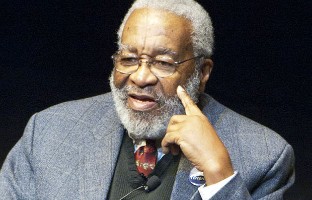

Vincent Harding, a true hero

It is a special kind of sadness that lingers when a hero dies. We remember long afterward the way in which we heard the news. In the days following we find companionship in others who feel the way we do, as we recall the lessons we learned from the person who inspired us.

That kind of sadness has accompanied me since yesterday evening when one of my heroes, Vincent Harding, 82, a scholar and “veteran of hope,” went home to be with God. I lit a candle and gave thanks for this great man who had shared clear vision, bright passion, and inviting warmth.

I was honored to meet Harding years ago when I served on a panel with him and his wife and fellow worker for freedom, Rosemarie Freeney Harding, who died in 2004. (The subject was activism through the generations; I was 17.)