The uniquely American story of Crownsville Hospital

Antonia Hylton digs into the history of a Maryland asylum that forced its Black patients to build their own facilities.

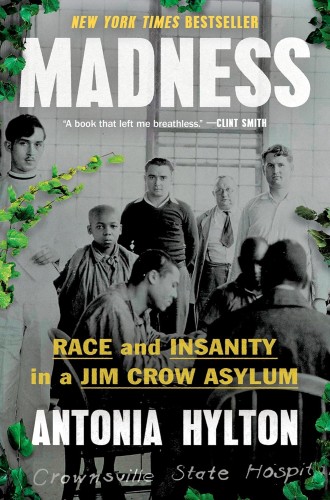

Madness

Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum

I was at a youth soccer tournament when I walked on the grounds of what remains of the Crownsville Hospital for the first time. My youngest was on a team that hosted a tournament on the hospital campus just off I-97, about a 15-minute drive from our home in Annapolis, Maryland. When we drove up to the freshly mowed fields with makeshift bleachers and parked by the decaying Georgian buildings covered in overgrown wild ivy, I felt the hair on my arms raise a little. Briefly Googling some of the history of the hospital confirmed my uneasiness. It was originally named the Hospital for the Negro Insane of Maryland. I wondered about the stories, known and unknown, that lingered in the shadows of the shuttered buildings.

Antonia Hylton gives us a way into those stories, telling the story of the “first and only asylum in the state, and likely the nation, to force its patients to build their own hospital from the ground up.” As Hylton explains, during the First World War, 275 acres of land were developed through the unpaid labor of patients, who not only built a hospital but turned the land into “a modern, highly productive farm—one that was able to produce much of its own food.” These patients were all Black.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

After Emancipation, Maryland lawmakers sanctioned numerous levels of segregation, including barring Black people from assembling for religious events or living in neighborhoods that were more than 50 percent White. By the early 1900s, there was a consensus among doctors that Black people were especially prone to insanity. Something had to be done with all the people who appeared to be mentally battered and bruised, so they were confined to a hospital where physical labor was considered therapeutic. The patient-worker model went on for decades at Crownsville. Because it was the only mental hospital in Maryland that accepted Black patients, it held 2,700 people during its peak years.

Madness is about a hospital, Hylton explains, but it’s also about “American institutional history” more broadly. Crownsville’s “surviving records tell us a uniquely American story” that might “help us understand both our current, broken mental healthcare system and our carceral one.” The deeper Hylton digs into the hospital’s history, the clearer it becomes that our health care and prison systems not only are intertwined but perpetuate each other. Together, they extend an “antebellum social order” that stands against the flourishing of Black people.

Indeed, Crownsville is a kind of microcosm of the region. The conditions for patients were brutal and exploitative, and the hospital’s all-White staff was buttressed by the persistence of racial hierarchy. Alongside accounts of a young Black man lynched on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, Hylton describes the hospital’s practice of isolating and secluding patients. In doing so, she deftly tells a layered story about race—one that doesn’t let us off the hook but makes us look squarely at the suffering of human beings, both at the hospital and outside it.

Although Crownsville sits at the center of the narrative, Madness is also about the lives of particular human beings. To illuminate these lives, Hylton “weaves the testimony of more than forty former patients and employees of Crownsville Hospital with the records that have been preserved at the Maryland State Archives and in the homes of former staff members, and with newspaper reports from both mainstream and historic Black-owned publications.”

Hylton tells the story of Estella and William Jones, who met at the hospital shortly after each began working there. Neither had much education or experience, but “the hospital needed help in every corner.” Despite the terrible pay, the work came with health insurance and potential raises. Bill was hired as a lab assistant and Estella as an aide. By the time they retired in 1996, Bill had assisted in countless autopsies and Estella had worked with generations of children, adults, and families. Their jobs provided economic stability for their family, but they watched in dismay as funding decreased and patients were increasingly discharged with no plan for their care. Perspectives like these illustrate the complex dynamics associated with this controversial institution embedded in the greater Annapolis community.

Madness also asks readers to hold space for the stories of patients. The book opens with a riveting story about William Murray, one of the hospital’s first patients. Murray, a survivor of typhoid fever, suffered from depression. When his wife died unexpectedly, he became a single parent to six young children. Although he was a Howard University graduate, a pianist, and a respected principal and teacher, at the hospital “he was just another inmate.” After several years at Crownsville, Murray got into a disagreement with a guard, who dragged him to the basement and bludgeoned him to death. Of surprising note: he was the father of Pauli Murray, who went on to become an eminent legal scholar, poet, civil rights activist, and Episcopal priest. The last time the young Pauli ever saw her father, in the Crownsville visitors’ room, he was nearly unrecognizable. This experience, writes Hylton, fueled a lifelong “commitment to justice that sprang from a childhood with an intimate understanding of the vulnerable Black American condition.”

Hylton writes about some of her own experiences with family members’ mental health struggles, bringing to life the entangled histories of institutions and communities. This interweaving of stories shows how deeply anti-Blackness is embedded in many of our systems. The book ends on a hopeful note about the county’s endeavor to develop the space for the public by creating a museum of the history of mental health treatment. Crownsville already houses “a food bank and a small handful of organizations treating substance abuse and behavioral disorders.” Madness does not provide easy redemption, but it shows how confronting local histories can lead us to work toward the flourishing of all our neighbors.