The gods present their arguments

David Bentley Hart imagines Eros, Hephaistos, Hermes, and Psyche coming out of retirement to debate contemporary philosophy and science.

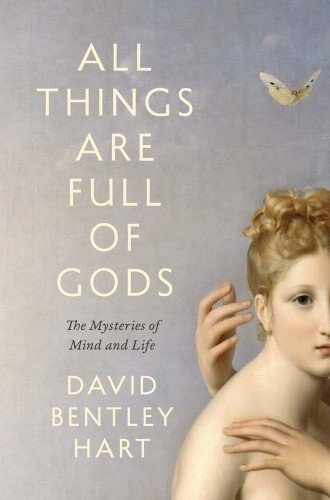

All Things Are Full of Gods

The Mysteries of Mind and Life

David Bentley Hart—an American Goethe who declared a few years ago that fiction writing is his greatest love—would likely prefer to see a review of his Prisms, Veils: A Book of Fables, which was published last year by the University of Notre Dame Press. Philosophy of mind is the main subject of Hart’s most recent book, All Things Are Full of Gods, a literary Platonic dialog between four Greek deities who spend six days in debate over many contemporary philosophy and science topics while reclining on benches amid the vast gardens of the two who are hosting, Eros and Psyche.

The title comes from a Thales of Miletus quote brought up early in the conversations. From comfortable retirements on vast intermundane estates, these Greek deities, although no longer worshiped by us, clearly maintain a keen interest in our story and delight to read up on modern physics, biology, philosophy, computer science, religion, and literature. We first encounter Psyche selecting and plucking a rose after a contemplative search. Her claims about the stages of desire and introspection involved in selecting one rose from such abundance spark an argument with her guest, Hephaistos, over the realities of mind versus matter. They agree on six days of systematic discussion, during which Hephaistos maintains a lonely defense of modern mechanistic materialism against three antagonists, led by the confident yet kindhearted Psyche. Evidently, Psyche—who started life as human before choosing immortality with Eros—is more down-to-earth than her two supporters, the doting Eros and the haughty Hermes.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Psyche despises Cartesian dualism and considers mechanistic materialism as well as most varieties of idealism in the last several centuries to each be idiotic inheritors of only half of this dualism. In place of these three dead contemporary categories of thought, Psyche advocates a more ancient form of idealism that understands the material realm as a substantial manifestation and shared experience of mind and life. This is a holistic and commonsense vision, Psyche claims, that would have been familiar to the ancient schools of Vedantic philosophy as well as Neoplatonists more recently.

With only modest contributions in support of his wife, Eros sounds ready to agree with Dante about “the love that moves the sun and all the other stars.” Hermes holds forth on all topics hermeneutical and defends language as a third eternal reality alongside life and mind. The story ends—500 pages after Psyche selects the rose—with Hephaistos saying that, despite being intellectually and morally unmoved, perhaps he will spend a little less time perfecting his robotics so that he can give some time to gardening.

As one reviewer, C. W. Howell, has already pointed out, a kiss of reconciliation near the end clearly echoes that of Dostoevsky’s Alyosha with his brother Ivan and that given by Christ to the Grand Inquisitor. We might recall that in one version of the myths, Hephaistos is thrown out of his household and off the top of Mount Olympus by his father, Zeus, so that he is left with both legs shattered. He drags himself homeward and labors to design and assemble two female robotic attendants of silver and gold to support him as he learns to walk again. When Hephaistos insists that life is brutal and that we must make what we can out of it by means of anything that science and technology can offer to us, he speaks from experience. Hart, however, does not bring any of this to the surface; he leaves it to rest within the dialogue.

Instead, Hart’s emeritus Olympians work through technical debates citing physicist Paul Davies, biologists James A. Shapiro and Denis Noble, evolutionary biologists Andreas Wagner and Richard Lewontin, geneticist Barbara McClintock, and physiologist J. Scott Turner, among many others. Along with a host of ancient philosophers, Psyche also draws on some contemporary thinkers such as Hans Jonas, Raymond Ruyer, Evan Thompson, and Philip Goff. For his part, Hephaistos turns—in perhaps his most substantial last stand—to neuroscientist and psychiatrist Giulio Tononi’s integrated information theory. All of these voices are critiqued from both directions by the lineup of dueling deities, although mechanistic materialism is dramatically underrepresented.

