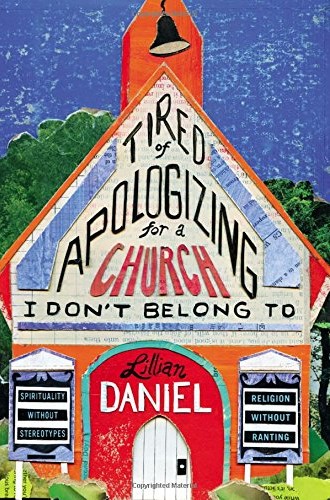

Good church, bad church

When our evangelism focuses on apologies instead of God’s grace, we're burying the lede.

Lillian Daniel compellingly argues that that the church would be better off if we were to proclaim and enact the good news of God’s generosity rather than apologize for the errors Christians continually make. When we approach evangelism from an apologetic stance (as in: “I’m sorry those three churches you experienced seventeen years ago didn’t meet your needs. And before you even raise it, let me apologize for the Crusades, the Inquisition, suicide cults, and any other stereotype that kept you from looking further”) we diminish the value both of our conversation partner and of our community of faith. “In my apologizing days,” she explains, “people often came around to liking the version of church I was describing. But looking back, I can see it was a conversation of critical distance in which both parties kept God at arm’s length. I was apologizing for a sport while selling them on a team.” She was so busy extolling her own open-minded view of God that she didn’t have time to talk about how she experiences God. She was burying the lede.

The lede isn’t crankiness, ranting, apologies, or stereotypes. It’s grace, experienced in community and filtered through humility and humor. Daniel, who excels in theological storytelling, captures that grace best when she exposes her own vulnerabilities.

Describing a conversation with a pew-mate who had caught her looking bored during an evangelical worship service for gay Christians, Daniel confesses: “it was like she had read my evil and limited mind.” Daniel hadn’t been judging the worshipers simply because their worship style didn’t match hers. She knew they were searching for a place to feel at home, a church that would welcome them without trying to change their sexual orientation. So she wondered: “Why didn’t they just dump all this oppressive stuff and come to my church instead? We’ll do your gay wedding and spare you these blood songs with rainbow slides. It was a win-win. What did they have to lose?” But then her pew-mate pointed out that praise songs and PowerPoint presentations constitute meaningful worship for many people. “Her words reminded me that . . . it was arrogant and simpleminded of me to assume they all wanted just to jump on board my little ship.”