what is so compelling about the best TV out there (and what makes it “best”). He puts the genre into a long history of how we talk about the relationship between art, politics, and other ways we make sense of our lives together. Just like I do when I am watching good TV, I find myself absorbed, arguing back, or wanting to start a conversation with friends about his ideas.

I rapturously devoured Lily King’s novel Euphoria (Grove) over the summer. It reimagines the life of early anthropologist Margaret Mead as she does fieldwork in the years leading up to World War II. As she, her fellow anthropologist husband, and their colleague try to puzzle out the unfamiliar cultures around them, they are thrown back into the far stranger territory of their own inner lives. There is love, sex, death, and mystery, but the book also captures the impossible euphoria of shared thinking and the power of ideas to change the world beyond the thinker’s control.

Dean Peerman: Kate Harris acquired wanderlust at an early age. In Lands of Lost Borders: A Journey on the Silk Road (Dey Street Books), she recounts retracing Marco Polo’s path on the ancient network of trade routes between Asia and Europe that are collectively called the Silk Road. Harris and a friend undertake a strenuous ten-month trek from Turkey to India, mostly by bicycle. At night they usually pitch their fold-up tent, but on occasion friendly strangers give them lodging. One kind woman even insists on washing their hair (which by that point is sorely needed). The real value of modern exploration, Harris maintains, “lies in how it expands our consciousness, our sense of connection with each other and the universe of which we are a part.”

In Couchsurfing in Iran: Revealing a Hidden World (Greystone), German journalist Stephan Orth tells of his travels through “the only Shiite nation in the world.” Traveling by bus and thumb (he hitchhiked a lot), Orth found hosts through the couchsurfing website, which brings together “intrepid wanderers and willing hosts.” Iran has thousands of such hosts despite couchsurfing being illegal. (Discretion is the watchword here.) Orth stayed with a variety of people, a few of whom were engaged in a second illegal activity, such as selling wine on the black market. Countless Iranians could be said to be leading a double life, ironically experiencing freer lives behind walls. Orth says he frequently was “enchanted and outraged at the same time.”

Richard A. Kauffman: Since 9/11, popular interest in Dietrich Bonhoeffer has spiked. From John Shelby Spong on the left to Richard Land on the right, many have held up Bonhoeffer as a model, especially for resisting what is perceived as an autocratic federal government. In The Battle for Bonhoeffer: Debating Discipleship in the Age of Trump (Eerdmans), Stephen R. Haynes gives a readable account of this resurgence of interest in Bonhoeffer. Haynes scrutinizes Eric Metaxas, whose biography was a New York Times best seller—not least for using Bonhoeffer in the defense of conservative politics in the United States, but also for playing fast and loose with what is actually known about Bonhoeffer. Haynes, who once considered himself an evangelical, ends with a poignant “open letter to Christians who love Bonhoeffer but (still) support Trump.”

In Why? Explaining the Holocaust (Norton), Peter Hayes, longtime scholar and professor of holocaust studies, asks (and answers) one of the most enigmatic questions of modern times: Why did the Holocaust happen? Subsidiary questions are: How could this have happened in Germany with support of so many of the elite and even many Christians? Why did the Jews face the vitriol of Hitler’s and his supporters’ anger? Why was there so little protest, both inside and outside Germany, against these ghastly deeds? Hayes concludes by pondering the legacies of the Holocaust and what we can learn from this dark time in our relatively recent past. The question remains: Can it or something like it ever happen again?

Lillian Daniel: In Andrew Sean Greer’s Less: A Novel (Back Bay Books), the hero, Arthur Less, is a middle-aged writer whose peak creative years and romance years seem to be behind him. Once the beautiful younger lover of a more famous writer, Less is now the older writer, minus the fame, with a younger lover who has recently dumped him and is now engaged to a more dependable man. Determined not to mope as his ex’s wedding day and his 50th birthday approach, Less impulsively accepts every weird writers’ conference invitation that has come his way. From Germany to India to Mexico to Morocco, we tag along—laughing in recognition as Less flees from himself, cheering and wincing as he stumbles into whatever is next.

Laughing at the Devil, by Amy Laura Hall (Duke University Press) is a fresh take on Julian of Norwich that you don’t need a divinity degree to understand. In an age of plague and peasants, when women were seldom heard, let alone read, Julian is believed to have produced the first book written in English by a woman. Since she was named after the church she lived in, we don’t even know her real name. But in Hall’s hands, Julian the anchorite mystic becomes a spiritual friend. She may have prayed in mean and miserable times, but she gets a generous vision of God’s love for us all.

Jason Byassee: The books I’m most eager to give to friends this Christmas display a bit of Eurocentrism and Anglophilia, as I’m preparing for a sabbatical in Durham, United Kingdom. Alan Jacobs’s The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis (Oxford University Press) looks at the relationship between five leading European humanists and their correspondence as Europe and the world burned around them. Could humanism survive such a conflagration, one which it may have helped start?

Fergus Butler-Gallie’s A Field Guide to the English Clergy: A Compendium of Diverse Eccentrics, Pirates, Prelates and Adventurers; All Anglican, Some Even Practising (Oneworld) examines the oddities of English vicars, a theme at least as old as Shakespeare (and likely a good deal older). The Anglican angle is distinctive: vicars were hard to fire, so they could do whatever they liked. Some undoubtedly devoted themselves wholeheartedly to the spiritual flourishing of their parish. Other kinds are detailed in this book: ornithologists and compulsive sleepers and genuinely mentally ill people and at least one vicar who celebrated that no one came to church. (One reason was that he chained the doors shut.) America has not produced the humanist intellects or the oddballs Britain has, for whatever reason. And one reason we read is to see things we can’t see in our own backyard.

Walter Brueggemann: The substantively revised second edition of Richard T. Hughes’s Myths America Lives By: White Supremacy and the Stories That Give Us Meaning (University of Illinois Press) provocatively traces five essential myths that power the American dream. The fresh and stunning thesis is that all of these myths—that we are a chosen nation, nature’s nation, a Christian nation, a millennial nation, and an innocent nation—are designed to support and protect the core myth of white supremacy. Hughes shows how each of these claims is permeated with racist marking. It is a timely gift for any who anticipate an excessively “white Christmas.”

In Miracles: God’s Presence and Power in Creation (Interpretation series, Westminster John Knox), Luke Timothy Johnson offers compelling evidence that the Bible, in both Testaments, is permeated with the miracles of God that constitute core faith for both Jews and Christians. The book provides a comprehensive catalogue of the myriad of miracles that are the unmistakable subject of biblical narratives. The negative counterpoint is Johnson’s contention that the Enlightenment work of Descartes, Hume, and Kant reduced miracles to “violations of natural law,” robbing them of theological authority and significance. The book is an urgent wake-up call to recover the wonder and power of the biblical narrative on its own terms.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Christmas picks.”