In the debate’s first several days, the topics are largely metaphysical, and many readers will find themselves in unfamiliar and perhaps alienating or dogmatic-sounding territory. Bold and blunt assertions of sheer logic shut down conversation. However, in the final days of discussion, as the topics turn to quantum physics, evolutionary biology, and computer science, readers will easily find points of contact. For example, Psyche argues that we have inverted the true relationships between the natural sciences—that biology, as the science of life, should be the most fundamental science instead of physics. This reversal of conceptual frameworks, she contends, would allow us to understand physics more fully as participatory in life and mind.

Amid all of our contemporary complaints of reduced attention spans and media fatigue, Hart expects a lot of his readers. His dialog lasts longer than a game of cricket, and the conversationalists sound like members of a garden party in an episode of The Crown. However, the range of topics, the boldness of the vision, and the relational dynamics between characters will sustain the persistent reader. For those seeking help in advance, Hart’s 2013 book The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss is a more manageable version of some key early points developed in All Things Are Full of Gods.

By the second half of this new book, however, Hart moves into topics on which he has not written before. He

gives in-depth consideration to neo-Darwinism, information theory, and several other big-picture topics related to our existence within the chain of being. As with The Experience of God, Hart is making a very different kind of case for God than what we see from most of today’s prominent apologists. Their interests in God’s capacities as an engineer and a fine-tuner of possible worlds stand in contrast to Hart’s Alpha and Omega, who is neither architect nor artisan.

As another helpful entry point, potentially, we have an origin story for the book shared several years earlier. In Roland in Moonlight, an autobiographical fairy tale published in 2021 by Angelico Press, Hart receives substantial help in his initial concepts for this book from his dog, Roland. The research behind All Things Are Full of Gods is funded by a Notre Dame University fellowship secured through a proposal written and submitted by Roland, who worried that Hart seemed unlikely to complete the process due to a health crisis precipitating “habits of despair, anger, and insomnia.” While fetching a cup of tea in the predawn hours one morning, Hart finds that “unexpectedly—though, perhaps, in another sense quite predictably—I received assistance from someone who understood my project as well as, or perhaps better than, I did myself.” Roland has written and submitted the proposal.

Hart has some initial concerns: “You have some fairly exotic ideas. I mean, you’ve confessed to being something of a panpsychist, after all, and . . .” But Roland brushes these fears aside and encourages Hart to read through the proposal, which Hart finds is, indeed, fully to his own satisfaction. This full proposal is published within Roland in Moonlight and makes another helpful piece of background for those undertaking the pilgrimage of Hart’s newest book.

The thought of Sergei Bulgakov (whom Hart has called “the greatest systematic theologian of the twentieth century”) also resonates with the concepts in All Things Are Full of Gods. While Bulgakov is not named in the book, themes such as these from The Bride of the Lamb provide many points of contact with Psyche’s case: “Nature is revealed in multiple individuals, but it is not divided.” Rather, it “is inwardly transparent and has a single destiny” that “is most accessible in its biological aspect as heredity, the organic connectedness of the human race, and in its sociological aspect as the gregarious character of the human race, manifested in economic, legal, governmental, cultural, and linguistic connectedness.”

All Things Are Full of Gods engages a host of philosophical and religious traditions, and Hart’s own convictions as a Christian do not rest below the surface. Topics related to Christian faith and theology arise as the four deities cover long stretches of intellectual history. Hephaistos asks in frustration, near the end, if the others have any plans to be baptized. Eros replies, “I don’t think superannuated gods are typically invited to participate in ‘the mysteries’” and clarifies that he will “let bygones be bygones.” Referencing the traditional last words of Julian the Apostate (“You have conquered, O Galilean”) as if this must simply be taken for granted, Eros returns to making his point about an insight taken from Maurice Blondel.

Despite the humor of such passages (and because of them to some real degree), the book is not polemical. Its underdog god remains heroically and sympathetically undaunted in his adherence to mechanistic materialism. As Hephaistos puts it on day six, he and Psyche “may not be able to agree on matters metaphysical,” but they know that they “both love the tormented, beautiful world we left behind when we came here” so that “at least our hearts are in accord, if not our beliefs.” With this book, we now have Psyche and Hephaistos joining the ranks of Roland and Hart’s fictional great-uncle Aloysius Bentley to bring us a vision of reality that no one voice or person could convey.