The new illuminated manuscript?

When I learned that white evangelical women are drawing and painting all over their Bibles, I was caught between judging and celebrating the phenomenon.

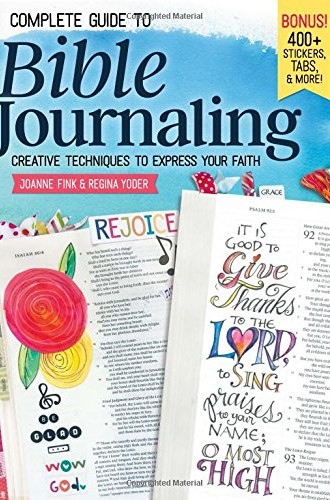

I really wanted to dislike this book when I first heard about it. It’s a technique book on Bible journaling with a yellow flag on the cover boasting “Bonus! 400+ stickers, tabs, & more!” The thought of people coloring and stickering the pages of their Bibles (and a publisher capitalizing on that trend) vaguely worried me as I recalled Revelation 22:18. Further, I was annoyed by the fact that the contributors to this book are all women—as if the creative arts are delegated to the realm of womanly things in the white evangelical Christian world, where this book is solidly rooted.

But the book’s increasing popularity over the seven weeks since its release convinced me to take a closer look. Complete Guide to Bible Journaling is a #1 best-seller in several categories on Amazon, including “Ritual Religious Practices,” and “Christian Rites & Ceremonies.” Even more astoundingly, it’s currently ranked at #1034 in books: of all the books, in every genre, that are sold through Amazon, only 1033 of them are selling more copies than this one! By way of comparison, Reinhold Niebuhr’s The Nature and Destiny of Man is currently at #62,252, and the Penguin edition of Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling is at #11,849. (To be fair to Niebuhr and Kierkegaard, their books aren’t new releases—Amazon shoppers have already had plenty of years to get these volumes on their shelves.) But Complete Guide to Bible Journaling even outpaces Michael Eric Dyson’s Tears We Cannot Stop, which is currently ranked at #1670.

As I dug into the phenomenon of Bible journaling, I was surprised to learn how widespread it is. Journaling Bibles are available in a variety of versions—KJV, NIV, and ESV seem to be the most commonly available—and with various sizes of margins (or even blank interleaved pages) to allow for writing and drawing. That’s where this book comes in: it is, as the cover claims, a resource book aimed at inspiring and encouraging Bible-journaling Christians to engage with scripture in new, creative ways.