See the asylum seekers’ wounds and believe

At the border, survivors of violence present their scarred bodies as testimony.

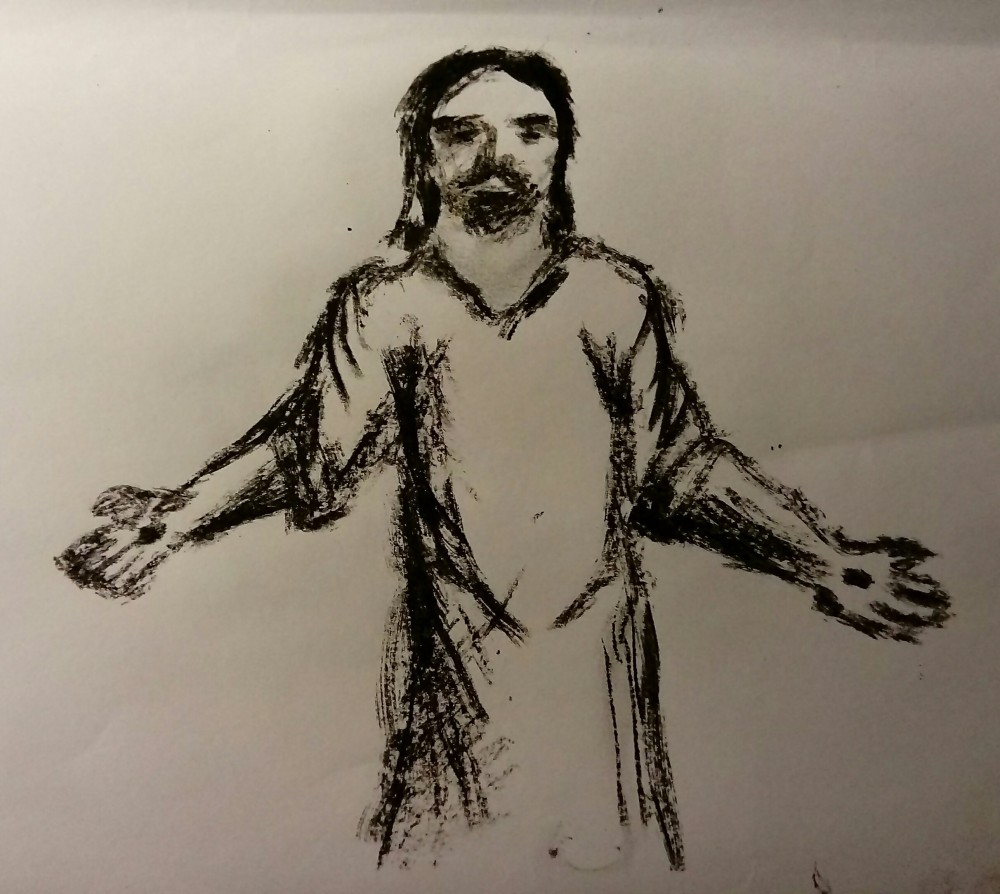

Unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side, I will not believe.

These Easter words from John’s Gospel bring to mind my experiences on a recent trip to our border at San Diego and Tijuana near the San Isidro port of entry, the busiest border crossing between the United States and Mexico. The asylum seekers who wait to present themselves there will face what’s called “a credible fear interview.” They will try to convince people who are not likely to believe them that their life is in danger and it is not safe for them to return to their country of origin.

Although immigrants are repeatedly labeled as criminals, my experience with dozens of parents and children arriving at our border is that they are far more likely to be the survivors of violent crimes. Lacking police reports or other supporting evidence, asylum seekers are hoping to offer their scarred bodies as testimony.