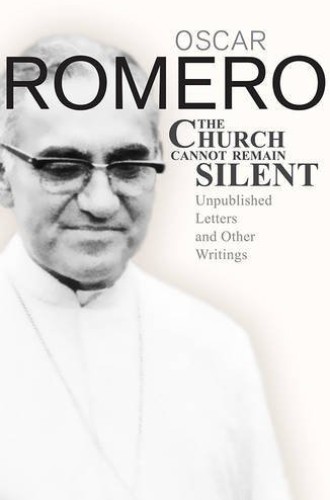

Oscar Romero's wisdom for today

The Salvadoran archbishop was thoroughly of his own time. But his words speak to us too.

“We experience here great contrasts in the life of our society, in economic, political, and cultural marginalization,” Oscar Romero wrote in a letter on February 9, 1978. “In a word, INJUSTICE. The church cannot remain silent in the face of such misery, for to do so would be to betray the gospel, it would be to become complicit with those who here trample human rights.” It’s tempting to apply his prophetic words to our own context, in which increasing economic, political, and cultural contrasts have produced a renewed sense of urgency for many.

But we are far from Romero’s situation. As archbishop of San Salvador in the late 1970s, he was surrounded by instances of torture, disappearances, false imprisonments, and assassinations. He knew priests and nuns who were brutally and unapologetically killed, and Romero would eventually be murdered while presiding at mass. As he wrote the letters and sermons excerpted in this book, the violent repression of political dissent in his city (and across his country) was driving refugees to flee, looking for asylum. Romero explains:

There is no freedom of expression; if someone asks for a piece of bread, he’s thrown in jail. It’s forbidden to say that people are dying of hunger and malnutrition, that they have no health care, that the unemployment rate is very high (65 percent in our country), and that illiteracy is a serious problem.