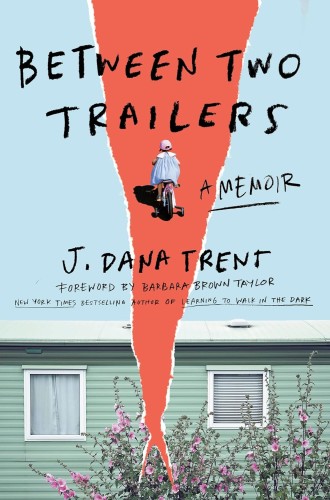

A different kind of poverty memoir

Dana Trent’s heartbreaking and hilarious book eschews the conventional American rags-to-riches arc.

Between Two Trailers

A Memoir

“My father was born in Vermillion County. He was the kind of wanderer who knew the value of home. No matter what any stranger or pundit said, to him Indiana was a magical place full of good buddies,” writes J. Dana Trent in her memoir, Between Two Trailers. Witty, poignant, and unrelentingly honest, this coming-of-age story traces a woman’s journey from preschooler who assists her drug-dealing father to ordained Baptist minister and college professor. In a story simultaneously heartbreaking and hilarious, Trent shows us that no matter how painful our origins, there is healing to be found when we dare to go back home.

The last several years have seen a proliferation of memoirs exploring poverty in the United States from the perspective of individuals who overcome it. J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, Tara Westover’s Educated, and Stephanie Land’s Maid all involve characters who overcame childhood adversity to start prosperous new lives as adults. What distinguishes Trent’s memoir from these and others in the coming-of-age genre is its refusal to employ the conventional American rags-to-riches plot arc. Trent’s story has neither heroes nor villains, and it ends not with a “happily ever after” or fully transformed life but rather with the narrator’s poignant reconciliation with her upbringing.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

Trent’s father, “King,” is a former recreational therapist, college-educated, who suffers from schizophrenia. Her mother, “the Lady,” is a nurse who suffers from personality disorders that keep her stuck in unhealthy patterns. Both are portrayed vividly and with deep love. The same King who trains a young Trent (“Budgie”) to be a lookout during his drug drops uses picturesque midnight bike rides around the county to teach her about her family’s history. The same mother who steals her daughter away to start a new life in North Carolina and racks up thousands of dollars in debt also encourages her to go to Duke Divinity School.

And yet, this is no Cinderella story. Upon reaching adulthood and graduating from Duke, the narrator works modest jobs: first as a hospice chaplain, later as a secretary, and ultimately as a community college professor. She continues living with her mother through her late 20s. She struggles with alcoholism and obesity. While many people—from aunts and uncles to a sympathetic college French professor to some college classmates who become lifelong friends—offer help and support to Trent, no knight in shining armor comes to save her. She falls out with once beloved friends and becomes estranged from her father for a time, an estrangement that ultimately leaves her with one of her deepest regrets.

Before Trent published her memoir, she told her story in a podcast called Breaking Good. In addition to referencing the acclaimed TV drama about a chemistry teacher turned drug lord, the podcast title suggests decision-making and action. Overcoming adversity and changing one’s life for the better is not a linear process; it is something Trent must strive toward again and again throughout her life.

For a middle-class reader like me, this memoir challenges many common prejudices about people who live in poverty. Both of Trent’s parents are college educated and, at the beginning, gainfully employed. A mixture of bad luck and bad choices influenced by severe mental illness lead them to inflict pain on their daughter, turning her into “a parental child who longed to take care of King and the Lady.” From Trent’s earliest childhood, they continually place their needs above her own.

Behind the harrowing plot lies the narrator’s deep respect for earnest people who lack economic opportunity and the structural support needed to treat addictions and mental illnesses. Trent describes her hometown and namesake, Dana, Indiana, as a community that was once prosperous:

A thriving railroad and a large grain elevator made the town a booming agricultural hub. People worked the fields and loaded railway cars to feed the nation. Civil War–era homes in pristine condition housed families with a basketball team’s worth of kids. My grandfather owned the town’s busiest grocery store. An opera house, a theater, a broom factory, a laundromat, a bank, a garage, and churches all kept 1950s residents busy and faithful.

“But prosperity is always temporary,” continues Trent. “The glory days were gone. . . . Caved roofs, broken windows, and vicious unleashed dogs anchored my own childhood.”

In a country ravaged by poverty and addiction, this picture of a crumbling small town is surely familiar to many. For Trent, small towns such as these are the backbone of US society. When, after a long time away, she returns to the annual Ernie Pyle Firemen’s Festival in her county (named for the celebrated World War II journalist), she describes her hometown as “full of good corn folks who care about one another,” who serve homemade noodles with “green beans so tender they broke apart on your fork. Men I’d known almost since birth had stirred those beans outside the Dana firehouse since daybreak, toiling over cauldrons to ensure the entire community could eat.”

The power of this memoir is the way it blends tragedy and comedy. In classic Shakespearean drama, tragedies end in death, signaling the destruction of a community, while comedies end in weddings, signaling the persistence of a community toward an imagined future. Many of Shakespeare’s late plays combine both tragic and comic elements, weaving a complex tapestry of human experience, showing life in all its messiness. Similarly, Trent’s memoir ends with both immeasurable grief at the deaths of her parents and the deep joy expressed in weddings—her own and that of a young couple her whole hometown gathers to celebrate. Between Two Trailers is a true Indiana Hoosier tragicomedy.

“Wounds and blessings come in matched pairs, at least if we’re willing to wrestle them to the ground,” states Barbara Brown Taylor in her foreword to the book. Throughout the memoir, Trent consistently sees the world in all its complexity, from the comfort of her grandparents’ Chef Boyardee meals to the callousness of some of her college classmates to the tremendous resilience her parents show throughout their lives. For Trent, the redemption that the Christian faith promises is not a onetime event. It is a clumsy, stumbling, beautiful journey toward home.