To name or not to name

The Holocaust was perpetrated against specific groups of people. Is this fact a crucial part of every retelling?

The controversy that erupted after President Trump gave an International Holocaust Remembrance Day speech that failed to mention Jews was overshadowed by furor over the executive order he issued the same day. While the order—which suspended entry into the U.S. by people from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen—didn’t name Muslims as the targeted group, it was clearly aimed at Muslims. Whether it is officially judged as discriminatory against Muslims is now in the hands of the court system.

The lesson in both cases seems to be this: it’s easier to get away with discriminating against people if you don’t name the group against which you’re discriminating. When we remember acts of systemic violence or genocide from the past, the value of naming the people who were targeted isn’t just sentimental or symbolic. It’s confessional. Articulating the details of past sins forces us to turn inward and examine our own complicity rather than blame only others. It’s also performative. Saying the names of targeted groups aloud is an act of resistance against the evil that resides within our history and still churns under the surface threatening to re-emerge.

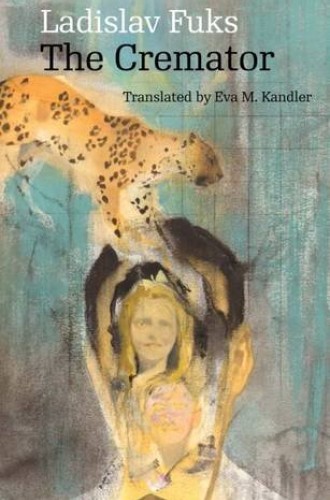

Ladislav Fuks’ novel The Cremator, published in 1967 and first translated into English in 1984, also demonstrates this point. The protagonist, Karel Kopfrkingl, lives in Prague with his family and works at a crematorium as Hitler’s troops invade Czechoslovakia. Kopfrkingl is a bit entitled, as well as naïve and morally flimsy. But initially he resists his friend Willi Reinke’s harsh language about who is the real enemy in the war. Willi speaks about “inferior weaklings,” “parasites and insects,” “those who are responsible for our poverty,” and “a wretched people who don’t understand anything.”