My five-year-old, whose booster seat in the car provides her a clear view of the driver, is more fastidious than a driver’s education teacher. “HANDS ON!” she yells anxiously whenever I take a hand off the wheel momentarily. (No matter if I’ve removed the hand in order to hand her the snack she’s requested or take the dirty tissue she is thrusting my way. Apparently, mothers who drive are expected to meet their children’s every need while also keeping both hands on the wheel at all times.)

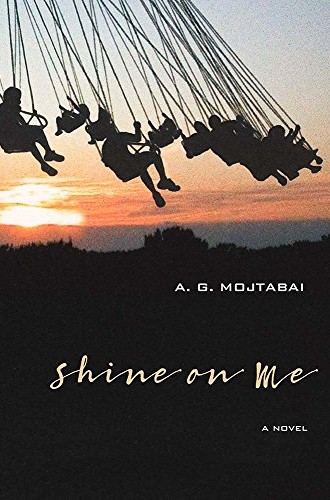

But I understand the impulse behind my daughter’s exhortations. There’s security in holding on to the things that we think will keep us steady or safe. Or, in the case of A. G. Mojtabai’s new novel, holding on to the things that we most desire. The novel revolves around an event that happened years ago and was later documented in a film and portrayed in a Tony-nominated Broadway musical: a contest sponsored by a Texas car dealer in which the person who keeps his or her hand on a new truck the longest gets to keep it. The book is focused primarily on the tedious hours during the latter portion of the contest, but Mojtabai’s rich portrayals of her characters’ inner lives through sparse prose build an intriguing narrative that deepens as the plot unfolds.

This book, at its heart, is about people: what drives them, what haunts them, what sabotages them, what propels them to success. As the hours turn into days and fatigue sets in, reality slips further from both contestants and observers. They use the bathroom breaks to psych one another out over cigarettes. They taunt one another, discovering and exploiting each other’s psychological weaknesses. They attempt to trick one another into removing their hands from the truck. For each of them, the fears and failures of the past merge with the present, shaping what it means to stand under a tent beneath the broad Texas sky with strangers competing over a common goal.